No showing off: The paradox at the heart of British men’s style

The English have a strange relationship to men’s style. Every gentleman has conflicting voices, a Jeeves and a Wooster on either shoulder: Bertie with his brass-buttoned mess jacket and Old Etonian spats, his valet with an eyebrow raised in polite disapproval. Nowhere better is this duality exemplified than in the British Army. Regiments do everything they can to distinguish their uniforms, with piping and braid, buttons and badges, but once you get a group of officers together in civvies, they will dress almost completely alike: navy blazers, checked shirts, brightly coloured chinos or cords.

Undoubtedly this stems from the great British reluctance to show off. To stand out is, for polite society, rather vulgar and unbecoming. Tall poppy syndrome, know-it-all, too big for your boots, fashion victim: it runs through our language. But even the British are human, and there is a desire in most of us to unleash our inner peacock from time to time, to show a bit of ankle.

How can a gentleman square this circle, reconcile these two deep-seated urges? It requires balance, judgement and a dash of bravery. Sometimes you will get it wrong, but mistakes are there to be learned from, and broken bones heal all the stronger.

Watches are the subject of intense interest to a certain subsection of horological geeks. It is generally held by the expert community than a man needs a minimum of three watches: a dress timepiece which is a study in simplicity, a rugged sports watch for the extreme activities we all pretend to pursue, and an ‘intermediate’ device which can take its wearer from a casual supper to an impromptu tennis game (choose your own polarities as appropriate).

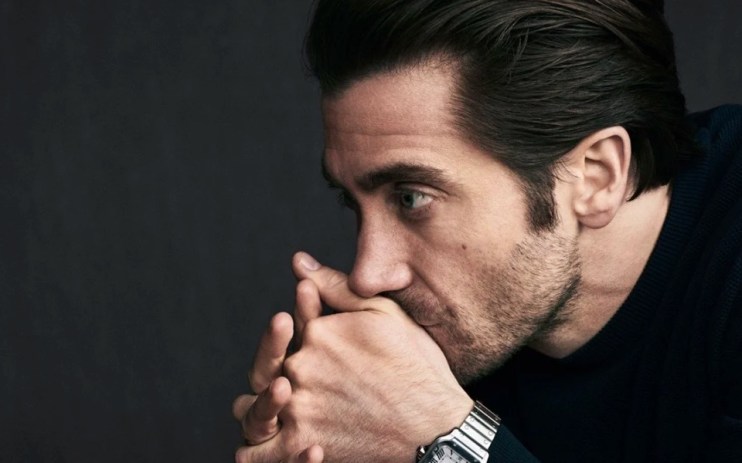

So a timepiece is a good opportunity to be creative and distinctive without shouting too loudly. A go-anywhere, bulletproof watch like the Breitling Endurance is best left for outdoor pursuits; and if you want to cachet of a major brand like Rolex, Cartier or Patek Philippe, think about something slightly out of the ordinary, or which says something about you beyond your spending power. I wear a TAG Heuer Monaco, partly because it still has a quirky, avant garde appearance, partly because it carries echoes of the glamour of motor racing, Monaco, Steve McQueen, which I adore, and partly because it was my father’s. Browse the catalogues, size up different makes and models, see what feels comfortable. It will show.

Men should approach other jewellery with extreme caution. A wedding band is exempt, of course, as is the counterpart on the right hand for same-sex couples. Beyond that, the neck chain had a great revival last year after its modelling by Paul Mescal as Connell in BBC3’s Normal People; but anything more than a thin item worn underneath clothes is pulling you towards the world of the eager-to-impress market trader.

Signet rings are, in all truth, the alpha and omega of men’s jewellery. They are discreet but laden with meaning, assuming they carry some kind of crest. This might be the family arms, the wearer’s initials or a symbol significant to them in some other way. If you worry about the message it will send, imagine describing it to someone else as if worn by a third person: “His signet ring had x engraved on it…” Do you nod or screw up your face? That’s your answer.

As we move towards a truly paperless society, fewer people carry pens (I always do, but I was a clerk for more than a decade: it’s ingrained). But they are a good way of showing a little style and flair on occasion. Unless you are richer than Croesus and can make it into a reverse snobbery, no-one will be impressed if you produced a chewed, capless Bic biro from your pocket; but people will notice if you smoothly and casually pull out a well-engineered, good-looking ballpoint or fountain pen.

Mont Blanc, of course, is the epitome of expensive writing products, and their pens are both reliable and elegant. Pelikan, a German brand based in Hanover, produce some beautiful hand-lacquered fountain pens which will catch the eye, while Diplomat Pens, founded in 1922, have a pleasingly Teutonic Art Deco air about them without breaking the bank. Visconti are relative newcomers (1988) but use innovative materials like reformed lava from Mount Etna to produce striking and distinctive writing tools.

In the end, it is all about attitude. You must be brave—standing out from the crowd is never for cowards—but you must also know when you have gone too far. To be discreetly distinctive, to offer a flash of dandyism without shouting from the rooftops, pick your battles, whether it be watches, rings or pens; go to the extreme of where you feel comfortable; then push 10 per cent further. You’ll know very quickly whether you’ve got it right. And when you have, hold on to the bravery that got you there. Don’t disappear into the background, but cut a dash of your own. After all, as the young people say, you only live once.