Rethinking the safe haven: What’s fuelling gold’s rise

Simple assumptions about the yellow metal could result in traders getting burnt. Treasury yields could be a better metric for gauging where it may go next

To many, gold’s sharp rise in recent months, widely attributed to increasing geopolitical tension in Ukraine and fears of a Chinese economic slowdown, has underscored its role as the pre-eminent safe haven asset. After losing 28 per cent of its value in 2013, falling to levels close to $1,200 per troy ounce at the end of the year, the yellow metal has since gained around 15 per cent, reaching a six-month high of $1,392 on Friday, before paring back slightly yesterday.

But others are calling the safe haven story an oversimplification. Since the start of gold’s protracted descent last year, a number of investors (George Soros among them) have called into question the metal’s status as a safe haven asset. Its fall in the first half of 2013 failed to provide much of a hedge against eruptions of market instability in Cyprus, for example. And Adrian Ash of BullionVault cautions against interpreting even the recent price spike as a reaction to the crisis in Ukraine. There are many moving parts to a full analysis of gold’s price fluctuations. Anyone who interprets it as a straightforward play on risk sentiment is in danger of being burnt.

FLIGHT TO SAFETY

Gold plays a fairly unique role in the financial world. Paying no income, and with only minimal industrial utility, it has long been regarded as an effective hedge against economic disaster scenarios – hyperinflation, war, or stock market collapse. And this safe haven status, according to Julian Jessop of Capital Economics, in large part explains the metal’s rebound this year.

“I’m surprised there’s a debate over this,” he says. “The test of a safe haven asset comes in bad times, not good, and gold has passed this test recently in relation to the Ukraine crisis.” Jessop argues that gold’s collapse in price last year does not in itself represent a breakdown of the relationship with risk appetite. Risk assets, including equities, largely soared in 2013, and the lack of a large safe haven reaction to mini crises like in Cyprus can be explained by specific circumstances – central banks were threatening to release portions of their gold reserves at the time, potentially flooding the market, while investors were still digesting the Federal Reserve’s first hints at the tapering of its enormous bond-buying programme.

And gold is not the only traditional safe haven asset to react to the recent events in Ukraine. Dollar-yen closed at ¥101.34 on Friday, marking the yen’s fifth straight day of gains (a trend that reversed yesterday). Yields on US 10-year bonds, meanwhile, fell from 2.76 per cent in the middle of February to a low of 2.6 per cent last week, suggesting increased demand.

COMPLEX DYNAMICS

But the Cyprus example demonstrates a fatal flaw in conceiving of gold’s price movements as primarily a matter of haven demand in times of panic. As Frances Hudson of Standard Life Investments says, “there are so many moving parts to this. Is gold a safe haven in all cases? Absolutely not.” Central bank policy, for example, can complicate the analysis (as it did in the case of Cyprus), and Barclays commodities analysts recently argued that the prevailing trend towards monetary normalisation in the West will be a significant headwind for gold in the coming months (with the Fed seemingly on auto-pilot in its $10bn a month wind down of quantitative easing).

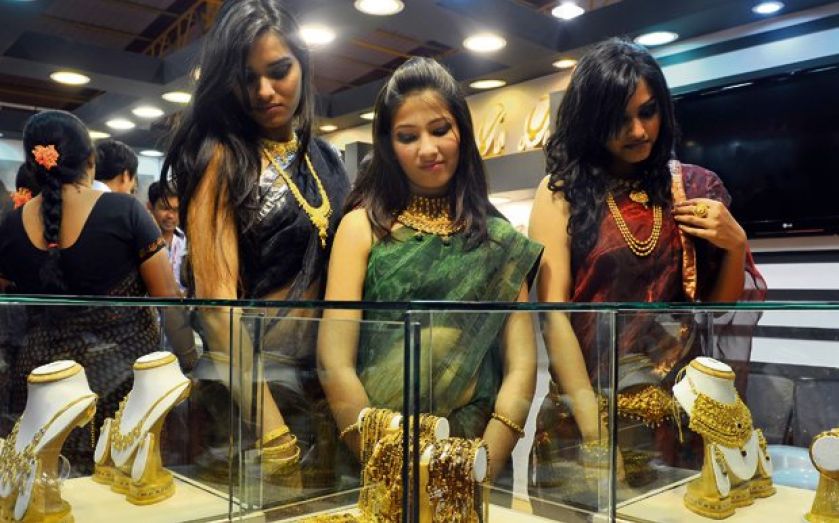

Ashraf Laidi of City Index, meanwhile, says that the Ukraine crisis has not been the only factor moving gold. “Central bank buying has been a notable force, as reserve managers entered the market close to the $1,180 level.” While a loosening of physical gold import restrictions in India and a weaker dollar (which last week marked its fourth consecutive weekly fall against a basket of currencies) have also helped.

In fact, as Ash points out, net long positions on the metal actually started to pick up just before the turn of the year (before the Ukraine crisis seriously erupted, see bottom left chart). “Gold is rarely moved by geopolitical events,” he says. “When it is, that means we’re in heaps of trouble. Iraq, Bosnia, Serbia, Iraq again – none of those major conflicts moved the needle in physical gold.” Ash argues that a far more salient metric to watch for the future of gold will be Treasury yields (which ticked up slightly yesterday), which he says remain depressed because US base rate rises are still some way off. “Even with tapering underway, the stance is still very accommodative.”

NO SAFE HAVEN FOR ALL SEASONS

So why does all this matter? A correct diagnosis of past price movements could give a better guide to future dynamics. If Ash and others are right that gold is not always a straightforward “risk-off” move associated with global tensions, then a knee-jerk flight to the metal in reaction to future flare-ups could prove misguided. A BlackRock analysis looked back at the best-performing assets in times of “high stress” in 2013, and found that gold was the worst performer relative to the All-Country World Index on a risk-adjusted basis, with 10-year Treasuries performing best on this measure (see bottom right chart).

UBS analysts argued in a note released last May (Rethinking Safe Haven Investments) that the “demand function for gold is more complex than any other commodity”, and its caricature as a safe haven could be revised as a result. To reinterpret a famous phrase, all happy markets are alike, but each crisis unfolds in its own unique way – and gold will not necessarily provide adequate protection in all cases.