London Stock Exchange boss Julia Hoggett: We’ll fight for everything

The London Stock Exchange is the capital’s financial flagship – and it’s had a tough few years. The bourse’s boss Julia Hoggett tells Charlie Conchie why she’s confident she can turn it around

Julia Hoggett likes to think of her career as a series of exam questions.

Each stage has been weighed up and approached as a separate and solvable issue. Each has been tackled with all the tools and knowledge she’s built up in advance. And crucially, each has been ticked off in some way before turning the page to the next one.

Facing the London Stock Exchange chief now, though, is a real toughie; the sort that appears with an expanse of empty lines in front of it and a clock ticking ominously overhead.

“The exam question for now, is ‘how can you do everything you can to inject as much dynamism and life into the UK’s capital markets so they can serve both the UK economy and the UK as a global financial centre’,” she tells City A.M. in an interview at the London Stock Exchange.

Looking at life as a series of exams might seem arduous to some. For Hoggett, who didn’t get to her position by flunking many of the papers in front of her, it is a neat way of succeeding.

But Hoggett has by any measure faced a trickier test than ever this year. Initial public offerings have tumbled sharply against a torrid global backdrop, the year’s blockbuster listing of Arm escaped her grasp and a steady stream of barbs have been thrown by companies lamenting the staid conservatism of London.

Behind the headlines of ‘boost’ and ‘blow’ to the City, she is insistent the job of reform is well underway. But even Hoggett concedes this particular question is proving a “big one”.

Full marks

Hoggett’s career in the City began as a practical way to answer one of those questions. The daughter of former president of the Supreme Court Baroness Hale, she took an unexpected pivot towards the Square Mile after hitting what she saw as the constraints of a career in the libraries of Cambridge.

“I read social political sciences at university and wound up specialising in sociology in sub-Saharan East Africa – I would have been voted least likely to go into the City at the end of my undergraduate”, she says.

It was after a trip to Malawi to help tackle an energy crisis that the idea of a career in banking began to take shape.

“I ranted one evening to my father about how I was ever going to answer this exam question sitting in the stacks in Cambridge. He responded by saying ‘you won’t’,” she recalls.

Our listing rules have worked very well for companies that have had fixed assets that have thrown off cash, where past performance is a good indicator of future performance. They have not been as well built for intellectual property-based companies where the value is in the opportunity of the future.

LSEG chief Julia Hoggett

The advice instead was to apply to investment banks that cover emerging markets, where she would “learn more about how developing countries operate in the global economy in two years than [she] ever would sitting in the stacks at Cambridge’”.

Hoggett’s career in the City was born. She joined JP Morgan – “I chose JP” (the offers were not in short supply) – to try and paint a more in-depth and practical picture of helping the developing world. But even then, the plan was a short knowledge-gathering jaunt before returning to put it to use in the library.

“In the milk round interview I had with JP Morgan, the first question asked was ‘with your academic record, what’s to say you’re not going to take everything you can for two years and then go back and finish your PhD?’

“Secretly, I thought that’s a really good question, because that’s my plan.”

Instead, Hoggett said she’d like a job that is “endlessly fascinating, endlessly changeable and endlessly difficult”, and if the role delivered, she would stay for “as long as it remains so”. So it has transpired.

Since then she has bounced around every corner of the banking sector, flipping from Dublin-based Depfa Bank to Bank of America before swapping her role to join the Financial Conduct Authority as head of the investment banking unit and then director of market oversight.

It was almost by accident she then ended up as head of London’s historic bourse. In an oft told story, on the night that Apple’s market capitalisation surpassed that of the entire FTSE 100, she sat down to write a list of things that needed to be done to fix the malaise gripping the UK’s capital markets.

The next evening, the phone rang.

“Why haven’t you applied for the LSE job?,” said the headhunter on the line. Her next exam question began to take shape.

Reform agenda

That capital markets to-do list has been growing ever longer since Hoggett took the reins in April 2021.

Then, the IPO market was going gangbusters with pent up pandemic demand as London hosted some £9.4bn of floats in the first six months of the year alone. But that year-long IPO frenzy proved something like a final shroud to the deeper structural issues now consuming Hoggett’s role.

Last July, she gathered a crack squad of City grandees called the Capital Markets Industry Taskforce, including Schroders chief Peter Harrison and GSK chair Sir Jonathan Symonds, to try and drag London’s markets into the twenty-first century. The group has adopted something like a think-tank mentality, pressing ministers and regulators for reform to get money flowing back into the stock market.

“Our listing rules have worked very well for companies that have had fixed assets that have thrown off cash, where past performance is a good indicator of future performance,” says Hoggett.

“They have not been as well built for intellectual property-based companies where the value is in the opportunity of the future.”

The troubles facing the market have played out in the numbers this year. Just 18 firms raised £650m in the first six months of the year, a slump of 30 per cent on the first half of a torrid 2022 which saw just £1.6bn raised in total.

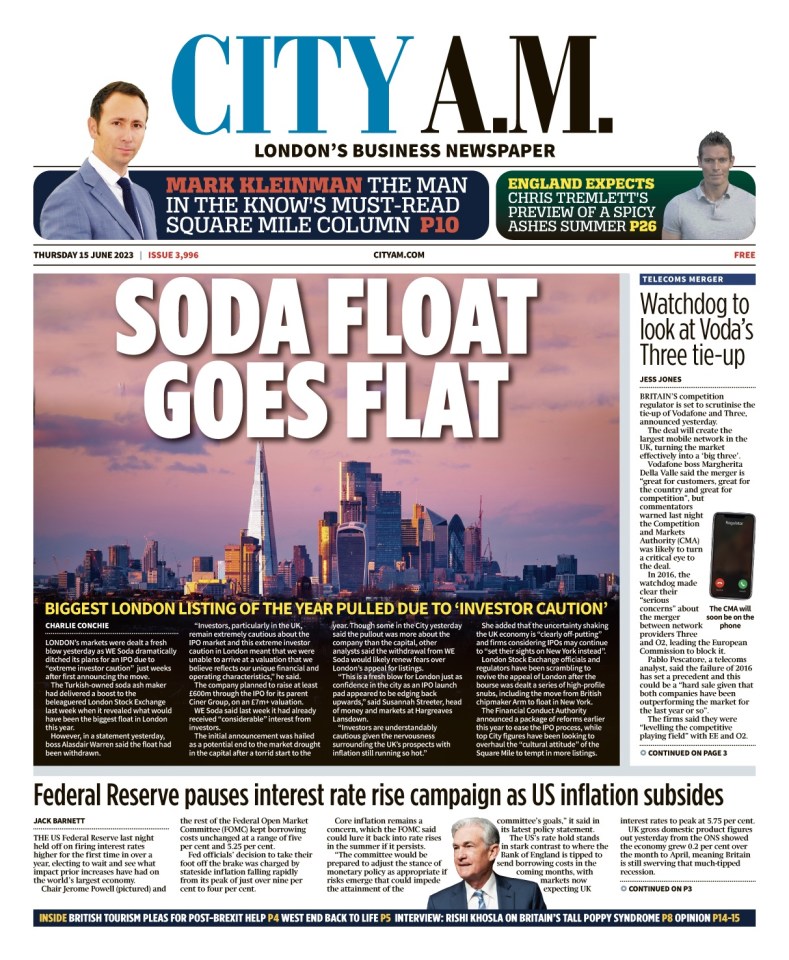

Salt in the wound has been sprinkled by the likes of Turkish soda ash firm WE Soda, which plotted a move onto the public markets in June before abandoning it weeks later with a round of attacks levelled at the “extreme investor caution” of London.

Like a glove

Hoggett says a “five fingered glove” of reform is now needed to grip the market and shake it back to life.

Primary and secondary market reform make up one of the fingers, the depth of investment research, the flow of domestic risk capital in the UK, corporate governance and finally the overarching and more ethereal “ecosystem for scaling consequential private companies” make up the rest.

Most of those areas are “in very good shape and progressing”, she claims. The government-commissioned Hill Review and Austin Review tabled a number of reforms and the FCA has pushed ahead with changes, including rolling out dual class share structures and merging the standard and premium segments of the main market.

The Kent Review published in July has also looked to revive the quality and depth of investment research after it was hammered by EU rules in the wake of the financial crisis.

Pension cash though has attracted most of her attention in the past 18 months. Her band of grandees are looking to unlock billions of pounds stashed away in the country’s retirement pots which has flowed out of the stock market and into safer income producing bond holdings over the past 23 years.

“I think the reality is that we have we turned our defined benefit pension schemes effectively into savings schemes and risk-off schemes, for understandable reasons,” she says.

“But then we applied that same language to our [newer] defined contribution schemes which are the biggest single investment pot anybody has – not savings.”

The efforts may have moved in something like the right direction this year as a group of top pension and insurance firms agreed to begin channelling their cash into private UK companies. On the public markets though, the efforts are yet to bear meaningful fruit.

Doom and gloom

Even so, it is perhaps the fifth more immaterial idea that is proving the hardest nut to crack.

While the FCA pushes on and both political parties lean into reform – the efforts have “cross-party consensus”, she says – Hoggett’s frustration at the vibe surrounding the UK’s capital markets is palpable.

“People have narratives in their heads and are looking for things to fulfil it rather than anything else,” she says pointedly at the beginning of the interview.

Capital markets groups have begun to point to the negativity and the media in the UK as one of the key reasons for firms to shun it as a destination.

A report from industry body UK Finance earlier this year found the “perception of the approach and attitude of the media had an oversized influence when considering whether to join the UK markets”, with some companies saying their approach was to join the UK in ‘stealth mode’ to “avoid the news cycle and potential negative public sentiment.”

Hoggett’s comments signal something like an invisible sixth finger in her glove of capital markets reform. Central to solving the problem is fixing the narrative, and at the heart of that seems to be a looming struggle with the press.

“We live in a country of the free press – the media’s got a right to report what they want to report, but I think it’s fair to say that quite often the context is missing,” she adds.

“Where we actually sit in terms of being by any measure the largest in Europe, and consistently so and still so[…] is not your starting point in a lot of the narrative.”

In its latest review, CMIT commissioned the boss of L&G Sir Nigel Wilson to conduct a holistic review of London’s “market model”. A central part of that will be resetting the doom and gloom “narrative” hanging over London.

London Stock exchange loses its Arm wrestle

Never has that narrative crystallised more brutally however than in the fight to win the listing of British chipmaker Arm. The battle played out nationally as a symbolic struggle for homegrown technology which the UK has so often lost across the Atlantic.

Despite a monumental government-led lobbying effort, Cambridge-based Arm committed to New York in what is expected to be a $60-70bn valuation float and the biggest of the year.

“It was a blow to the UK,” she admits.

“We felt we had a very strong case, and we still do, and we will keep pushing.”

The FCA’s restrictive rules on reporting were in part blamed for the snub, with onerous requirements on third-party transactions among the main concern, the Financial TImes reported.

“It was down to some technical reasons in the end. A lot of which the FCA is now addressing,” she says.

While the uproar and press furore has clearly been unwelcome, she concedes that the strength of feeling is a good thing.

Hoggett says she and her colleagues on Paternoster Square are now not willing to not let any listings slip out of their hands before they make their case.

“We should fight for every listing that we think there is a strong UK proposition for. And we shouldn’t be shy about saying it,” she says.

“We won’t win all of them, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t fight. And as long as I’m doing this job we will.”

Pens down?

While the headlines of boost and bust are often bruising, inside the London Stock Exchange the mood is more serene.

The bourse’s debt market is still the second largest in the world and as part of its reform efforts it is branching out into new arenas, including a new private stock exchange slated for launch next year.

She says reform, rather than signalling panic, is a natural evolution.

“We’ve been here for 300 years. Our job is to be here for another 300 plus years,” she says.

“Our job is to be the provider of the fundamental infrastructure that the market needs, and to adapt and change how the infrastructure operates according to the needs of the market.”

While she might like to hear ‘pens down’ on this test, Hoggett knows she is far from turning the page any time soon.

“This is sort of GCSEs, A-levels and a degree all rolled into one,” she adds

“I think this has got a fair slug of time to go.”