Myth-Busting: Money printing must create inflation

London ranks ninth on the UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index for residential properties. Like in many other countries, property prices in the United Kingdom reached an all-time high in 2020. A global pandemic with sudden mass unemployment should have forced UK citizens to sell their homes, but the furlough policies, stamp duty holidays, and record-low interest rates more than counterbalanced that.

A two-bedroom apartment with 1,000 square feet of living space in a posh neighbourhood like Hampstead in North West London costs about £1.5 million. The rent is approximately £3,000 per month, which equates to a measly gross rental yield of 2.4%. After accounting for maintenance and taxes, it’s more like 1.7%. Many of the houses in that area are more than a century old and need lots of love.

Although such a low yield may seem unattractive to buy-to-let owners, it was considerably worse throughout most of the last decade when the cost of financing was above the rental yield. Buyers were purely betting on price appreciation and willing to accept negative cash flow during their investment period.

Join this free event hosted by CFA Institute to hear from global regulators and policymakers on the most urgent questions faced by financial markets and investors today, such as ESG investing and the shape of the economic recovery post Covid19.

Now, thanks to COVID-19 and the Bank of England (BOE), financing costs are less than the rental income, and the cash flow of property investors has turned positive. For those considering buying a property for their own use, paying interest and amortization is now often cheaper than renting. What an odd world.

But buying an apartment in neighbourhoods like Hampstead tends to require at least 25% of equity as banks have become more conservative since the global financial crisis (GFC). If a potential buyer was successful enough to save about several hundred thousand pounds for a down payment, they’ll still need to eventually repay the £1.1-million loan. From a pre-tax perspective, this implies almost twice the amount of money that needs to be earned.

Some potential buyers are actively betting on inflation to help reduce the debt load over time. The theory is that all the monetary and fiscal policies of the last decade will lead to higher inflation. Income and real asset valuations should increase along with inflation, but the loan amount stays the same and erodes in real terms.

Is this the wishful thinking of property speculators or does the data support the theory?

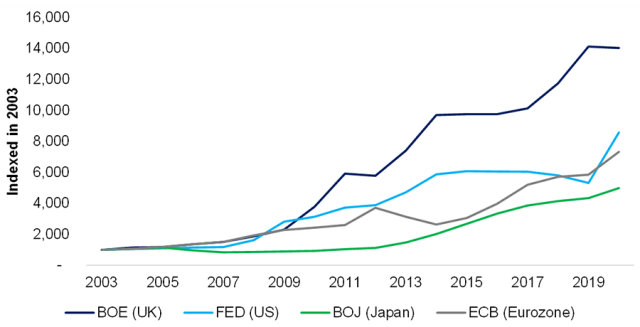

Central bank balance sheet expansion

Central banks are often credited with saving the world with their aggressive monetary stimulus during the GFC in 2008. But the crisis is more than a decade behind us and the same basic policies are still in place. Central bank balance sheets keep on expanding. In countries like Germany, this continuous money printing is viewed with pure horror given its association with the hyperinflation of the Weimar Republic in the 1920s.

With the COVID-19 crisis, the central banks have kicked their money printing into an even higher gear. The US Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has breached $7 trillion, which is comparable to the European Central Bank (ECB)’s €7 trillion. The central banks seem to have chained themselves to the public markets and feel forced to step in each time stocks drop meaningfully.

The unnatural consequences of this behaviour are becoming more and more obvious. For example, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) owns more than 75% of the exchange-traded funds (ETFs) domiciled there.

Central Bank Balance Sheet Expansion

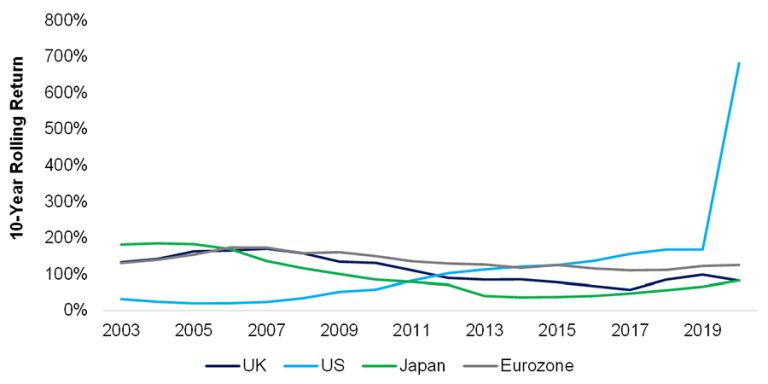

Money supply

There are various metrics to measure the money supply. M1 represents all the physical money in circulation, both in cash and in checking accounts, and has been trending lower in the United States, Europe, United Kingdom, and Japan since the 1980s.

None of the monetary stimulus conducted since 2009 has influenced money circulation. That holds true even with broader money supply measures like M2 or M3 that include savings deposits and money market mutual funds.

In 2020, the US government issued COVID-19 stimulus checks which significantly affected M1 by vastly increasing the cash in circulation. The UK and EU governments responded differently and did not issue direct cash payments to their citizens, so M1 in these countries remained the same.

Increase in M1 Money Supply

The change represents 10-year rolling returns.

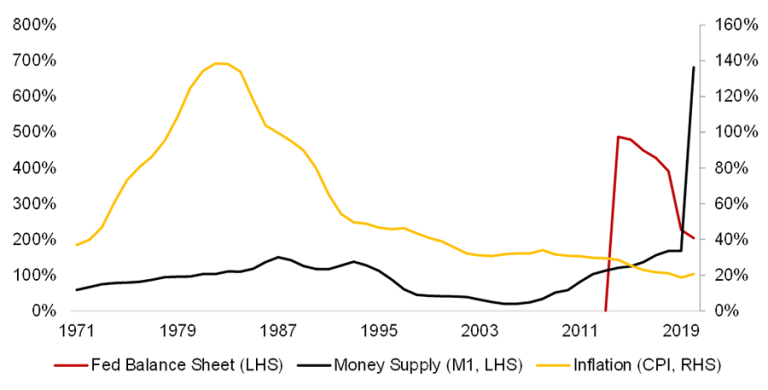

Central bank expansion, money supply and inflation in the United States

The same three economic variables in the United States, show the same increase in the central bank balance sheet as in other markets and only muted effects on money supply and inflation. Furthermore, inflation can occur without meaningful changes in the money supply, for example, during the oil crisis in the 1970s.

Some investors are betting on inflation to follow the spike in the money supply in 2020. While this is possible, the money supply has been increasing for more than a decade but inflation has fallen consistently over the same time period.

Central Bank Expansion, Money Supply and Inflation: United States

Axes show 10-year rolling returns.

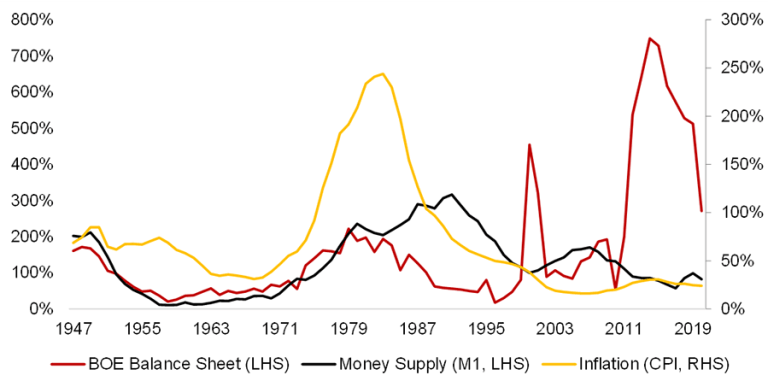

Central bank expansion, money supply and inflation in the United Kingdom

The BOE has time series that goes back to way before the Middle Ages. It is an El Dorado for economists and financial data aficionados.

The UK data highlights a strong positive correlation between the BOE’s balance sheet, money supply, and inflation between 1947 and 1995. But thereafter, the relationships broke down. Money supply and inflation still moved in tandem, but the central bank activity seemed largely irrelevant.

We are not economists and do not know why these relationships changed. It could be due to the type of central bank activity. Maybe central bank activities used to be directly linked to the money supply while modern policies are more focused on influencing financial markets.

Central Bank Expansion, Money Supply and Inflation: United Kingdom

Axes show 10-year rolling returns

Further thoughts

Similar analysis on the eurozone reflects the same trend: Central bank money printing is largely irrelevant to money supply and inflation.

Given their typical mandate to create moderate inflation, the all-powerful central banks seem quite powerless. Or they are simply fighting forces they cannot overcome: namely, the negative demographics and negative productivity growth that contribute to low economic growth.

Should investors worry about the mass money printing by central banks? Certainly. It has distorted financial markets and inflated prices across asset classes. But perhaps this simply leads to lower future returns rather than higher inflation.

Still, if more direct fiscal or monetary stimulus is delivered on an ongoing basis, investors may have greater cause for concern. History shows that this is a recipe for disaster for renters and owners alike.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

By Nicolas Rabener, managing director of FactorResearch, which provides quantitative solutions for factor investing.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / megaflopp