Let’s be honest, nationalising the water companies would mean even higher bills

Even if we want to punish water firm bosses for letting sewage and faeces end up in our oceans, nationalisation will only give us higher bills, writes Matthew Lesh

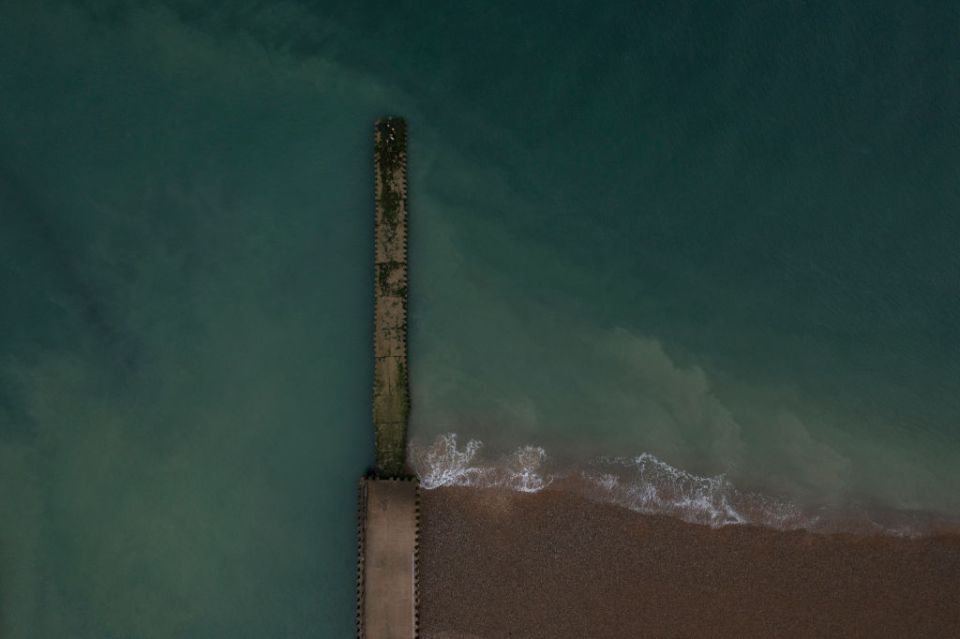

There are few more revolting images than human faeces streaming into Britain’s rivers and seas. Not just the stench, but also environmental damage and closed beaches. The ongoing sewage debacle has driven righteous anger with Britain’s privatised water companies and the imposition of large fines.

But the situation may not be so simple. These “storm overflows” prevent an even worse fate during heavy downpours: poo flowing back into people’s homes and onto streets. It’s also not easy to solve. Increasing the treatment capacity in Britain’s Victorian-era sewage system will cost tens of billions of pounds, ultimately paid through higher consumer bills.

There are no easy solutions for Britain’s embattled water and sewage providers, just trade-offs and open questions. This is particularly true for Thames Water, which has been staring down the barrel of renationalisation after recent financial woes. Industry critics claim Thames Water and its ilk have taken out huge debts and provided generous returns to shareholders while dumping sewage and failing to address leakage. Thus, they argue, the entire privatised model is broken and should be reversed.

Indeed, water is a quintessential “natural monopoly”: an industry that is only efficient for a single provider (it doesn’t make much sense to have multiple pipes running to every household). Accordingly, the usual competitive dynamics that improve services and push down prices do not exist. It is easy for companies to take advantage.

But a state takeover is far from a panacea. It would not only be extremely expensive – either costing up to £90bn or requiring expropriating assets and turning the UK into a banana republic – while doing little to fix the underlying challenges.

The water industry requires investment, but there’s little reason to believe that our cash-strapped government would provide the necessary capital injection. We know this tendency from the experience before privatisation: decades of underinvestment, poor water quality and polluted rivers and beaches. Politicians tend to prioritise health and pension spending today over longer-term infrastructure investments.

By contrast, £160bn has been invested in water since privatisation. Two-thirds of beaches are now classed as excellent (up from less than one-third) and wildlife has returned to rivers that were once considered “biologically dead”. Meanwhile, water bills are lower in real terms than a decade ago.

Globally, studies indicate that privatised water provision provides significant environmental, public health and economic benefits. This is because private providers are incentivised to improve efficiency – unlike politicians and bureaucrats – so much so that they can make a profit, lower bills and invest in the system.

The challenge is ensuring private companies act in the broader public interest. This means carefully specifying requirements, incentives and oversight. In the UK, this role is handed to Ofwat – who have largely allowed financial shenanigans to go unchecked. But there’s no reason to believe an entirely nationalised system would be any better. There would be nobody to hold the bureaucratic managers accountable, along with a lessened ability to tap private markets for investment.

Professor Steve Hanke of John Hopkins University, who has been studying water management since the 1960s, has called for the UK to adopt the French-style franchising model. This means competitive auctioning off the right to provide water services at regular intervals, with well-specified contracts and careful oversight.

The French model may be hard to replicate – as it depends on competent state oversight, which seems to be lacking in the UK government. Nevertheless, the idea of a “back to the future” return of state control is only likely to result in higher bills and a dirtier environment.