RIBA’s new exhibition looks at how architects have rebuilt cities destroyed by natural disasters

Nobody knows how many people died in the fire. Six deaths were recorded, but many were thought to have been incinerated beyond recognition and many more cooked alive in temperatures exceeding 1,700 degrees Celsius.

The streets resembled the lower circles of hell and the Great Fire, as it became known, was the second tragedy to have struck the City of London in a year. Before, it was The Great Plague that had driven Londoners from their homes, but this latest assault had almost wiped out the rest; it had destroyed 13,300 homes, swallowed up most of the City’s public buildings, and consumed 85 churches including St Paul’s Cathedral.

In 1666, London was on the endangered list. But its inhabitants hadn’t given up hope. Schemes poured in to the King, from bona fide architects to overly-ambitious citizens. Five were taken seriously, from John Evelyn, Robert Hooke, Valentine Knight, Richard Newcourt and Christopher Wren, and they form the starting point, not just for a new exhibition at the Royal Institute of British Architects, but for a new kind of architecture.

When cities are devastated by natural or – in the case of the Great Fire of London – man-made disasters, it often signals a turning point, a moment of reflection, a once-in-a-century opportunity to rebuild for the better.

“Creation from Catastrophe: How Architecture Rebuilds Communities” is the first time that centuries of efforts from all over the world have been gathered in one space, their stories told using original models, sketches, short films and photographs at RIBA’s headquarters in Fitzrovia.

The five original masterplans for London differ wildly from the meandering city we live in. In fact, anyone studying a map of London can only conclude that there was no plan and the city just evolved organically, for who would design such a convoluted mess?

Then again, some of the plans go too far the other way. Richard Newcourt’s, for example, is eerily repetitive; a perfect square containing rows of more squares, each containing a church and four streets leading north, south, east and west. There’s little acknowledgement of trading routes or shipping ports, merely the suggestion that God is all the city needs to survive.

However, it was Valentine Knight’s plan that was the least well received; the army captain volunteered a network of 24 streets running east to west, and 12 streets running north to south, similar to Manhattan’s grid. But it was the creation of a new canal that really ensured his scheme went up in flames. He suggested visitors pay a toll to fund the reconstruction of the City, and King Charles II was so offended by the intimation that he might “draw a benefit to himself, from so publick a Calamity of his people” that he ordered Knight’s immediate arrest.

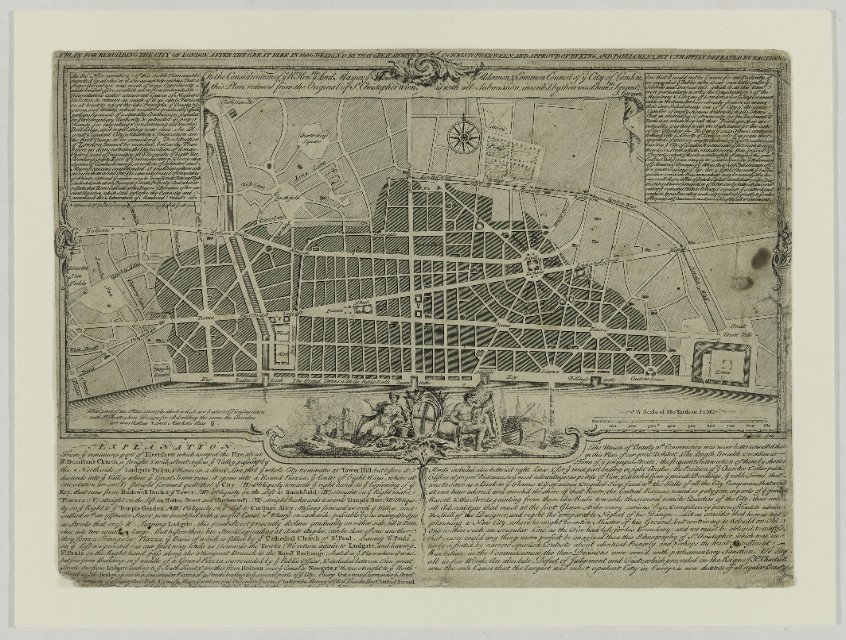

Christopher Wren's masterplan following the Great Fire of London in 1666

Christopher Wren's masterplan following the Great Fire of London in 1666

In this light, Sir Christopher Wren’s vision may as well have been gifted by the Gods, and if all had turned out according to plan – quite literally – London would have been a baroque masterpiece to rival Paris or Rome. In Parentalia, a family memoir also available to read in the exhibition, Wren saw that “The Fire of London furnished the most perfect occasion… to be rebuilt with Pomp and Regularity.”

Wren wanted to replace its narrow streets with wide avenues radiating from piazzas lined with grand townhouses. But a lack of finances and complex land ownership issues got in the way, meaning only 52 churches were rebuilt, including St Paul’s, around which most of Wren’s surviving streets are located. When the opportunity arose for a revolution, Britain once again opted to ignore it, instead waiting for an orderly queue of architects to form before tying itself in knots with red tape.

While Wren’s London didn’t turn out to be quite the revival he’d had in mind, it was a classic example of top-down city planning, where a masterplan is imposed on a city from on high, rather than decided by those living there. Nearly a century passed before another city was presented with a similar choice. This time, it was Lisbon; the city and its provinces were almost completely destroyed by an earthquake and subsequent tsunami in 1755 that was so large, its effects were felt across Southern Spain, North Africa and even the Caribbean. Sixty thousand people were killed and the city was devastated. King Joseph I, however, chose to wipe the slate clean, and it led to a huge breakthrough in architecture: the Pombalino cage, which was the earliest earthquake-proof construction in Europe.

XLE's plans for floating communities in Lagos, Nigeria

XLE's plans for floating communities in Lagos, Nigeria

Thankfully, we don’t have cause to appreciate this marvel in Britain, but we are surrounded by the fruits of another disaster, particularly in the City: the skyscraper. Chicago fell prey to an enormous inferno of its own in 1871, which left more than 100,000 of its residents homeless.

This paved the way for the “Chicago School” of architecture to emerge, led by the likes of William Le Baron Jenney and Louis Sullivan, and it was characterised by high rise commercial buildings with big, glass windows, held aloft by fireproof metal frames. Also inspired by the great European cities, architect and city planner Daniel Burnham produced a masterplan that resembled L’Etoile of Paris, with parks and civic buildings in the centre and avenues running diagonally off them. Though this cityscape was never fully realised, the Burnham Plan, as it became known, became hugely influential in city planning.

Fast forward a couple of centuries, and our natural disasters are beginning to take on a different flavour. With rising sea levels caused by climate change, the oceans are our biggest threat and, argues Henk Ovink, Special Envoy for International Water Affairs for the Netherlands, this top-down approach to city planning will no longer suffice.

“Water is the number one global risk in the next decade,” he says, “About 90 per cent of all disasters are already water-related, so why don’t we understand it better?”

Critics of the top-down approach say that these ambitious masterplans rarely work, that the victims of natural disasters are too busy with day-to-day survival to delay a return to normality in favour of a radical reinvention that may benefit them in the longer term. But this is precisely what we are seeing in the 21st century; rather than building defences against nature, citizens are taking part in consultations to work out how to live with it instead.

The city of Constitucion in Chile, for example, is constantly dealing with the after-effects of earthquakes and tsunamis. After an assault by both in 2010, local architectural firm Elemental proposed three options; to leave the destroyed land fallow; to build a protective wall between the estuary and the city; or to turn the most vulnerable part of the city, La Poza, into a sustainable forest to act as a buffer against future tsunamis. Then architects built an “open house” in the main square so that citizens could stroll in and learn about their plans. The locals voted for the third option, which meant over 100 families had to relocate to secure the future of their city.

Housing built for victims of the Nepal earthquake in 2015

Housing built for victims of the Nepal earthquake in 2015

In other parts of the world, too, citizens are choosing to change the way they live rather than rebuilding. When a fifth of Pakistan was flooded in 2010, architect Yasmeen Lari worked with local students to train people to build their own bamboo homes, which didn’t rely on outside supplies and were more resilient to natural disaster. Erosion, deforestation and subsidence mean flooding and storm surges are also becoming a recurring problem in Lagos and Port Harcourt. In 2012, 30 of Nigeria’s 36 states were flooded, prompting local practice NLE to develop two ecological buildings, Makoko Floating School and Chicoco Radio, to deal with varying sea levels and pioneer waterfront developments.

In addition to his International Water duties, Ovink also worked with Dutch architectural firm OMA to re-shape Hoboken, New Jersey, after 80 per cent of it was submerged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 (the practice won a competition for the work called Rebuild by Design). OMA’s grand plan for Hoboken was to build a greenbelt of parkland to soak up excess water and transform its parks into water-containment basins, providing “a sustainable path to living with water”.

Ovink says places like Hoboken have a lot to learn from the Dutch; as one of the flattest nations on earth, with 25 per cent of its land at or below sea level, they’ve been learning to live with water for centuries. “The Netherlands is a weird place,” he says. “If we had done a cost-benefit analysis when we’d settled there, we all would have moved to Germany or France. But, of course, no one does; that’s just not the way things work.”

Now, says Ovink, is the time to use our knowledge proactively. “Knowing that crises are increasing in impact and frequency, we are having to create before a catastrophe, using the process we’ve traditionally used after the fact.”

Low-lying deltas are thought to be home to around half of the world’s population and much of its wealth, and they are most at threat from climate change. Looking back on how the great cities of the world have reinvented themselves in the aftermath of disasters doesn’t just instil a sense of hope: it’s vital to protecting our future.

Creation from Catastrophe: How Architecture Rebuilds Communities is free to view at The Architecture Gallery, RIBA, until 24 April.