Political rivalry will keep Transport for London in eternal financial purgatory

People who live and work in London know the city would grind to a halt without an efficient public transport network. Almost half of the country’s 22 million public transport journeys undertaken every day are in London. Just a quarter of Londoners use a car to get to work – elsewhere it is 70 per cent.

I’m old enough to recall when London’s transport system was in a bad way. Back in 2000, when Transport for London (TfL) was created, tubes and buses were unreliable and an embarrassment to the city. Mayors and governments of varying political colours joined forces to revitalise the network. Both recognised the potential gains: for the Mayor, London got a better transport system and for the government, the whole country gained economically from a more successful capital. Upgraded infrastructure, new trains, modernised ticketing and extra capacity have been key to the city’s booming economy.

But this informal pact has collapsed, instead substituted by a fierce debate about who should fund the city’s public transport. Some believe London on its own should fund TfL. Others argue maintaining service levels and investment requires a public subsidy.

Before the pandemic, the loss of the operating subsidy from the Treasury meant TfL had to be self-sufficient. But this left it reliant on fare income. Around 70 per cent of TfL’s budget comes from paying passengers. A collapse in the number of people travelling during the pandemic decimated TfL’s finances, necessitating a series of short-term bailouts by government. Numbers using the network have still not recovered to 2019 levels, so financial support continues to be required.

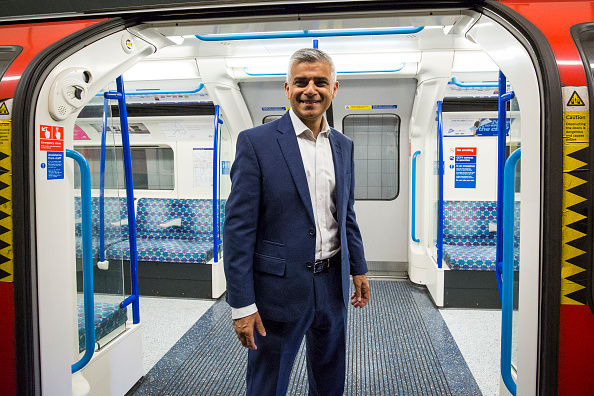

But with the government’s focus on battleground red wall seats beyond the M25, and with little to be gained politically from being kind to a Labour-dominated London, the capital’s chances look fairly slim. Ordinarily, a prime minister who is a former mayor should be an asset for London, but instead, the fighting of old battles has dominated the relationship with City Hall. The departure of the prime minister might lead to improved relations but there’s still time before September for the outgoing regime to give Sadiq Khan one final kicking. TfL funding is caught in the crossfire.

Hopefully a new prime minister could change the tone. Take the government’s line that it’s wrong for places like Barnsley to subsidise London’s transport network. With London contributing £30bn more a year to the Treasury than it receives, the opposite is true. What’s more, London can legitimately argue that the city retaining an extra billion towards funding TfL is cheap compared to the large returns generated for the nation’s coffers.

But fundamentally this is an asymmetric relationship – the Mayor might have the accountability for TfL, but the government is the one with deep pockets. With the government refusing to devolve power to levy and collect taxes, where else can the city turn but the Treasury? The problem is not one of too much devolution but rather too little.

If London had greater powers over taxes, city leaders might choose to raise more money to fund TfL. That being said, the Mayor’s powers permit the introduction of a pay-per-mile road user charging scheme which could generate considerable sums. But the Mayor will need to show strong leadership and political courage if he is to brave the inevitable partisan backlash against such a move.

Finally, a funding offer is on the table from the government, but City Hall have proposed a counteroffer. It’s unlikely the deal is without tough conditions attached, and the Mayor may find them politically unacceptable. Yesterday’s midday deadline came and went with statements from both sides suggesting there remains a considerable gap between their positions. There’s still time to put the partisan fighting to one side and recapture the spirit of TfL’s early years. It’s in everyone’s interests London’s public transport succeeds, and in no one’s for it to fail.