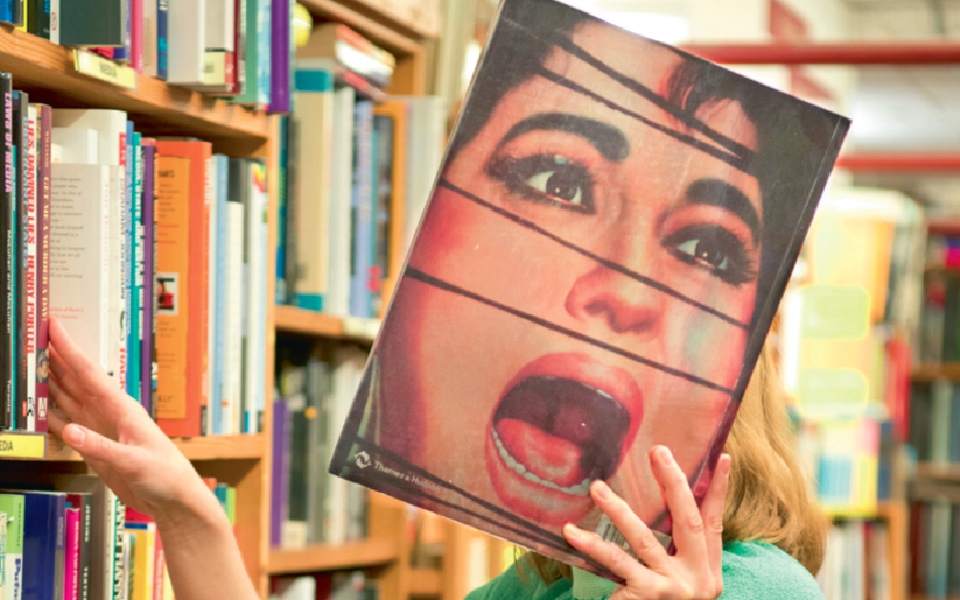

Lost for words: The indie bookshop has weathered many storms, from the rise of Amazon to rising rents. But its future has never looked so perilous

Prospero’s Books stood on Crouch End Broadway for 10 years. I remember it, though not well. The bookshops of my childhood memories are all vaguely similar – they were places where I’d be both happy and bored.

To hear locals tell it, there wasn’t any sign that Prospero’s was in trouble. It seemed to plod along as it always had, never doing much business, but then that’s just bookselling, isn’t it? It’s a precarious industry at the best of times: too precarious, as it turned out, for Prospero’s went bust in 2011 and was replaced on the Broadway by an ice cream parlour.

Over 600 independent bookshops closed down between 2005 and 2015. This represents almost half of the indies in the UK, and though the rate of closure has slowed, 2016 saw a contraction in their numbers for the 11th year in a row. It’s a problem of such magnitude that thinking about long-term solutions, rather than mere survival, seems quixotic.

They face an assortment of deadly threats: the most immediate is rising rents and business rates, and the accompanying problem of security of tenure; and the prospect of a chain opening a branch nearby and, if they do, whether to sell up immediately or compensate by serving coffee and selling board games.

Then there is the now-receding threat of an ebook revolution, which is enmeshed with the much larger and more frightening problem posed by the internet; the existential crisis of disinterest and drift – the sense, conveyed by many booksellers I spoke to, that people simply don’t read as much as they used to, that Netflix and gaming have indelibly marked the world of literature, which now resides upstream from our attention spans.

“Very poor,” is Chris Edwards’ clipped response when I ask him about the future prospects of his industry. Edwards is the manager of Skoob, an independent close to Russell Square. “Since we reopened in 2007, 14 bookshops have closed within 1,500 metres of us.” He emits an almighty sigh. “But we get new coffee shops and new hairdressers everywhere.”

He’s right; despite fretting about chains, the number of independent shops on the British high street has in fact risen every year since 2010. The main beneficiaries of this new economy, however, are industries that are impervious to the locust-like tendencies of the internet. Restaurants, bars, tanning shops and tattoo parlours are all good business. Prospero’s Books becomes Riley Ice Cream Café, because you can’t eat ice cream online.

The profile of Amazon looms large amidst this rapid change. “Amazon is killing the book business,” reads one headline; “Amazon killed the bookstore. So it’s opening a bookstore,” deadpans another. And if you mention its name around any bookseller, their faces will darken and their mouths will form a scowl. Even Mairi Oliver, who runs the radical, Edinburgh-based Lighthouse Books, and speaks with the energy of the naturally optimistic, becomes exasperated. “We get people who barcode scan our books into an Amazon basket. I have to tell them we’re not a shop window for the world wide web.”

Another bookseller, who didn’t want to be named, told me that when customers come in and ask for a book they don’t have, he’ll simply hide the computer screen and purchase it online, buying it for, say, £12, and charging £15 for collection the following day. Extrapolate that to a loyal customer base of ageing locals who perhaps haven’t entirely gotten to grips with the internet, and it’s a business model.

If this suggests that independent bookselling is locked into some absurd and inexorable death spiral, talking to booksellers should disabuse you of such apocalypticism. They tend to be phlegmatic about such things; they know their industry is in a perilous state, but that’s just part of the deal. They do it, for want of a better phrase, out of love. “We are not getting rich from this,” laughs Bruno Sancho, who works at the second-hand Black Gull Books in East Finchley.

Bruno is the archetypal bookshop-romantic. “I like books. I like to read,” he tells me. “I was probably the worst student there’s ever been in high school. I didn’t finish school or anything because they’d tell me to read one book and I’d want to read another. But I always liked reading, so I started working in bookshops. Books Etc [a subsidiary of Borders that shut in 2009, hemorrhaging money] was first, then I moved to Spain and worked in publishing. So I’ve always worked in the same trade.”

I visited Black Gull in the heaving rain, and there was something incredibly comforting about it; it’s quite dark in there, and there’s little space between the bookshelves, so you get the sense that it might all collapse around you. The books themselves are eccentrically chosen, and individually priced in pencil. It’s the kind of place I can vividly imagine racking up bills of many thousands of pounds, but of course I don’t.

And therein lies the rub: it must be infuriating to work somewhere that receives so much more affection than commerce, somewhere people will sit and consume your produce, only to leave without buying anything. But it’s also perhaps true that such places are the fruit of a healthy society, one that knows, at least a little, of value as well as price.

Second-hand bookshops are, by nature, somewhat protected from the threats that ordinary independents face. Because their books come from personal collections and book fairs, rather than distributors, they can charge what they like – but even so, they aren’t exactly rolling in it.

“It’s profitable in that we still sell some books,” Bruno says. “We are selling the same amount of books but now we have to pay more bills, we’re paying higher business rates, we’re paying higher rent, higher wages as well, and we are just selling the same books. So the profit margin is smaller and it’s shrinking by the day.”

Edwards gives a similar diagnosis. For him, the problem is older and more prosaic than automation. “Amazon is a positive thing,” he says, to my surprise. “They’ve made so many more books available. But because they dominate the market, publishers and big chains cut their throats to offer them discounts.”

This leaves independents in an impossible bind, unable to buy in bulk or sell competitively. The result is a boa-like constriction: an industry gradually running out of air. What is needed, Chris says, is something like the old Net Book Agreement, which fixed prices between publishers and sellers, and set prices at which books could be sold.

Its demise is not a new concern; the agreement held between 1900 and the 1990s, when it was abandoned by large chains. “It [the NBA] was outdated, yes. But if you want to save bookshops, you have to be supplying under the same terms as chains. It’s that simple. You have to have a level playing field.”

IT’S ALWAYS THE END OF THE WORLD

A few years ago, Amazon, not content with killing the bookshop, announced a plan to do away with publishing as well. They would do this by bypassing it altogether, and release books through its own publication lines. The New York Times quoted a source as saying “publishers are terrified and don’t know what to do”, but Amazon was unmoved.

“It’s always the end of the world,” Russell Grandinetti, one of its top executives, said. “You could set your watch on it arriving.” This is the remorseless logic of automation, the same now as it was in the 1800s. And in a sense, no one really has anything to complain about. People still get their books, and from the perspective of a $427bn conglomerate, the whole apparatus of agents, distributors and publishing houses looks like a lot of unnecessary machinery.

Booksellers tend to share some of Grandinetti’s scepticism about Amazon-mageddon. Fred Campbell, who works in the Children’s Bookshop in Muswell Hill, points to the fate of ebooks as instructive. “For a while there, yeah, everyone thought it was the end of the world,” he says.

And now look, after peaking at £275m in 2014, ebook sales went into precipitous decline, falling 17 per cent to £204m in 2016. When I ask Chris about this, he recounts a story of going to the London Book Fair five years ago, and seeing row upon row of Kindles. At the most recent Fair he attended, he says, there was hardly any mention of them at all.

“We’re on the way up again,” Mairi tells me. “Ebooks stagnating doesn’t just help chains – it applies to independents, too. When local bookshops started to decline, people started to miss them. And people are realising, having not bought books for a while, what it means to not have books on a bookshelf, that they can’t pass on that amazing book to a friend.”

You hear this sentiment repeated a lot: that a combination of ingrained public goodwill and the ineffable appeal of print will carry bookshops through. “The experience of reading is never going to change, really,” Campbell says, “There’s nothing extra you can add on to it, and there’s just something about turning a page that helps you get into that world.” He also cautions that children’s books are different, a protected class, because of the importance of colour and tactility. No one wants to read to their child off a Kindle.

Much more immediately imperilled, it seems to me, are places like Muswell Hill Bookshop, which has no such niche. It was a sister shop to Prospero’s, and stands opposite the Children’s Bookshop. The manager, Tim Robinson, used to run the Bookshop Islington Green, until a Borders opened up nearby and the costs became unmanageable.

“It was all very sudden,” he says. Muswell Hill Bookshop felt the pinch, too; it was forced to downsize, selling its second property (it’s now a pet shop) and much of its stock. “It’s been going OK since we decamped here,” Tim says, “but it’s still a struggle.” He’s also sorely aware of the demographics of his customer base: “Younger generations don’t go into physical bookshops so much. I’ve definitely noticed that our clientele is mainly older, and seems to become more so each year.”

Amazon isn’t a doomsday clock for bookselling, any more than it was for publishing. Indie bookshops will continue to muddle along, and the resurgence of print has given some in the industry renewed optimism. But it’s hard to know whether this is a bright new dawn or a temporary reprieve.

It’s also hard to shake the sense of a lost inheritance, and a noble but ailing civic mission. If the high street is where independents do their best work – “We recommend people things they’d never thought of reading,” as Tim puts it – then their vanishing from it represents a palpable loss.

“At least there used to be public libraries where people could go and read, but they’re going, too,”, Edwards says. “From a business point of view, this is just the future. It’s just what happens. From a cultural point of view, it’s a disaster.” He sighs again.