Oliver Stone on Putin, nuclear power and feeling like an outsider

As we sit down to start our interview, Oliver Stone makes a point of putting his own dictaphone on the table to record our conversation. “To protect ourselves,” he says, before going on to speak non-stop for 45 minutes with absolutely no filter, on virtually any topic I raise, and quite a few I don’t.

He’s dressed in a smart blazer and shirt but he looks a little wild, his greying hair unruly and his brow wet from the baking sun that floods through the windows of the hotel suite. He clutches a yellow silk handkerchief, which he uses to alternately gesticulate and wipe his face.

Stone is here alongside his producing partner Fernando Sulichin to promote his new documentary, Nuclear Now, but he’s in no hurry to start talking about it.

To break the ice I mention that the boss of the toy company Mattel, who I had interviewed earlier that day, had jokingly asked if Stone would like to direct Barbie 2.

“Ridiculous,” Stone growls. “Ryan Gosling is wasting his time if he’s doing that shit for money. He should be doing more serious films. He shouldn’t be a part of this infantilization of Hollywood. Now it’s all fantasy, fantasy, fantasy, including all the war pictures: fantasy, fantasy. Even the Fast and Furious movies, which I used to enjoy, have become like Marvel movies. I mean, how many crashes can you see?”

Then, apropos of nothing, he changes the subject and suddenly we’re talking about how much he hates Virgin Airlines.

Richard Branson has a special place in hell reserved for him

“I went through a nightmare the other day. I was flying Virgin to London. [Richard] Branson has a special place in hell reserved for him. Dante couldn’t make this up. That plane he’s designed is a sardine can. The seats are like straitjackets. I haven’t slept a fucking inch.”

He sighs, putting his head in his hands. “It’s a depressing nightmare…”

He looks up, perhaps noticing the slightly baffled look on my face. “Oh yeah, so on the plane I watched John Wick, which is three hours and some. And I fell asleep about 778 times during it. I kept waking up and having to face him killing more people. It’s like the world has degenerated into non-logic.”

This is quite the introduction to the mind of Oliver Stone, the Oscar-winning director of stone-cold bangers including Platoon, Wall Street, Born on the Fourth of July and JFK, and writer of Midnight Express, Scarface and Natural Born Killers.

In his early nineties heyday his stories of troubled outsiders helped to define a generation of movies. Then his output began to slow, the number of duds eventually surpassing the number of hits, until he seemed to vacate the Hollywood mainstream altogether (his last big feature film was Snowden, starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt, in 2016).

Now aged 76, he is predominantly a documentary-maker, having worked alongside Sulichin on 16 films and counting. One of these – a turning point in his public image – was a series of sympathetic interviews conducted with Vladimir Putin, who he has more or less defended ever since.

“I was filming Snowden, who many people in the West still consider a traitor. Lunacy! He’s a real hero! He ended up in Moscow, so the last scenes of the film were shot there. The world is relatively small so [Putin] knew I was there. He agreed to meet me and talk about the Snowden affair, which I used as a basis to make the documentary.”

I wonder if he’s revised his opinion of the dictator since the invasion of Ukraine? “No,” he replies without missing a beat. Then he seems to catch himself: “I don’t want to get into that, because it’s not important and it would take over the other issues.”

But it is important, I suggest, because his views on Putin will affect the way people receive his work, including his new documentary.

“If it does, they’re missing the point. Because this is far bigger than this war. It’s bigger than Mr. Putin and Mr. Biden, it’s about the future.”

Stone is no stranger to controversy – ever since he wrote the screenplay for Midnight Express he has been accused of pushing a problematic vision of heroic machismo, and yet forty years later he’s still making movies. Is he impossible to cancel?

We’re cancelling too many talented people. The world has become more puritan and boring and narrow. We should entertain all kinds of thought. That’s how we get better.

“That’s a great expression. I like that. Because we’re cancelling too many talented people. The world has become more puritan and boring and narrow. We should entertain all kinds of thought. That’s how we get better.”

Given so many of his films seem to focus on outsiders, I wonder if he considers himself one? “I guess I do,” he replies wearily, touching his head with the handkerchief.

“I’m an only child. I never tried to fit the profile of a rebel but when you take in all my work, there is a lot of anger and rebellion.”

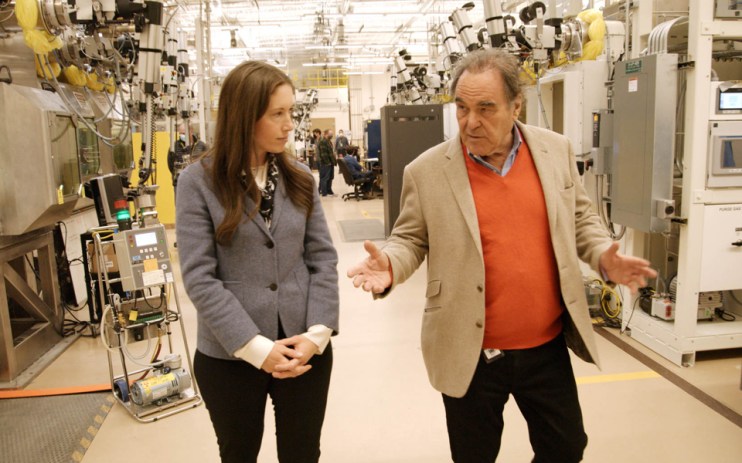

That anger is certainly evident in Nuclear Now. It’s a strange beast, made up of both archive footage and new material (mostly Stone interviewing nuclear scientists, often in Russia). Part infotainment, part pro-nuclear propaganda, it’s a kind of mash up of Adam Curtis and the sort of film a teacher might wheel into a classroom on a rainy day.

Clips from Godzilla and Dr. Strangelove sit beside endearingly low-fi scientific diagrams and computer generations of nuclear reactors.

“I wanted to explain nuclear energy,” he says. “What is it? What’s the origin? People all have an opinion but they just don’t know. I hate that.

“It’s like everyone has an opinion on Kennedy but they don’t do any research: ‘Oh yeah, he was killed from the front, blah, blah, blah. Oswald is guilty.’ It’s the same thing with nuclear, people are against it but their reasons are bogus. They haven’t even f***ing studied it. You have to start with knowledge.”

Stone acknowledges Al Gore’s seminal climate change documentary An Inconvenient Truth, which won him a Nobel Prize, was “important” but he thinks Gore missed the point; to paraphrase James Carville: it’s nuclear, stupid!

Nuclear energy is not the ugly sister that you hide in the back – it’s Cinderella. She’s not ugly, she’s beautiful

“People worry about nuclear waste and meanwhile the whole world is choking on fossil fuel waste. That’s silly. Trillions of dollars have been invested in solar and wind and hydropower. Everything possible is being discussed, except for nuclear. We had Davos last year and it’s not even on the agenda. It has to be on the agenda. It has to be talked about. It’s not the ugly sister that you hide in the back, you know, it’s Cinderella. She’s not ugly, she’s beautiful.”

Does he think Nuclear Now will have as big an impact as An Inconvenient Truth? “It should but it probably won’t, because we didn’t have Vice President Al Gore as our frontman. I wish we had an Einstein around, or an Oppenheimer, I could use him. But we don’t have that today. I guess we don’t cherish and value science the same way we used to.”

Studios only know how to push serial killers or the Tiger Dominator

Perhaps that contributed to how difficult it was to get Nuclear Now made in the first place. “Studios know how to push serial killers or the Tiger Dominator,” says Sulichin, “But not things that will educate or enlighten. There are two documentary markets, the market for films with a murderer or a serial killer, which will get a good deal. Then you have other films, which are tough.

“It was hard to raise the money for Nuclear Now and it was hard to distribute. But it’s a good film, and when the film is good, people will watch it. The word is spreading. The film has had great success in the United States and we are slowly, with a level of effort, achieving beyond our goals. Last week, this movie was number one on iTunes, which was a pleasant surprise.”

So how did they get it funded?

“Through myself and other people I know who are philanthropists,” says Sulichin. “A Polish woman who makes uniforms for nurses, entrepreneurs from Silicon Valley, a lot of interesting people who believe in nuclear. We accepted credit cards, bitcoins.”

This is a narrative I feel Stone can get behind, pushing his righteous agenda in the face of overwhelming odds.

Nuclear Now ends not with an apocalypse but a vision for a slightly cheesy possible future: crystal-clear water and verdant forests, an antediluvian paradise, brought to you by nuclear fission.

“I wanted the Barbie doll ending! The film is depressing in the beginning. We throw all the shit in your face and say, ‘Look, this is the worst it can be’. And then we end with positive notions of the future, how nuclear can make… more of a Barbie world.”

- Nuclear Now is out now. For information on how to watch go to nuclearnowfilm.com