The best of travel: Why Okinawa is Japan’s Alex Garland destination

Throughout January we’re remembering better times and sunnier climes by reposting some of our favourite travel stories from the last decade. In this instalment, our Life&Style editor Steve Dinneen ventures to the remote Japanese archipelago of Okinawa.

•••

Everyone who is serious about travel should have their Alex Garland destination, somewhere you can casually name-drop at dinner parties, safe in the knowledge that nobody else will have been.

Garland immortalised – and perhaps doomed – Thailand’s then-pristine Koh Phangan when he wrote about it in his novel The Beach. That was in 1996, just before the rise to ubiquity of the “gap yah”, that middle-class rite of passage that ensured those islands are now as famous for amphetamine-laced Red Bull and genital ping pong as they are hidden waterfalls and coral sands.

The world is a lot smaller now, its remaining Koh Phangans fewer and farther between. The internet and cheap international travel mean a destination needs to be seriously out of the way for it to hold any currency among people who are impressed by that kind of thing. Mine is a place called Iriomote-jima, a subtropical island in the East China Sea, population: 2,000.

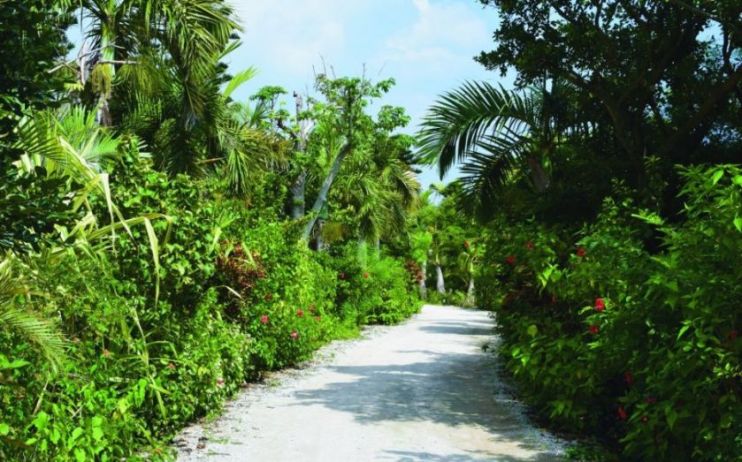

One of the southernmost of Japan’s Okinawa islands (it’s 300km from Taiwan and 1,000km from the Japanese mainland), it’s 90 per cent covered by rainforest and mangroves. The majority of it has never so much as heard a human footstep.

During my stay I saw – and this is no exaggeration – roughly a dozen other tourists. This is partly because Iriomote is a real pain to get to. From the UK it’s an 11-hour flight to Hong Kong, followed by a three-hour flight to Naha, the Okinawan capital, followed by an hour flight to Ishigaki, the closest island airport, after which you’ll have to hop on a ferry for another 45 minutes. More than enough to put off most Western tourists.

The Okinawan islands, though – even the ones this far from the mainland – are popular with the Japanese, and fill up quickly during the summer. Thankfully, as with many aspects of Japanese culture, there are rigid conventions concerning annual leave: come 1 September, it’s time to don your shirt and tie, squeeze onto the Shinkansen and get back to work, leaving this island blissfully unpeopled.

There’s a small catch – September is the rainy season. There’s twice as much precipitation as in July, for example (the optimal time of year from a weather point of view). In the two days I stopped over in Naha (at the north of the archipelago, nearest the mainland) it poured relentlessly; grey, sullen skies emptying until every street became a brook.

The southern islands have their own micro-climates and you take your chances with the weather gods. They happened to smile on me. The mercury rarely dropped below 30, and only occasional showers cut through the scorching sun and suffocating humidity.

Iriomote is how I imagine Koh Phangan 30 years ago: dense forest and undisturbed beaches, the soundscape made up of nothing but crickets and tropical birds. I hired a local guide for £40 a day, who took me out in a kayak – the only way to traverse the mangroves and waterways that make up Iriomote. The scenery is spectacular – ancient green hills rising from the sea, Dali-esque shapes carved into the limestone rocks. Making your way to the best beaches, tucked away in remote coves, takes time; I kayaked for two and a half hours in the mid-day heat, and each time the oar dug into my blistered hands I was reminded I’d have to make the same journey back.

Eventually I cut into a long, curved inlet and disembarked at a stretch of beach where caves filled with shrimp-like crustaceans jutted out into the jungle. Wading into the sea was like standing in a bath – the coral reefs trap water, which heats up all summer, reaching more than 30 degrees by this time of year. Snorkelling out a few metres opened up an underwater vista to rival any in the world; vast tendril-like coral outcrops were home to countless parrot fish, clown fish, angel fish and writhing purple and pink anemone. Visibility was 30 metres or more – there’s a reason most people who venture this far come for the scuba-diving (famous sunken vessels and underwater monuments also lurk nearby).

I stayed in Iriomote Eco Village, one of the few accommodation options on the island and by far the most luxurious, consisting of a handful of villas clustered around an outdoor pool, all with views out to sea. The pool is out of bounds after dark, the lights attracting thousands of moths and beetles the size of your fist.

The food here is traditional, with lots of variations of tofu and seaweed broth, and one rather difficult to swallow delicacy involving fish guts. A short drive away is a causeway serviced by water buffalo, the lumbering creatures taking you to a landscaped island filled with vivid flowers and gigantic orb-web spiders.

This island paradise had seemed a long way off when I landed in Naha, the low-rise concrete sprawl and population centre of the archipelago, which was made gloomier still by the seemingly endless monsoon.

As an important naval location, the Americans carved their way through Okinawa during the Second World War, establishing bases that still exist today, and you can see plenty of military-types watching baseball in the local bars. Out of the low-rent bustle of the town, Naha takes on a sullen kind of beauty, with shrines and burial complexes dotted down alleys behind houses (ancestor worship is big here, and it might be paying off; Okinawan women have the longest life expectancy in the world).

Away from the main town and the handful of tourist spots, westerners are few and far between and you’re unlikely to find many English speakers. I whiled away my evenings drinking Kirin in a tiny karaoke bar, which became progressively fuller as the owner called her friends to show off her newly acquired gaijin (“foreigners”). She introduced me to fried goya – a bitter vegetable a bit like courgette – and Habushu, an Okinawan spirit with a dead pit viper curled in the bottle (peppery, not unpleasant).

Some 400km south west lay Ishigaki, my next stop. If you rent a car, this fairly large island has some great beaches, although it’s also the most touristy of the Yaeyama archipelago (consisting of the southern Okinawan islands), full of shops selling flip-flops and tourist tat – I found one baseball cap emblazoned with the words “More Womanizer”. Keep a look-out for the twin ceramic lion-dog creatures guarding the houses here, one with its mouth open to catch good luck, the other with its jaws clamped shut to keep hold of it.

Rather implausibly this tiny, remote island is renowned for the quality of its beef, which is served Korean barbecue-style; very good indeed. Ishigaki, though, is best used as a jumping board to its more salubrious neighbours – the aforementioned Iriomote and the more accessible Taketomi, which is a 15-minute ferry ride away.

Best explored by bicycle, Taketomi is another Garland destination – tranquil beaches, warm seas, deserted local bars serving ramen and katsu curry. It’s as far from the lights and noise of Tokyo as you could get, but still carries with it the unmistakeable air of Japan. I left my camera and clothes lying on the beach for hours while I swam, confident they would still be there when I returned. You don’t get that in Thailand.