Rent controls will only help those already in homes and hobble everyone else

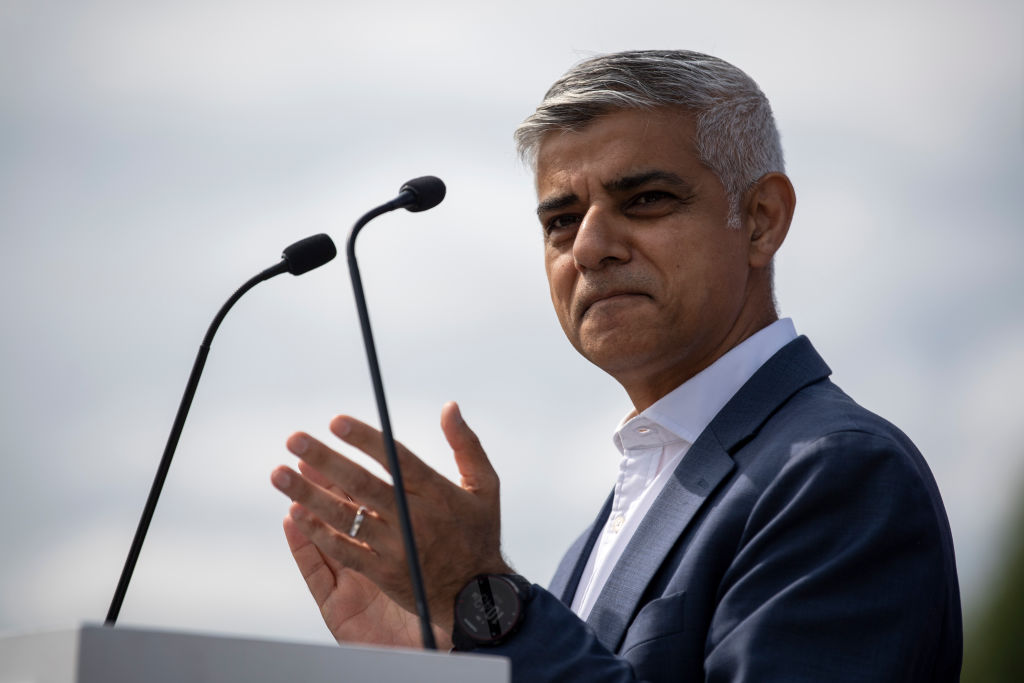

Sadiq Khan thinks rent controls are a great idea for London. They’re not: they would reduce investment and therefore supply in a private rented sector that’s already struggling, writes Ian Fletcher

Over the past year there has been a surge of calls for rent controls in the private rented sector. It is understandable, household budgets are being hit by a cost-of-living crisis. A mismatch of supply and demand for rental property, not helped by either policy, or the pandemic, has also put pressure on rents.

Rent controls are seen as a “golden ticket” by a few politicians – a cost-free and populist way to put money into voters’ pockets, and at no cost to the state. This explains some of the loose statistics that politicians bandy around. Sadiq Khan for example, has quoted rents rising at 16 per cent. A day later, his City Hall statistical unit referred to official national statistics of 4 per cent in London, and 4.2 per cent annual growth in the rest of England.

The former stat probably came from advertised new lets, from one of the property portals. The lower actual number reflects rents within existing tenancies, as well as new lets. And therein lies one of the great contradictions of rent controls. Those who benefit from rent controls are those already in their homes, whose owners will tend to moderate their rents anyway, because the benefit of keeping a good tenant far outweighs the cost of reletting.

Rent controls do nothing for those desperate to get a first foot on the housing ladder. The private rented sector has housed more people in the past decade than the state-funded affordable sector has with subsidies in short supply.

The private rented sector is under significant strain though. Fewer properties are coming forward. Nationally there were 29 per cent fewer portal listings in the third quarter of 2022 versus the 2017-19 average. Since 2019, there have been close to 182,000 buy-to-let loan redemptions. Smaller property owners left the market just as pent-up demand from the pandemic exploded. As a result, it’s taking about half the time it normally would to let a home.

Rent controls will only make this situation worse. Putting a cap on rents impacts investment and reduces rental housing supply. It favours tenants on higher incomes with stable employment at the expense of those on lower incomes and families and reduces funding available for property maintenance. In the long term, it can create a long shadow on the rental market with lower quality homes.

Perhaps the most prescient argument against rent controls is that they deprive more people of homes. Of course, if the state was to fund a large expansion of social housing that might provide the counterweight to a shrinking private rented sector, but in my lifetime I have yet to meet a politician that is willing to put up taxes to fund a large expansion of social housing.

At a time when the private rented sector is bursting at the seams, to introduce rent controls and further reduce investment and therefore supply in the private rented sector would be utter folly.

It also opens up the nightmare scenario of politicians getting into a bidding war over rent controls, with rents driven to a level that bears no relationship to what is sufficient for investors to make a return or what it costs to fund the upkeep of private rented sector properties. One person advocates 3 per cent rent rises, another 2 per cent, and then another 1 per cent. It’s not hard to imagine.

The shelves of academia are littered with evidence showing the damaging impact of rent controls in places as diverse as New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Berlin, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, and so on. Fundamentally, while rent control may be seen as a solution to a symptom of a problem, it fails to address the supply and demand equation. And in the process, let’s be honest that rent controls will limit access to the sector and deprive the most vulnerable of a place to call home – the housing-have-nots.