It’s time to move away from burning wood pellets for our energy needs

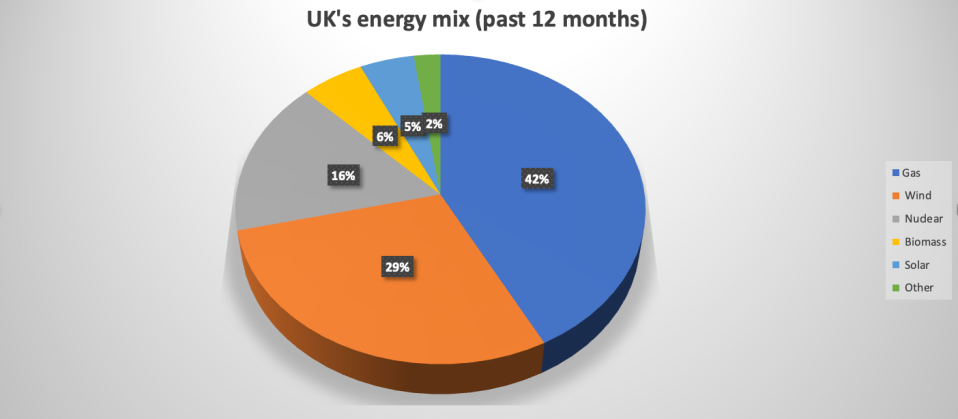

Over the past 12 months, nearly five per cent of the UK’s energy needs have been met through burning wood pellets.

Now that the UK has shifted from coal power and is looking for a long-term future beyond gas through ramping up increasingly sophisticated clean energy technology, such a rudimentary power source seems surprising.

Yet, biomass energy counts as 12 per cent of the country’s renewable mix and is a key feature in the government’s drive to net zero and supply security following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The chief source of domestic biomass is Drax Power Station – the largest facility of its kind in the UK – where pellets are imported from across the world to Selby, Yorkshire, and then treated for burning at one of the plant’s four large-scale boilers.

Hooked up to the grid, the 3.9GW plant has played a vital role in keeping Britain’s lights on and boilers running amid a Russian supply squeeze on the continent this winter.

Not that this is an act of charity, as Drax has raked in monster profits from the energy price crisis, with earnings up 84 per cent last year to £731m

So far, the site has received £6bn in taxpayer subsidies, including £800m in public funds in 2022 to support biomass energy.

It is also highly likely to feature in the country’s biomass strategy, expected to be published between June and April this year as the government scrambles to bolster the country’s energy independence.

Yet, the government has an increasingly difficult juggling act of balancing supply security with emissions – as the energy source is now at the centre of a number controversies and critical evaluations from the industry.

Drax or decarbonise, warns CCC

A damning report from influential advisory group, the Climate Change Committee, was published last week – warning the UK is in danger of missing its goal of decarbonising the grid by 2035.

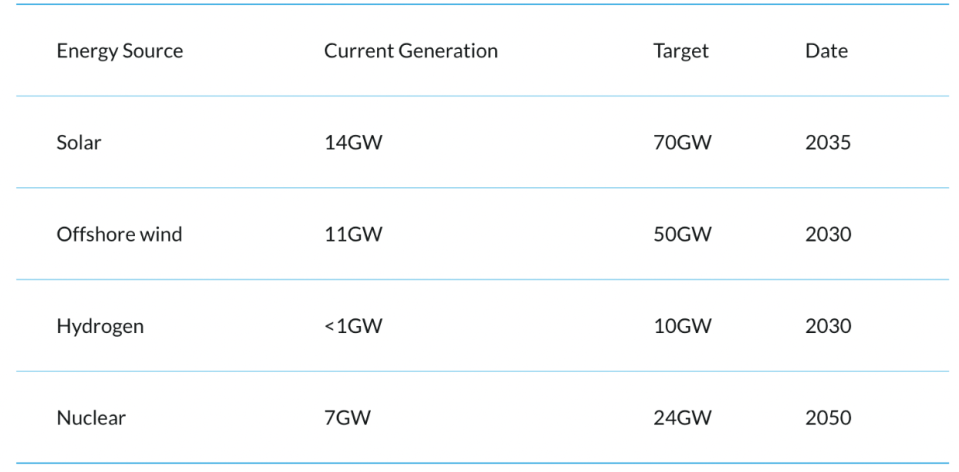

This an essential milestone in its push for net zero and its wider climate and energy security goals, which requires a vast ramp-up in transmission infrastructure, renewable power and electrification.

The CCC argued that to boost the UK’s green efforts, the government should stop the flow of multimillion pound subsidies to companies that burn trees by 2027.

Instead, the UK should ditch biomass energy in its current form by the end of the decade.

It believed the energy source is too expensive and “even sustainable biomass supplies have significant lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions.”

Dr David Joffe, the CCC’s head of net zero, later told reporters biomass is “not good value for money for bill-payers, and it’s not the right thing for the climate either.”

He also warned biomass producers are being overused, and that they “run for as many hours as possible rather than operating flexibly in a back-up role” because they are paid the wholesale price, which is linked to gas prices, alongside subsidies.

Drax has been under sustained scrutiny for its emissions, with the power group revealing in its accounts in 2021 that it was responsible 13.3 megatonnes of carbon dioxide through its operations.

Sky News’ calculations suggest Drax’s Selby plant is the largest CO2 emitter in the UK, before any carbon dioxide removal by new tree growth has been factored in.

This is not a surprise when burning wood produces more greenhouse gases than burning coal – the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel.

Drax was accused last year of logging wood from old, carbon rich forests in Canada in a BBC Panorama investigation.

This has been exposed with satellite images showing old-growth forests being sawn down on land belonging to Drax.

Drax denies the claim, and has offered to begin undertaking a carbon analysis of all its wood imports for its biomass facilities.

Yet, such questions over its practices undermine confidence in the energy source, and suggest biomass may have reached its natural shelf life in the UK’s energy mix.

Energy priorities should lie elsewhere

Biomass energy is considered renewable by DEFRA because new trees are planted to replace old ones used in sourcing wood.

These new trees are expected to recapture the carbon emitted by burning the pellets.

When used in high-efficiency wood pellet stoves and boilers, biomass pellets can offer combustion efficiency as high as 85 per cent – making it highly prolific as an energy source.

There is also a carbon saving in clearing out residue such as forestry leavings and sawmill shavings which could otherwise release more emissions intensive methane gas.

But recapturing the carbon from wood pellets takes decades, and the off-setting can only work if the pellets are made with wood from sustainable sources.

As a next stage, CCC is in favour of plans to make biomass carbon negative by capturing and burying the emissions under the North Sea in depleted oil and gas fields – which could cost up to £3bn in subsidies.

Labour has even lent the proposal it’s backing, with Rachel Reeves prepared to invest alongside Drax in carbon capture technology if it wins the next election.

Instead, it would be more transparent for pledged subsidies paid out under renewable obligation deals and contracts for difference to be tapered off by DESNZ by the end of the decade.

With such a vast pipeline of wind and solar power, and the possibility of reviving nuclear, Drax is a headache that frankly the government could live without.

Tackling planning laws, development logjams and supply chain challenges that are impeding on the UK’s greener future is a far more fruitful use of the government’s time and taxpayer money than propping up an energy source that belongs in the past.