Jerusalem review: Mark Rylance proves he is the leading actor of a generation in juggernaut play

After Jerusalem premiered at the Royal Court in 2009 it began to generate a reputation as the greatest play of the 21st century. It’s hard to do justice to the level of prestige which has surrounded the show since; within theatre circles it is untouchable and nothing since – at least, no plays – have conjured anything like its level of hype.

It was arguably Mark Rylance’s breakthrough moment and in the years since, his Hollywood career owes a big debt to the show, which won him the best actor gongs at the Olivier and Tony Awards in 2010 and 2011.

In short, opening ten years after the original West End production closed, the play continues to justify its reputation as a modern day epic. Most obviously, it spans three parts, each around an hour, with its ambitious scope making it feel something like a classic Greek play, or a Shakespeare, and like those, it deals with broad themes about humanity. It’s not only the form but the sense it conveys of a faded England, of course loaded with new meaning in the years since its premiere, which justifies its status.

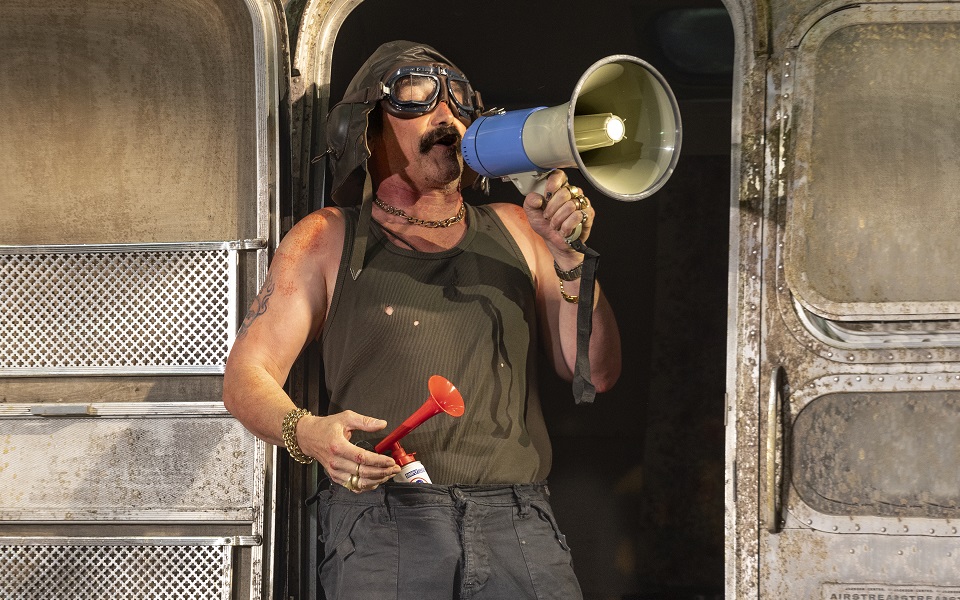

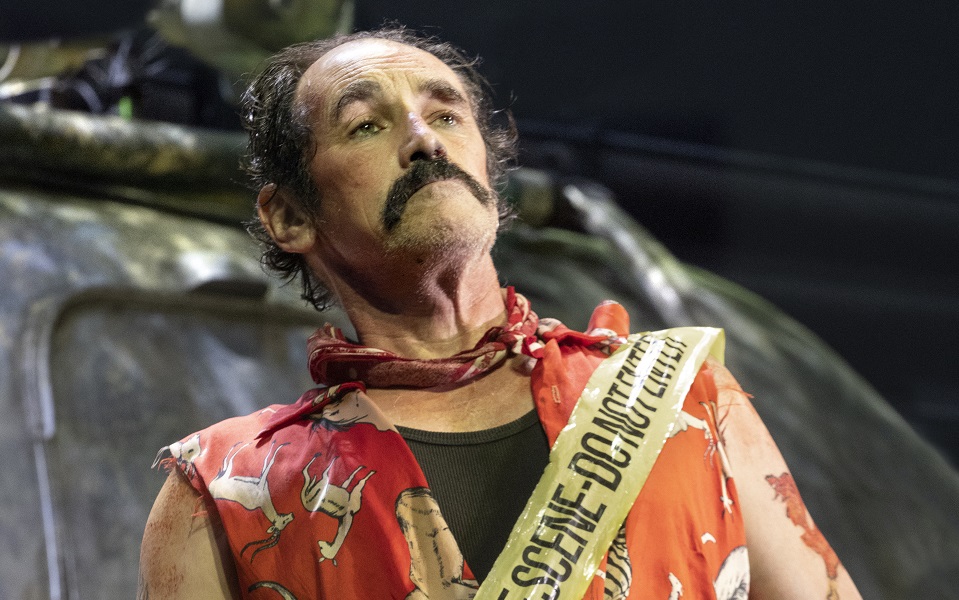

Johnny ‘Rooster’ Byron lives in a caravan in the woods in the south-west of England. There’s a new housing estate nearby, and council officials are threatening eviction. He’s middle aged and has a drinking problem, but he’s also supremely athletic. (Any doubts Rylance could pick up where he left off with this role a decade later are put to bed in the first 60 seconds when he neatly handstands off an animal’s drinking trough, completely submerging his head in water while balancing upside down.) Rooster’s lifestyle attracts the company of local teenagers, who hang out hedonistically and party with him and his mate Ginger, in a role reprised by Mackenzie Crook.

There’s a gorgeously verdant set with light streaming down through what look like real trees. It doesn’t just look authentically enough like a forest to get lost in, the set also enables the play’s more mythical, abstract storytelling. Think of the magical forest in Much Ado About Nothing and you’ll have some idea of the tone.

It’s a mistake to try to understand one linear version of Jerusalem. Jez Butterworth’s text feels purposefully designed for multiple readings, and Ian Rickson’s chaotic direction matches Butterworth’s imaginative text by jolting the audience in and out of an England we recognise, to imagined realities that are more nebulous and abstract.

I read Jerusalem as a play about disillusionment. A comment on ideals of Englishness, as well as notions of the English countryside, how those play with identity and a sense of self. The day is St George’s Day, and the local Flintlock fete is underway. Sometimes, it can be heard in the distance. Rooster will be evicted the following morning, but he’s more interested in carrying on the party, and regaling his troupe with far-fetched tales.

Rooster, to me, feels less like Butterworth and Rylance have sketched an individual man but a raging, broad-brush symbol of outsider status – both mentally and physically adrift. With the role, Rylance shows off how he’s become one of the nation’s most prized contemporary actors with a mind-bendingly expansive performance. At one moment Rooster is leering and intimidating, scowling at his comrades with unpleasantly exaggerated hyper-machismo. At others, he’s a funny and loveable storyteller whose misery is distracted by the attention he receives from the young set who hang out with him (and later laugh at him behind his back). He’s purposefully abstract, performing the scars of a thousand different disillusioned men.

In the second act he tells a gorgeously bonkers story about a 80-foot-high giant he came into contact with traversing the west country. They met somewhere near the A14, says Rooster, and sat down, he must have been 45 feet. Rylance plays Rooster with the suggestion he really believes in these beings, and he’s only sometimes taking tabs of acid. He performs with wide eyes big enough that we, too, are carried along with the story – he’s so dynamic, he gives off the impression he could adapt the performance every night and bring something new.

It’s mostly utterly captivating and the action crescendos in the way a classical play might, with a violent and tragic clash so palpable there was a nervous feeling in the audience – as if we were watching something real unfold. Only once, midway through the second act, does this juggernaut lose pace for fifteen minutes or so. Mostly, Jez Butterworth’s writing is masterful, sustaining big laughs as well as horror as Rooster’s situation becomes increasingly dystopian. It’s astonishing how Jerusalem manages to feel in parts like a horror and also like The Vicar of Dibley.

The elephant in the room is that in the years since Jerusalem was last staged Brexit has redefined all of our conversations around national identity. It still feels like the play’s main purpose is to examine what it means to be an outsider in the broadest possible terms, but as far-right groups are increasingly pervasive, the programme’s reciting of the ‘England’s green and pleasant land’ message from William Blake’s poem feels naturally loaded. The divide between those in the houses and those living in the forest is hard to ignore as a metaphor for the void between the Remainers and those who voted Leave.

It doesn’t overshadow what remains an astonishing piece of theatre. Not so much asking why, but showing how, it’s tonally absurd but deftly effective creativity. I can imagine no one embodying Rooster but Rylance who – jumping up and down at the curtain call to shake off euphoric levels of dopamine – is mesmerising. Beyond the politics, what’s most important is getting lost in Butterworth’s meanderingly hypnotic monologues and Rylance’s rhythmic, lumbering gait as he heaves enthrallingly about the stage in a performance which proves he’s the leading actor of a generation.

Jerusalem plays at the Apollo Theatre until August 7