Ignore the re-heated Thatcherism but listen to Truss: we need a growth plan

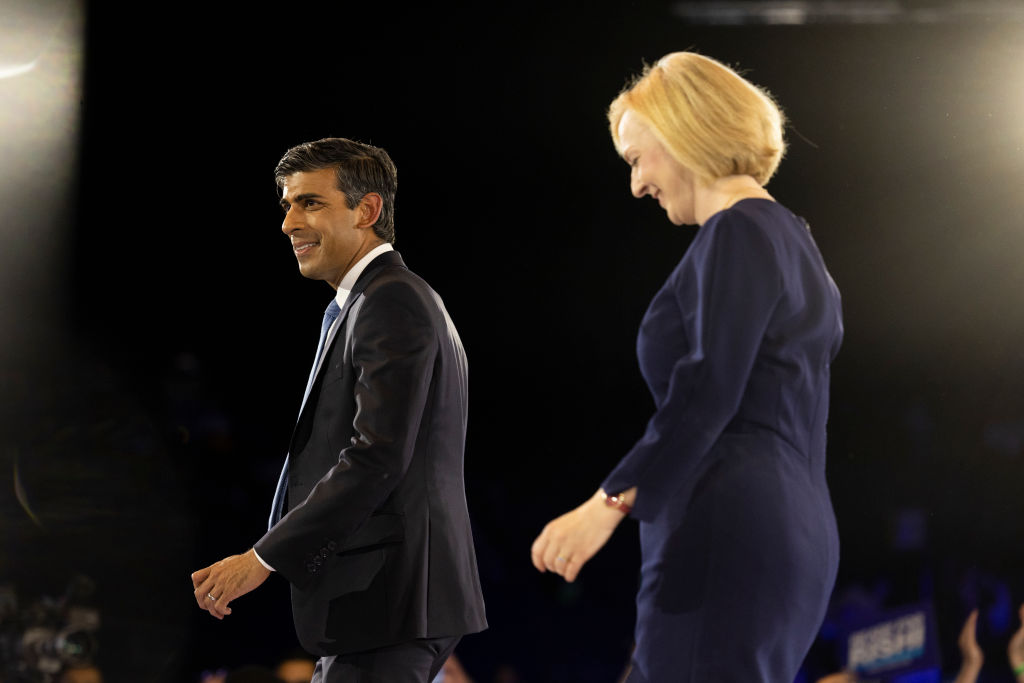

Liz Truss has played a blame-game for her failures. But her diagnosis was right – Britain is failing to touch the sides of America’s plan for growth. On this front, at least, Rishi Sunak needs to listen, writes Josh Williams.

Unrepentant, Liz Truss is on manoeuvres. Silent since her short premiership, this week she broke cover, speaking directly to the Conservative heartland, first writing in the Telegraph, then interviewed by Spectator editor, Fraser Nelson.

Her economic policies were, she still believes, the right ones. The fault for their abject failure rests not with her, but with the forces of economic orthodoxy – in places like the Office for Budget Responsibility, an institution that could have been named to spite her. The closest we got to mea culpa was her admission that “perhaps” the speed of her reforms was “a bridge too far”.

In truth, Truss’s re-heated Thatcherism was the wrong tonic for our times. Cutting taxes made sense in 1979, when the highest rate of income tax was 83 percent. Making a bonfire of red tape made sense when British business was in the doldrums, often stifled by poor management by the state.

Neither is a fair description of Britain today. The OECD describes market regulations in Britain as amongst the most competitive in the world. Britain’s top tax rate is lower than that of France and Germany, and on a par with Switzerland.

And yet Truss wasn’t entirely wrong. While her prescriptions were amiss, her diagnosis of what ails the British was right. Last week, the IMF predicted that only Britain’s economy, amongst all G7 countries, would shrink in 2023. Productivity has been persistently low since as early as 2007, long before the travails of Truss’s mini-budget and the Brexit vote. While Britain is home to one global economic titan – London – the rest of the country lags far behind on every measure.

Truss understood at least some of this. So did her predecessor, Boris Johnson. While “levelling up” never made it beyond an ill-defined mission and some pork-barrel politics, the underlying idea was that Britain needs growth, and that the need is particularly acute outside London.

Today, searching for what might one day be called Sunakism, it is impossible to divine a plan for growth. Admittedly, the first order of business for Sunak and his chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, was to fill the Liz Truss shaped hole in the nation’s finances. But when the Chancellor threatened to do more, presenting a growth plan at the end of last month, it was frustratingly broad and vague. His “four Es” – enterprise, education, employment and everywhere – weren’t just an offence to grammar. The Institute of Directors, whose support a Conservative Chancellor should covet, was withering on the substance, declaring that Hunt’s speech demanded a fifth E: “empty”.

In pursuit of growth, we would do well to lift our eyes to the United States, where the Biden administration is making a bold pitch for growth. While some here have long looked across the Atlantic for a model of free-market fundamentalism, America has in fact long been far more comfortable with industrial strategies that promote growth than we have been in Britain.

President Biden’s new Infrastructure Act is the most significant piece of industrial strategy the West has made in decades. The Infrastructure Act will invest $1.2tn in new, green infrastructure over the next ten years. The CHIPS Act will invest $280bn in building up America’s semi-conductor industry. The Inflation Reduction Act will subsidise green tech to the tune of at least $400bn.

Biden’s goals are threefold. First, to stimulate economic growth by rebuilding industrial might across the country. Second, to reduce America’s dependence on China, an international foe which has long distorted free trade with subsidies to gain a stranglehold over international supply chains. Third, to address the greatest long-term crisis the world faces – climate change – and become a green tech superpower in the process.

In Britain, investment like this is far beyond our means. However, we can begin to think like the American President. We too must look at the rise of green technology and ask where we can be a global leader. We too must reduce our reliance on adversaries, like Russian energy and Chinese manufacturing. And we too must spread growth across Britain. Today, there is little sign that our government is looking far beyond the immediate horizon. Ever since the financial crisis, Britain’s horizons have been limited to the considerable travails of today. Without a growth plan now, we will waste yet another tomorrow.