Labour must address long-term sickness to get the economy growing

The UK has a serious problem. For the first time in decades, the health of the workforce is a major barrier to economic growth.

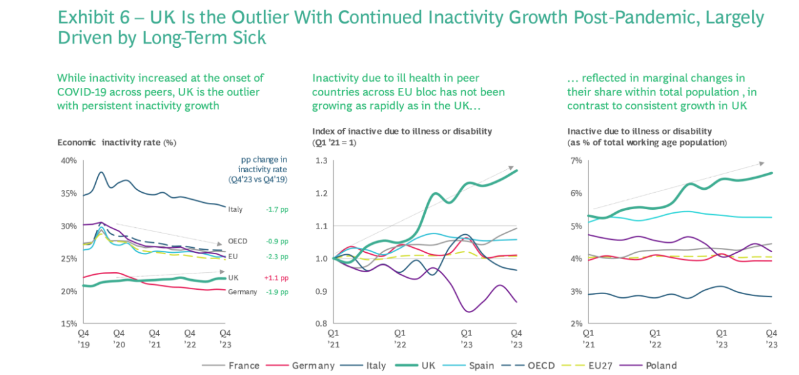

Since the pandemic, an extra 900,000 people have fallen out of the workforce due to long-term sickness.

The deterioration in health since the pandemic makes the UK an outlier among rich economies. It is the only G7 economy where the participation rate has not recovered to its pre-pandemic average.

If the new government is serious about its pledge to boost economic growth, it must address the worrying increase in long-term sickness.

A report from BCG and the NHS Confederation estimates that reintegrating between half and three-quarters of those who have dropped out of the workforce since 2020 could unlock £35-57bn in revenue for the state over the next five years.

The boost to growth would be substantial too, with GDP forecast to be three per cent higher by 2029 as a result.

Consider those numbers in comparison to the figures which could be raised from even a fairly major tax increase, such as equalising capital gains tax and income tax. According to a report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), such a measure could raise £16.7bn, but the wider impact on growth is ambiguous.

As the report notes, “the fiscal and economic benefits of tackling some of the structural economic and health challenges facing the UK are likely to deliver larger benefits than tinkering with fiscal policy”.

The extra piece of good news is that there are some reasons to think it should be a relatively easy issue to address.

The rise in long-term sickness has been a recent trend (as far as economic trends go). During the 2010s, the UK’s employment rate rose steadily and was actually at record levels on the eve of the pandemic.

BCG’s report suggests that many who are currently inactive due to ill health moved directly from paid employment, rather than a long-period of unemployment.

Traditionally, re-integrating people into the workforce is difficult if they have lost employable skills, but that task is made easier if they were in employment more recently. This means it should be easier to address than some of the UK’s other structural issues, such as low business investment.

Acknowledging the problem is the first step towards solving it, which was always a problem for the previous government.

The data suggests that musculoskeletal (MSK) and mental health issues account for around half of all those reported by the long-term sick, with mental health issues particularly prevalent among the young.

Conservative ministers preferred to blame the increase in long-term sickness – particularly its mental health component – on wokery.

While this made a more compelling election pitch – rather than admitting they had presided over a general deterioration in the quality of public health – it did little to address the issues at play.

The second step is to realise that improving public health relies on much more than just a functioning health service.

Since the Marmot report back in 2010, health policy experts have been interested in the social determinants of health.

These wider factors – which include things like housing, lifestyle choices and employment status – play a bigger role in determining health outcomes than narrow clinical factors.

Interestingly, of all the wider determinants of health, BCG’s report finds that economic and working conditions play the biggest role in explaining the variance in health outcomes across England over the past seven years.

“Investing in tackling wider determinations could have more impact on health outcomes than investment in behavioural factors,” BCG’s report notes.

Labour’s ‘mission-driven approach’ should be well-suited for tackling this problem, given its self-conscious attempt to get different government departments pulling in the same direction.

The new government has already made some positive moves, particularly by getting Jobcentres to focus more on providing career advice than on monitoring benefit claims.

There are a whole series of reforms recommended to help deliver the sort of change needed, including joined-up funding and resources for relevant departments as well as the creation of a dedicated team within the civil service to work on the issue.

But the reforms asked for in BCG’s report will require money – something the Labour government has signalled it is not going to easily part with.

Whatever Reeves and Starmer decide, this is one of the few issues that could make a meaningful difference to economic growth. They must get it right.