Jeremy Hunt’s fiscal rules are holding back the UK economy – it’s time for change

Bean counters are running the Treasury again.

I’m imagining sheets of paper plastered with Jeremy Hunt’s current fiscal rules pinned up around Whitehall to remind departments of the belt-tightening needed to balance the books.

Fiscal rules are targets Chancellors have aimed to meet since George Osborne pivoted away from Gordon Brown’s “Golden Rules” in 2010 after the financial crisis wreaked havoc on the public finances.

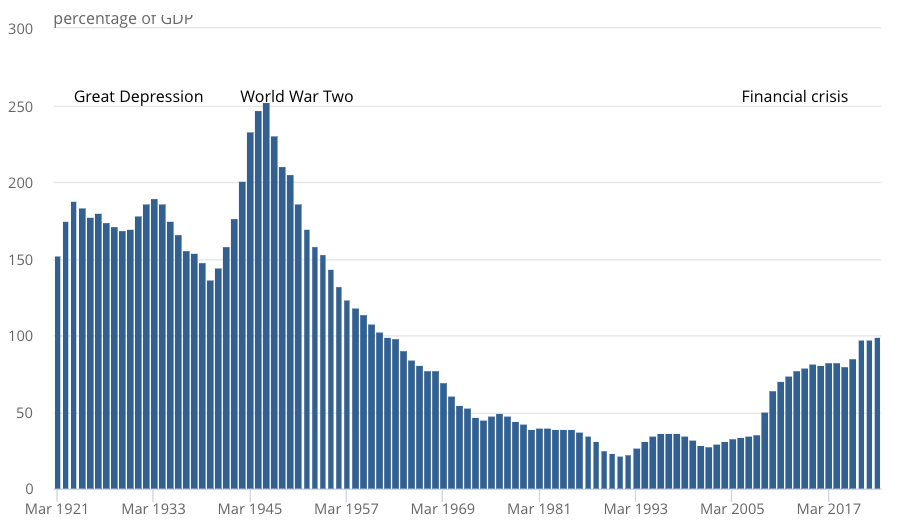

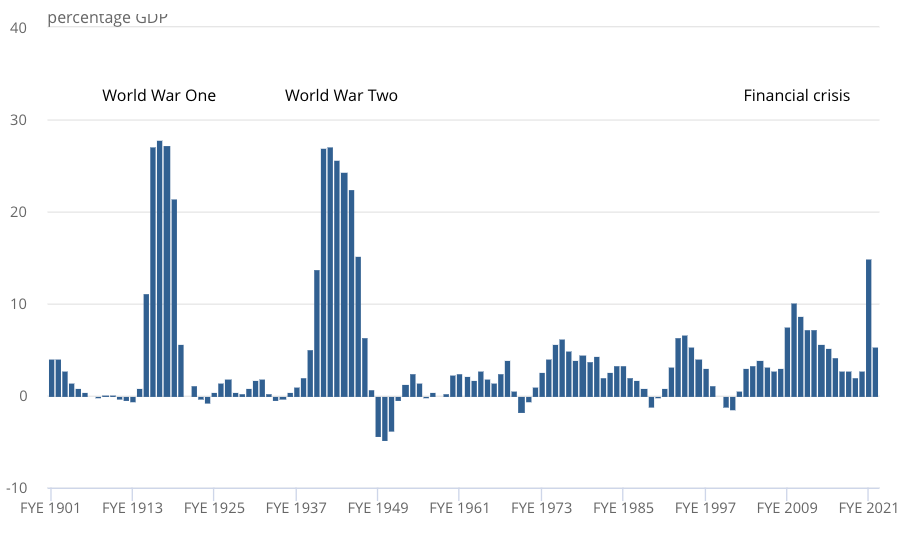

They often include some mixture of driving down the debt stock as a proportion of the economy and yearly borrowing.

Hunt’s current targets are to have the debt to GDP ratio falling and make sure borrowing does not exceed three per cent of GDP in five years

Sources at the Office for Budget Responsibility have told City A.M. the last Chancellor to actually hit their goals was Philip Hammond, Theresa May’s money man.

The intention of placing a restraint on the government’s purse strings is to convince global investors of “the UK’s ability to pay back its debt and thus offer favourable borrowing conditions,” according to the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) think tank.

Breaching those parameters can have disastrous consequences for the UK economy, as we saw with the aftershock of Liz Truss’s mini budget that ricocheted through international financial markets.

Government spending and tax rules were actually a lot tighter when Truss signed off on £45bn of unfunded tax cuts back in September last year, meaning she and then Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng were even further away from hitting them.

The adverse market reaction to that historic fiscal event was likely triggered by two things.

UK’s debt stock as a share of GDP has ballooned of late…

First, and by far the largest factor, inflation was in the double digits, mainly because the economy was running way too hot and suffering from an external energy shock caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

We were operating at what economists call ‘above our potential’, putting upward pressure on prices.

Stimulating the economy with tax cuts risked pushing inflation and expectations of future inflation higher, prompting the Bank of England to hike interest rates aggressively.

Investors priced in that higher-than-expected rate path by selling government bonds, pushing yields higher. The pair move inversely.

Rapidly rising prices keep a lid on what the government can do to support households and businesses. Jeremy Hunt recognised this and ditched nearly all of Truss’s measures and launched a further £55bn of tightening in November.

But what happens after inflation is tamed? Bar another big economic shock, it seemingly is on a downward path this year after figures last week showed it dropped for the third straight month to 10.1 per cent.

In and of themselves, fiscal rules basically mean nothing for a country’s public finances. The real constraint is inflation and whether boosting spending or cutting taxes will release the inflation tiger from its cage.

In fact, some corners of the economics profession argue our dogmatic approach to hitting fiscal rules has been a primary factor weighing on economic growth since the financial crisis.

“There is no satisfactory definition of the objective of fiscal policy that meets a social welfare objective,” the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) has argued.

Persistently trying to just reduce the debt stock has shut off routes to launching policy that can boost growth powered by productivity improvements, the holy grail for any economy.

… pushed higher by a wide deficit

“If public borrowing is ‘spent’ on things that have a high chance of increasing GDP growth, such as public investment, then this will be much better for public finances than spending it on things that are unlikely to improve economic performance substantially… It is thus crucial that fiscal rules do not prevent governments from borrowing to invest,” the IPPR has said.

Critics of too much government interference in an economy argue it risks pushing interest rates higher by increasing debt supply and curtails dynamism and innovation, two factors that are needed to raise productivity growth.

However, any type of investment, all else equal, will expand a country’s capacity to make things, raising the chances of clinching growth that does not ignite price rises.

Politicians tend to chop and change their promises to tweak the economy because they try to catch the wind of voter intention. While those choices help lawmakers win elections, they can be a roadblock to social progress.

“The sad but obvious fact is that the demands of the economy cannot be folded into political horizons,” Jagjit Chadha, the NIESR’s chief, has said.

Since their modern day inception in 2010, the UK’s fiscal rules have changed pretty much every year.

Notwithstanding their arbitrary nature, fiscal rules are a set of targets trying to contain an economy – an ever-changing organism – which typically leaves government tax and spending policy wanting.

What we need now is a dynamic set of targets that focuses on raising living standards, not a return to “budgetarianism” that simply balances the books.

WHAT I’M READING

Survey data has been overstating just how weak the European economy is at the moment, analysts at investment bank Nomura. “Our survey-of-surveys measure suggested euro area GDP growth would be -0.1 per cent q-o-q in Q3 2022 and -0.3 per cent q-o-q in Q4 2022. Official data, meanwhile, held up far better. Q3 2022 GDP growth was actually +0.3 per cent q-o-q, as a result of stronger household consumption and fixed investment than many expected,” they said in a note last week.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

Brits’ pounds aren’t stretching as far as they used to. The value of retail sales in January was 14 per cent higher than in February 2020 despite sales volumes falling more than one per cent, the Office for National Statistics said last Friday. The figures illustrate families are having to spend more on each product they buy. Inflation has eroded the value of pay increases over the last year, prompting economists last week to warn January’s 0.5 per cent sale volume rise is unlikely to carry on through the first half of this year.