Let’s all hand our cash over to the Treasury to pay off UK’s £2.5 trillion debt pile (not)

Here’s a fun fact.

If everyone in the UK worked for a year and gave all their earnings to the Treasury, the government could nearly repay the country’s more than £2.5 trillion debt pile.

Alright, that’s oversimplifying the equation. But it does illustrate a principle in economics that often gets lost in the deluge of headlines warning of the UK’s unsustainable debt stock.

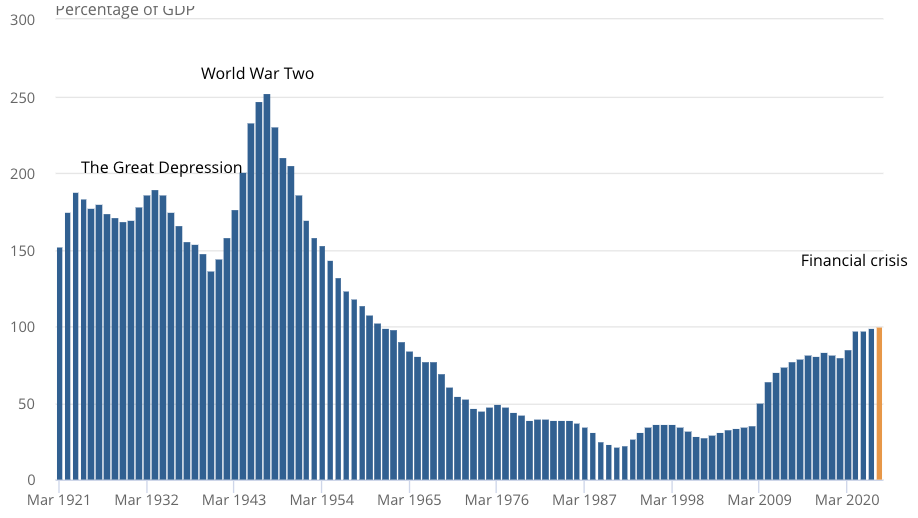

In econ jargon, its debt-to-GDP ratio has topped 100 per cent – the first time that threshold has been breached since 1961.

The rate of change in that figure over the last 15 years has been staggering. Between the late 1980s and late 2000s, it barely moved away from 35 per cent or so.

In 2009, after the government stepped in to save the UK’s largest banks and was in the process of stepping up welfare payments amid the ensuing economic downturn, it leapt to more than 50 per cent.

Since then, it has doubled. You’d be hard pressed to find another leading economic indicator that has undergone such a huge rate of change in such a small amount of time.

It is also a reflection of the turbulence that has buffeted the UK economy over the same period.

Banking bailouts drained the Treasury’s coffers, as did the support packages to prevent a decline in activity following the retrenchment of lenders during the credit crunch.

Even now, Brexit has yet to deliver the promised benefits to household living standards and trade.

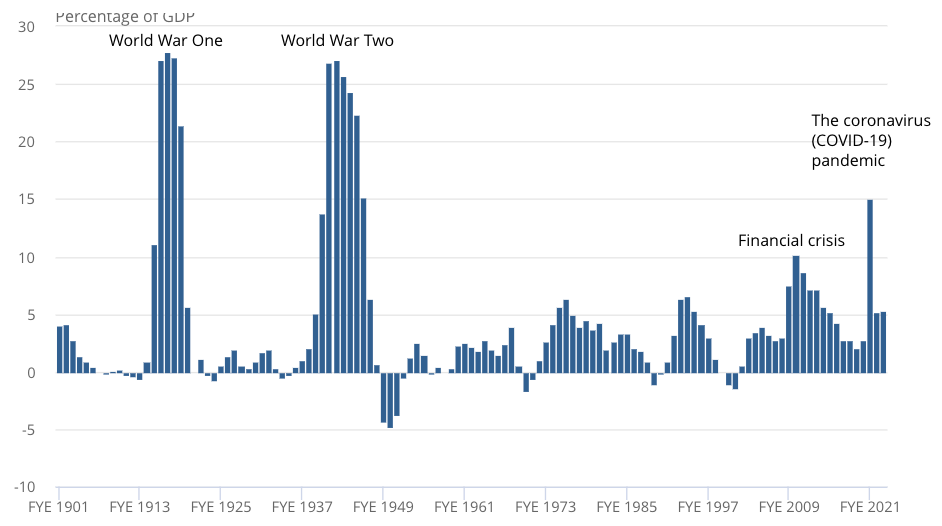

And the Covid-19 pandemic engineered the biggest fall in GDP since the Great Depression (maybe even longer). Emergency measures such as the furlough scheme turbocharged government spending at a time of nosediving tax revenues.

UK’s debt pile has risen sharply…

Last year’s energy crisis again forced lawmakers to intervene to avert a living standards catastrophe.

The sum total of these economic shocks and necessary government responses has been to force borrowing and, consequently, debt sharply higher.

But it’s not the stock that we should be worrying about. Instead, according to traditional economic thought, it’s whether the economy is growing at a slower rate than the debt pile (subscribers to modern monetary theory would contest that claim).

According to the ONS’s estimates (which are often revised), that is what’s happening right now.

All signs point to sustained pressure on the public finances in the coming years, initially emanating from the much higher interest rates the government is servicing on its debt.

A big chunk of the UK’s liabilities are tied to the retail price index, an old measure of inflation that has jumped over the last year or so. This, compounded by the Bank of England raising official borrowing costs quickly and steeply, is poised to send “central government debt interest costs to well over £100bn a year all the way through the next five years,” according to Sanjay Raja, a senior economist at Deutsche Bank.

“The looming additional burdens linked to ageing populations, the green transition and geopolitical tensions complicate the picture further” over the long term, the Bank for International Settlements said in its annual report over the weekend.

Crimped public finances present the greatest risk to the Conservatives losing the next general election, which must be held by January 2025 at the latest, though it’ll probably be in the autumn of 2024.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak are certain to try to reach for tax cuts to win over voters. Given their commitment to fiscal balance, spending cuts would likely countenance such a move.

… as has the yearly deficit

Hunt was estimated by the Office for Budget Responsibility in March to have the slimmest headroom of any Chancellor against his fiscal rules since 2010.

Pressures on the public finances since those calculations have actually amplified, limiting his space to loosen policy further.

Labour faces a similar bind, and Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves recently watered down a commitment to spend £28bn a year on renewable energy as her plans rubbed up against fiscal reality.

Expect both parties to table a pretty unambitious economic agenda during the election campaign. Right now, that is the exact opposite of what Britain needs to reverse its economic fortunes.

WHAT I’M READING

Diverging from the mean here. A break from the usual wrap of an interesting piece of research published recently. I’ve just picked up Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita for the first time since my late teens for a second read. If you haven’t thumbed through it before, then take a break from the daily grind of bond yields, inflation and interest rates and put it straight to the top of your summer reading list. You won’t regret it. Back to form next week.