Oscar Wilde’s grandson Merlin Holland on Dorian Gray, censorship and posthumous pardons

After years in the back room, Oscar has finally found his way onto the Oxford English syllabus,” says Merlin Holland, with both pride and indignation.

Most of us in this noisy cafe off Carnaby Street wouldn’t be on first name terms with Oscar Wilde, but as his only living grandson and the sole executor of his estate, Holland has a greater claim than most.

“For the department to do that means he’s been accepted as rather more than a first-rate funny man for the very work that was once described as disgusting and immoral.”

The infamous work, of course, is The Picture of Dorian Gray, the only novel written by Wilde and the text that was used to convict him for gross indecency.

The fallout was devastating – not just for Wilde, who died alone and destitute in Paris three years after his release – but for his family, who had to deal with the shame rained down upon them by a Victorian society obsessed with moral posturing.

Hence Merlin’s surname is Holland rather than Wilde, an old family name chosen by Wilde’s wife Constance following his fall from grace.

“Some people ask me whether I’d ever change my name back and I thought about it at one stage,” he says. “Then I thought that I’m more my father’s son than I am my grandfather’s grandson and it’d be a posthumous slap in the face to my father.

"The second thing is that, if people have to ask and I explain why, it’s a permanent rebuke to Victorian morality.”

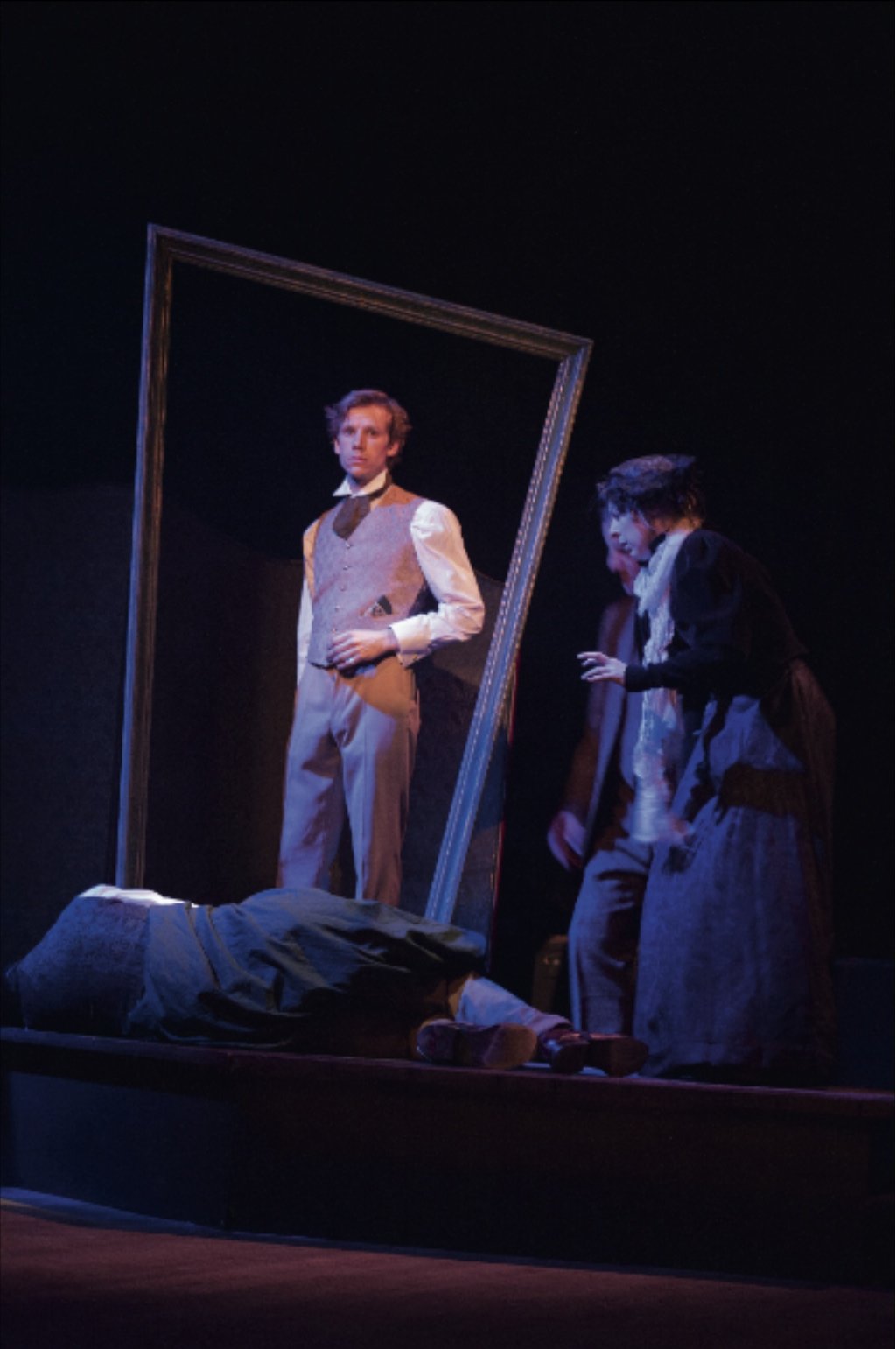

Guy Warren-Thomas in Trafalgar Studios' production of The Picture of Dorian Gray (Credit: Emily Hyland)

The Oxford English syllabus victory has been won exactly 125 years after the publication of Dorian Gray, and Holland feels the time is ripe to right another wrong.

He’s co-written a play of the novel – which has been done many times before – but in its original form.

The story of Gray’s hedonistic search for eternal youth was initially published in a magazine in 1880, but the editor censored it without Wilde’s knowledge, fearing the content would offend the delicate sensibilities of his readers.

A longer, revised version was published a year later, but Holland’s adaptation for Westminster-based theatre Trafalgar Studios restores many of the book’s nuances, whether it be a subtle hand on a shoulder or Basil’s bold declaration that “Somehow, I had never loved a woman”.

“When Wilde was in court accused of writing a sodomitical book,” he says, “they asked him whether Dorian’s sins were sodomy.

He replied, ‘What Dorian Gray’s sins are no one knows. He who finds them has brought them.’ And so, he wanted it to remain ambiguous and I think that’s what gives the work its complexity and sophistication.”

Like Shakespeare, many of Wilde’s phrases have fallen into common parlance without many people realising where they came from.

One in particular – “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about” – says more about the rise of Katie Hopkins than an entire year’s worth of media thinkpieces ever could.

In these personal-brand obsessed times, the novel’s depiction of dual lives – of the conflict between our public and private personas – is more apt than ever; don’t we all have a decaying portrait of ourselves just waiting to be dragged out into the harsh light of day.

“A German scientist has even pinpointed what he calls Dorian Gray Syndrome, which is a sort of pre-midlife crisis that happens in your 30s,” Holland notes, wryly.

Apart from this recent adaptation, he also co-adapted a touring production of The Trials of Oscar Wilde last year and published a book entitled Coffee with Oscar Wilde, an imagined conversation with his grandfather, along with collections of his letters and photographs.

Holland insists that his professional preoccupation with Wilde was “not conscious, it sort of took me over. But I’ve never, and I would never, claim that I inherited anything from him.”

That isn’t strictly true – for one thing he seems to have inherited a backlog of grief. He can’t go into it too much as he’s writing a book about it under the working title After Oscar, examining 100 years of shockwaves that emanated from his conviction.

“He’s caused more problems after his death and been involved, directly or indirectly, in more court cases than during his lifetime.

It’s all the squabbles between his friends and enemies, my father’s life before the First World War in the 20s and 30s, and it’s also a look globally at everything that happened as a result of the court case, which effectively destroyed my family.”

Ruper Mason playing Basil Hallward in the Trafalgar Studios production (Credit: Emily Hyland)

But what can be done about it now? At the end of last year’s Oscar-nominated film The Imitation Game, Alan Turing’s awful fate is flashed up onto the screen, followed by a rather meek posthumous pardon by the Queen. Since, its star Benedict Cumberbatch and self-confessed Wilde fanatic Stephen Fry have campaigned for all 49,000 men who were prosecuted for being gay to receive pardons.

While Holland thinks it was necessary in Turing’s case, he fails to see what such a pardon would achieve in his. “Is it going to make Oscar live longer than just over 46? Is it going to make my grandmother live longer than just over 40?

"The only thing one would get, I suppose, is recognition. But sadly, he was convicted under the law, he was tried and went to prison. There was no miscarriage of justice, it was a cruel law at the time.

“And if there is a posthumous pardon, it sort of says, ‘Oh well, the British Establishment is very sorry and all that, but we’ll just sweep it under the carpet, like it never happened.’ It’s just a sad and very unattractive fact in English history, and I think it should stay like that. You can’t change history.”

But to Holland – as to Wilde – fine words will always trump tragedy, so he ends our conversation with a worthy witticism. “I think one has to remember that wonderful quote by Sir Thomas Macauley, ‘There’s no sight more ridiculous than the British public in one of its periodic fits of morality.’”

The Picture of Dorian Gray is on at Trafalgar Studios until 16 February. Visit trafalgar-studios.co.uk for bookings.