Only liberal economic policies will allow us to adapt to disruptive technology

HOLLYWOOD producer Samuel Goldwyn once opined that “only a fool would make predictions – especially about the future.” It’s a wise view, but of little use to policymakers tackling big questions of the future.

With this in mind, one of the more interesting outlooks on the current state of western economies is the “structural” explanation. This says the pace of technological innovation and the rising importance of computers is accelerating, but our ability to adapt our skills and organisation to the trend isn’t keeping up. In Race Against The Machine, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee show how computer-based technology can render service jobs obsolete. Think supermarket staff replaced by the self-service check out; even the taxi driver, who may soon be put out of work by the driverless car.

These labour-saving technologies are the latest manifestation of progress – entrepreneurial harnessing of new technology, improving productivity. Mechanisation did it for agriculture, freeing up the labour which drove the industrial revolution. Mass production released labour into service industries. This new shifting of the technological frontier is merely the next stage in the process of making us richer.

Many worry that failure to adapt will lead to a structurally higher rate of unemployment, with lower-skilled people without capital permanently left behind. But this is unduly pessimistic. To work out what to do, policymakers must think what the labour market may look like in two or three decades. Here’s my forecast:

Simple service jobs will continue to be replaced by machines. There will be a rise in demand for skilled workers to maintain them, requiring skilled technicians, engineers and programmers. Internet-based sales will also accelerate, making attempts to “save the high street” futile.

The best chance of labour adjustment will come from providing a more highly skilled workforce, but – crucially – one that is even more independent, entrepreneurial and flexible. Thankfully, technology itself can help with skills and education. Online courses, video-based learning and better comparative testing can all help free resources for higher quality labour-intensive teaching elsewhere.

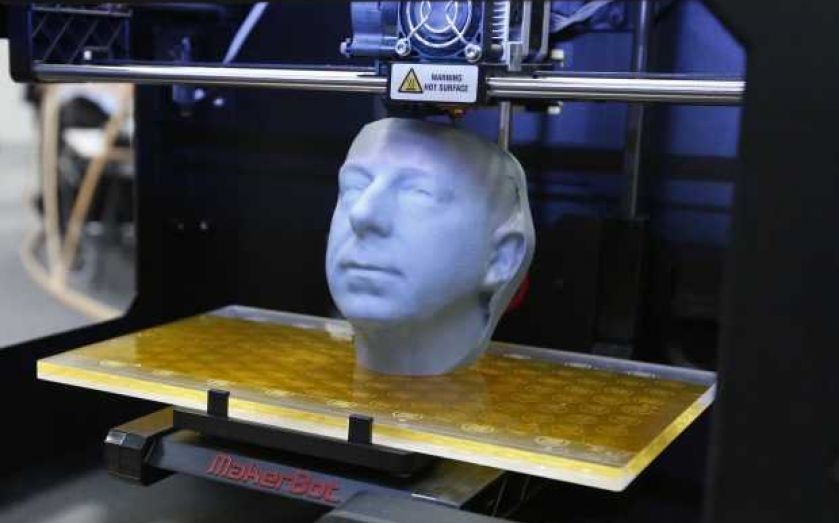

But it will be increasingly vital that policy enables people to set up their own businesses and agree flexible forms of employment. Cheaper technology for creating products at home – including 3D printers and other flexible production techniques – alongside more internet selling will mean many more people wishing to set up their own companies. This will likely be accentuated by the fact that, with more cheaply produced machine-products and services, there will be a premium for hand-made and crafted niche products and personalised services. The bottom line will be more enterprises, with many self-employed.

In fact, individuals are more likely to operate portfolio careers, less attached to any single firm, often learning across their working lives, and doing bits and pieces – flexibly and independently. The idea of the “job for life”, and employer-led benefits, already dwindling, will simply not exist.

These trends all lend themselves to liberal economic policies that allow for rigorous competition. But you can bet your life they’ll be met with fierce resistance from vested interests and advocates of government planning.

Ryan Bourne is head of economic research at the Centre for Policy Studies. @RyanCPS