Port Talbot closure highlights uncomfortable truth about clinging onto the past

Port Talbot workers have been left in the lurch, but the steelworks’ closure is part and parcel of progress, writes Paul Ormerod

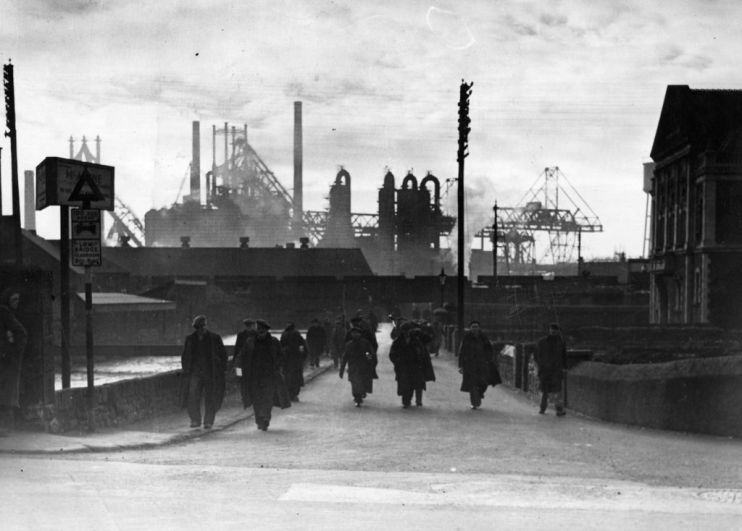

The decision by Tata Steel to shut the blast furnaces at the steelworks in Port Talbot, South Wales, has provoked outrage. Almost three quarters of the 4,000 workers at the plant will lose their jobs.

On the same day that the news broke, the government announced a £500m subsidy for Tata’s £1.25bn proposed investment on the same site. This is to build new electric arc furnaces, which produce steel in a much more eco-friendly way. But these will employ only a few hundred people.

Also on the same day, there was some very positive news. Google announced that construction had started on its £800m investment in a new datacentre in Waltham Cross, scheduled for completion next year. Data centres process, host and store the massive amounts of digital information that is critical for developing AI models.

The company said it was too early to say how many jobs would be created but it would need engineers, project managers, data centre technicians, electricians, catering and security personnel.

This follows on from Microsoft committing £2.5bn at the end of November to expand its AI datacentre infrastructure in the UK. Initial sites have been earmarked in London and Cardiff. A key aspect of the programme is to accelerate scientific discovery, with priority access being given to leading researchers at universities such as Cambridge, Oxford, Imperial and UCL.

The juxtaposition of the news on steel and AI does seem like a classic example of “out with the old, in with the new”. Indeed, the intention even at Port Talbot is to invest in a new and sustainable way of making steel, but with only a small fraction of the existing jobs.

Investment in new technology, in whatever guise, is obviously a good thing for the UK as a whole. But it also helps to spread prosperity.

A key aspect of the Google announcement is the range of jobs which will be generated. Scientists will be carrying out research at the frontiers of knowledge. Managerial posts will be needed. But, in addition, there will be a new demand for “electricians, catering and security” workers. Innovative firms create jobs at all levels of skills.

More generally, an important study by Phillip Aghion at the LSE and Richard Blundell at UCL shows that innovative firms offer a substantial pay premium for low and middle-skilled workers compared to less innovative ones. So innovative firms both create jobs and pay more.

All well and good for the towns where the likes of Google and Microsoft are investing. But the workers at Port Talbot are rather left in the lurch. Unfortunately for them, experience shows that It is almost always a mistake to subsidise and try and prop up industries which are in long-run decline. The coal mining industry is a classic example.

Seventy years ago, for example, there were 700,000 people in the UK employed in coal mining. Thirty years later, in the early 1980s just prior to the miners’ strike, this had fallen by almost half a million.

For many people, Lady Thatcher still bears the responsibility for defeating the miners and closing the pits. But the Labour Prime Ministers Harold Wilson and James Callaghan had already overseen the loss of considerably more mining jobs. The plain fact is that the mines would have closed anyway.

Areas can recover. On the site of the old Orgreave colliery in South Yorkshire, scene of a pitched battle between police and striking miners, is an Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre. Companies located there include Boeing, Rolls Royce and McLaren Automotive, creating jobs and good wages.

The industrial structure of a country constantly evolves. We need to embrace the future and not cling to the past.

Paul Ormerod is an economist at Volterra Partners LLP