The power of our top football clubs is making the Premier League predictable

The Premier League kicks off again this weekend. And given the abysmal showing of our boys in the recent World Cup, a falling off of interest might be expected. But increasingly, our domestic football league attracts many of the best players from around the world.

A self-reinforcing process has been set up on a global scale: the more popular the Premier League and its clubs become worldwide, the more money is brought in through TV rights, merchandise sales and so forth. Even better players can then be employed, which increases the attractiveness of the league further.

Yet this very process makes the competition more boring, in the sense that the outcome of each Premier League season becomes more predictable. The places really worth playing for are the top five, which guarantee a club entry into the lucrative European competitions – the Champions League and Europa League.

If we step back in time to the days of the old Football League First Division (which became the Premier League in the 1990s), there was a far higher rate of turnover in these elite positions.

The names of the top five from 50 years ago, in the 1963-64 season, now look very familiar: Liverpool, Manchester United, Everton, Tottenham Hotspurs (Spurs) and Chelsea. But both three years before and after this season, just two of them finished in the top five.

Spurs was in fact the only one of the 1963-64 teams to claim a top five slot in each of these three seasons.

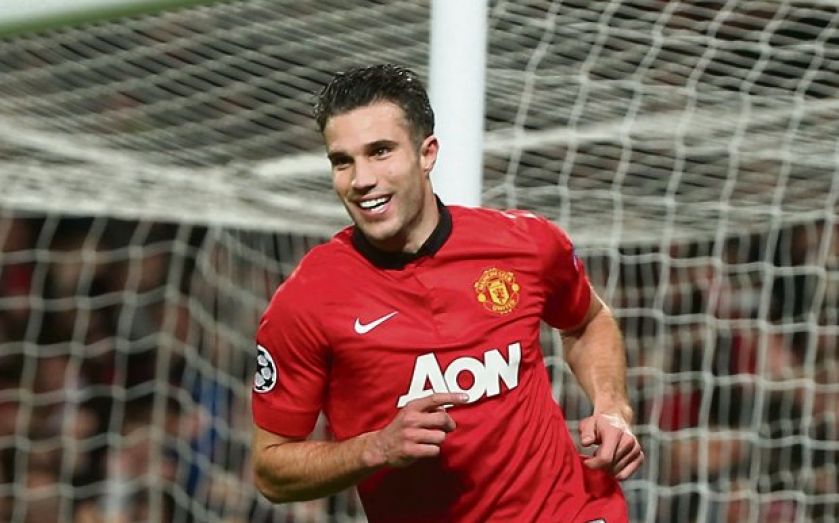

In recent years, turnover at the top has atrophied. Over the past ten seasons, Arsenal has been in the top five every time, and both Chelsea and Manchester United have appeared on nine occasions. Liverpool and Spurs both feature in six. Manchester City financially muscled its way to success in 2009-10, and has been in the top five ever since, winning last season’s league.

The only rank outsider to finish in the top five in the past decade was Newcastle, squeezing into fifth in 2011-12. The top half-dozen clubs now effectively form a league within a league.

The trend has accelerated during the Premier League’s lifetime. The winner in the opening season was, predictably, Manchester United. But, almost incredibly from the vantage point of 2014, the next four were Aston Villa, Norwich, Blackburn Rovers and QPR.

Even during the first decade, top five turnover fell. Manchester United filled one of the slots in each of the first 10 seasons, with Arsenal and Liverpool on eight and seven respectively. But Leeds, now long gone from the top flight, was in the top five on seven occasions. Back then, other clubs had a chance.

But the situation is not so dire as it has been since time immemorial in Scotland. No team apart from Celtic or Rangers has won Scotland’s top title since 1985.

And until Rangers went into liquidation in 2012, there was only a single season in which Celtic and Rangers did not fill the top two slots in the Scottish Premier League.