Ofgem cannot fix the energy market unless ministers scrap the price cap

Even among regulators, the energy watchdog Ofgem has had a rough time of it.

Over the past couple of years, it has seen 30 suppliers go bust on its watch, all the while seeing household bills spiral to record highs.

There is precious little sign of the latter being resolved anytime soon.

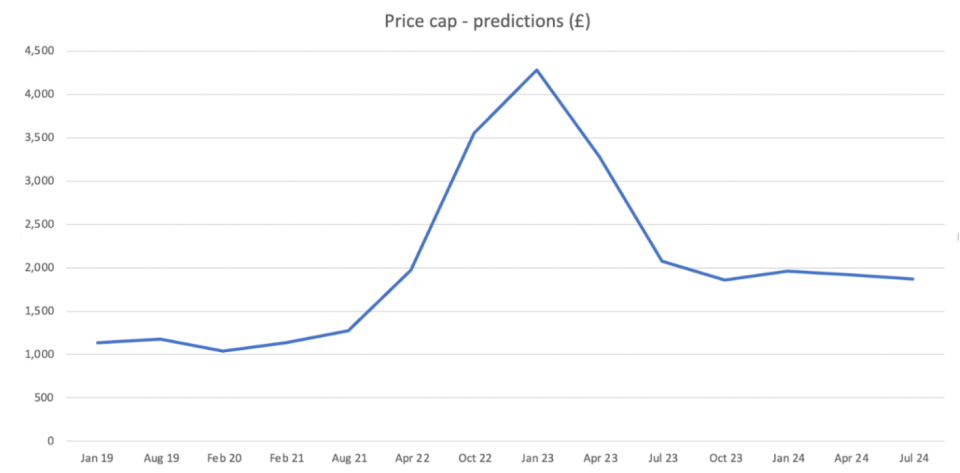

While the initial spike seen in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may have dissipated, analysts expect higher bills to stick around until the country is running on cheap renewables – a worthwhile goal, but one that will be frightfully expensive to achieve in the meantime.

In a normal market, high prices would be passed on to customers.

But the energy price cap forbids suppliers from doing that, so Ofgem has been forced to move in a different direction – one that will give them greater confidence suppliers will keep their heads above water, but will do little for competition in the energy sector.

Price cap pain

Stung by criticism after the costly collapse of a host of suppliers, Ofgem has pushed forward with capital adequacy requirements, financial resilience tests, net asset value rules, and partial ringfencing across the industry.

This marks a shift from a pre-2020 world when policy dictated that the market became less regulated, and more competitive.

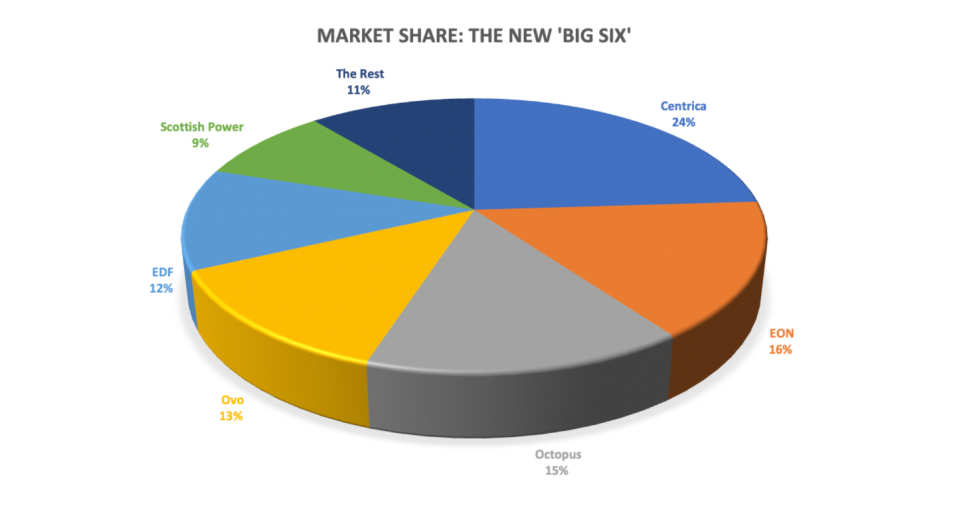

Indeed after a public panic about the power of the Big Six, the market exploded to a high of 70 suppliers in 2018.

That wasn’t entirely a bad thing – for all the weaker players, it was also the climate that allowed new entrants such as Octopus Energy and Ovo Energy to take on bloated incumbents and provide much-needed competition.

But when prices roses, the price cap hit those smaller, challenger players harder.

Energy firms may have poorly organised their financial affairs, yet the reality remains that it was near impossible for most of the fallen suppliers to survive a situation where they were unable to pass on a sustained hike in wholesale costs to customers.

For instance, Bulb may have pursued an unsustainable growth model to become the seventh largest supplier with 1.5m customers – yet, the final blow was the rate of the price cap, which meant it could only charge customers 70p per therm despite wholesale prices rising to £4 per therm for supply.

The risk is that unless the price cap is removed, further collapses could happen again – irrespective of how robust Ofgem seeks to make the suppliers it regulates.

Big Six benefit from Ofgem’s clean-up

What is also noteworthy is the crisis favoured the biggest suppliers with the deepest pockets, which were able to manage a sustained period of loss making.

Centrica, owner of British Gas, snapped up multiple fallen entrants, with the Big Six’s market share rising to over 90 per cent following Octopus’ takeover of Bulb late last year.

This was the very situation the government desperately sought to avoid when it first made reforms to the domestic supplier market a decade ago.

Ofgem’s tightening financial reforms are laudable but could risk stifling innovation and new entrants to the market, and combined with the continued existence of the price cap – it is challenging to see how any new supplier could thrive and present a new proposition to customers.

Last week, Brearley called for the price cap to be reconsidered, questioning whether the “very broad and crude” mechanism is still fit for purpose.

He is not alone, with Ovo chief executive Raman Bhatia and Good Energy boss Nigel Pocklington also confirming to City A.M. that the cap needs to be either redesigned or abolished.

However, such a decision is not in Ofgem’s gift – with the price cap pushed through Parliament in 2018 before being enacted across the industry the following year.

This means, irrespective of Ofgem’s handling of the crisis and clean-up operation, one of the chief inhibitors to fixing the market has to be dealt with by ministers.

With an election coming up next winter, the government is running out of time to address challenges in the energy market.

The industry must put more pressure on Whitehall to scrap the broken price cap – or risk more suppliers collapsing in the face of future market instability and less competition and innovation for customers.