The populist crusade against tax avoidance has turned into an assault on justice

If “tax avoidance” is the answer, what is the question? For many years it might have been: “what subject excites only a small number of tax lawyers and HMRC officials?” But in the age of attempted deficit reduction, “tax avoidance” – or rather “clamping down on tax avoidance” – is the answer you hear every time an “anti-austerity campaigner” is asked how they’d cut the deficit. Tax avoidance (legally arranging your affairs to lower your tax liability, as distinct from the illegal practice of tax evasion) has become a salient political issue. And as ever when governments respond to populist calls for something to be done, it’s leading to very bad law-making.

Some schemes seeking to reduce tax bills clearly go way beyond what the law intended. It is ultimately appropriate for tax to be paid. But there are a broad range of other government schemes where people are doing specifically what was intended, or taking advantage of terrible government drafting. It’s therefore important to get the process right to deal with difficult cases.

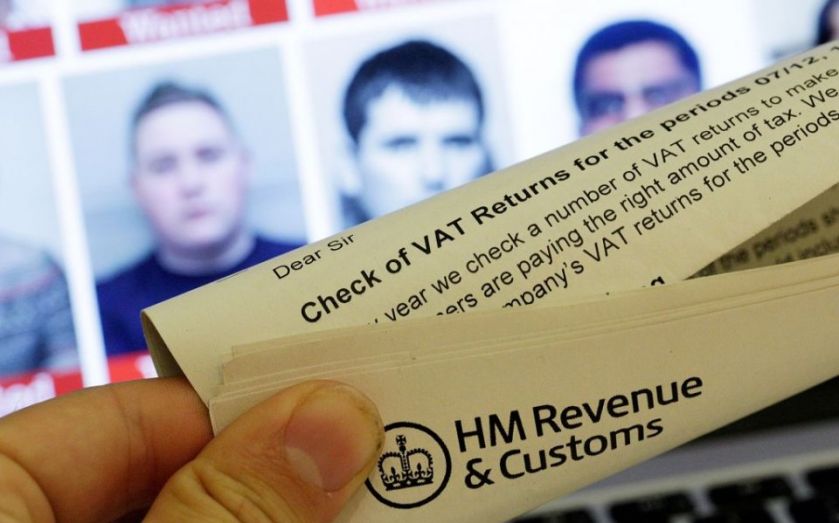

Rather than simplifying our tax law to avoid these ambiguities in the first place, the government’s reaction to the cacophony surrounding the supposed immorality of tax avoidance has been to hand a raft of new powers to HMRC. These will lead to a host of unfair and unjust outcomes – as flagged again last week when the National Insurance Contributions (NICs) Bill saw its third reading in the House of Lords. This will give HMRC the power to issue so-called “Accelerated Payment Notices” (APNs) in disputed tax cases for NICs – a power already granted last year for income tax.

The Orwellian name for this procedure suggests that it is merely a case of HMRC collecting money that is due to it more quickly. In reality it is an assault on the idea of “innocent until proven guilty”. Until last year, a disputed tax bill would not have to be paid until it was decided by a court of law. Yet these new notices in effect force taxpayers to pay upfront within 90 days – potentially requiring people to sell substantial assets, row back on business plans, or close businesses entirely in some cases – with taxpayers only then able to take potentially very costly legal action to find out that the tax was not due. This is not only unjust, but will also in effect be retrospectively applied on existing known tax avoidance schemes.

One would think that such a dramatic abandonment of our legal traditions would have to be well-justified. But the arguments put forward by the government are decidedly weak: first, that this will prevent tax avoiders from deliberately delaying the process of payment. And second, that HMRC wins 80 per cent of cases taken to court anyway.

Even on HMRC’s own numbers this means 20 per cent of cases will entail people having to make upfront payments for money that is not due – only getting it back if they take legal action. But in reality, HMRC currently only takes cases to court when it thinks it is more likely than not to win. It seems probable that these new powers will lead to a larger number of APNs being issued than currently observed court cases, potentially meaning many more people affected.

The government believes this action is worth it, whether due to its desire for more revenue (this is estimated to bring in an extra £4-7bn per year) or simply so that it is seen to be acting on an issue that many care about. But granting the power for HMRC to be judge, jury and executioner without legal process on disputed tax cases should be regarded as a very high cost indeed. With powers for HMRC to dip into our bank accounts also on the agenda, the current hysteria over tax avoidance is leading to some very dangerous precedents.