It’s a myth that ETFs are eating the world

‘Software is eating the world’: so wrote the US venture capitalist Marc Andreessen back in 2011. From today’s perspective, with companies like Alphabet, Microsoft and Meta dominating the stock markets, Andreessen’s observation seems to have held up.

Had BlackRock chief executive Larry Fink made similar comments about exchange-traded funds (ETFs) 11 years ago, he likewise would look prescient today.

But despite its phenomenal growth over the past decade, not all is well in ETF land.

ETF sceptics are growing louder, their criticisms more pointed. Active managers — who are totally unbiased, by the way — believe passive investing is distorting the stock market. The efficiency of capital markets may have increased amid greater integration of the global economy, they say, but ETFs are skewing the pricing efficiency of single securities.

With these critiques in mind, what effect has passive investing, including ETFs and mutual funds that track indices, had on the US stock market?

ETFs’ popularity surge

ETFs are the most successful financial innovation of the last generation. As of 31 October 2021, more than 8,000 ETFs manage close to $10 trillion in global assets, according to ETFGI research.

ETFs are not just core investment products for retail and professional investors but also for central banks. For example, the Bank of Japan has acquired majority ownership of Japanese ETFs through its quantitative easing (QE) programme, which would have been unimaginable a few years ago.

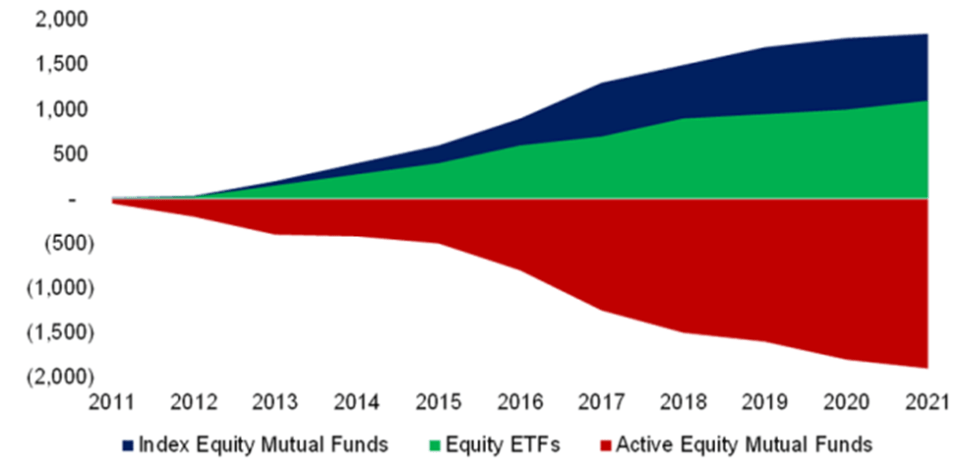

Of course, there is no free lunch in the markets. The ETF industry’s success has come at the expense of actively managed mutual funds. Active funds have consistently lost market share to ETFs and indexed mutual funds. The trend is unlikely to slow or reverse anytime soon.

The only question is what the ultimate ratio between active and passive will be. Conventional estimates anticipate passive products will capture at least two-thirds of the market.

The rise of ETFs: US equity flows, in US billions

Passive products own just fraction of stock market

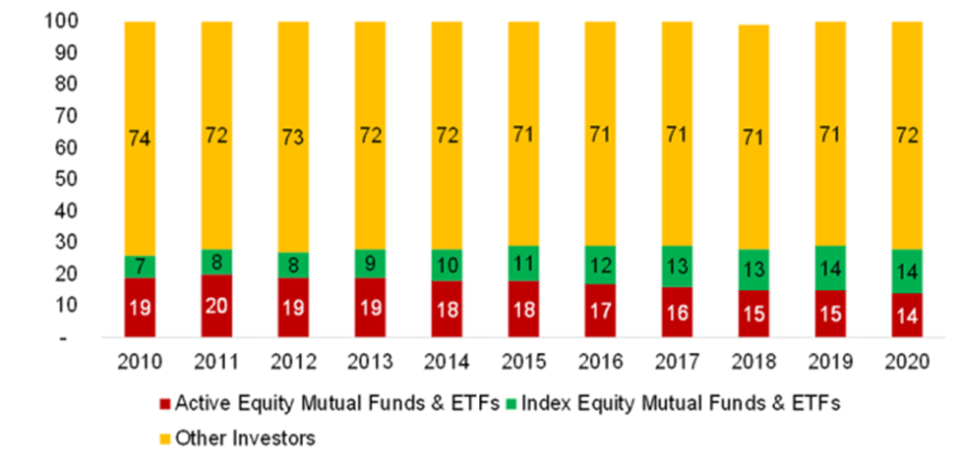

But fear-mongering aside, passive products are not taking over the whole investment world. They own only a fraction of the total US stock market. Combined active and passive funds own only 28 per cent of US stocks as of 2020, up from 26 per cent in 2010.

Pension funds, hedge funds, insurance companies, family offices and retail investors are still the majority owners of US stocks. Their combined market share — 72 per cent — has barely budged over the past decade.

Fund management companies such as BlackRock and Vanguard, which manage $10 trillion and $7.2 trillion, respectively, are not as all-powerful an influence as popular perception would have us believe.

Passive is not massive: percentage of US stock market capitalization

ETF activity mostly in secondary market

Most passive products track indices and so tend to ignore corporate news. Active fund managers, on the other hand, respond and react to these events, updating their valuation models accordingly. This results in buying and selling decisions. If passive funds simply track their index in the face of fundamental changes, ETF sceptics contend, aren’t they making fundamentals less relevant and the markets less efficient?

That might be true if there were only a few ETFs. But there are thousands and they replicate the behaviour of active managers. For example, if an S&P 500 company increases its dividend, it won’t matter much for the ETFs tracking the index. But it will matter for dividend yield-focused strategies and will likely increase the demand for them. The reaction may only occur when the index is rebalanced, but the point is clear. Fundamentals matter for passive products. As for active ETFs, which have grown popular, they pay as much attention to the news as active mutual funds.

Critics also maintain that ETFs have begun to dominate trading in US stocks. But it’s important to differentiate between primary and secondary trading. Most ETF activity occurs in the secondary market: the ETF simply changes hands, moving from one shareholder to the next, without affecting the underlying stocks.

As a share of total US stock trading, ETF secondary trading has remained almost constant at 25 per cent since 2011. This despite thousands of new products and trillions more in assets under management (AUM).

What about the primary market activity that occurs when ETF shares are created or redeemed by the associated participants? In this case, the underlying stocks are bought or sold, so there is a direct market impact.

Again, since 2011, as a share of total US stock trading, ETF primary market activity has barely budged. ETFs account for an insignificant five per cent of this trading.

ETFs’ impact via factor investing

Beyond analysing ETF trading statistics, how else can we measure the ETF effect on the stock market?

Stock correlation and dispersion are standard metrics, but they don’t reveal any consistent trends in the decade since ETFs started to take off. Sometimes stocks are more correlated and less dispersed, but this seems cyclical rather than structural.

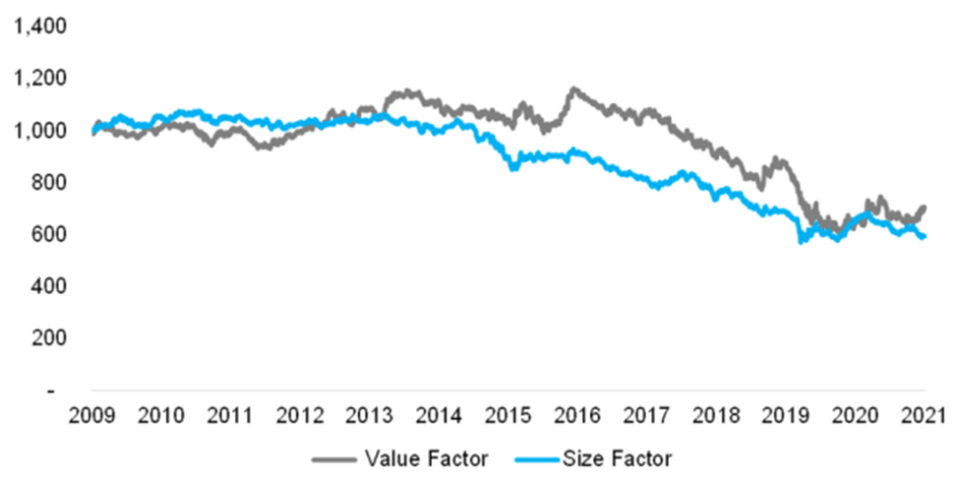

What about factor investing, which primarily reflects investor behaviour? Does that yield any insight? As passive products capture greater market share, index membership becomes more important. Stocks outside major indices such as the S&P 500 draw less interest, which should lead to decreasing valuations and market capitalisations. Positive and negative feedback loops should become stronger.

And indeed, if we look at the value factor in the US, expensive stocks outperformed cheap ones consistently since 2009. The size factor did just as poorly, as large caps outperformed small caps.

While it’s easy to blame the supposed demise of the value and size factors on the rise of passive investing, that would be premature. After all, between 1982 and 2000, an era of little or no passive investing, the size factor generated negative returns. Value investing also experienced decades of poor performance over the past century.

US value and size factor performance, Beta-Neutral, Long–Short

ETFs’ proliferation dilutes original purpose

Although ETFs are great tools for investors, their original underlying purpose has been corrupted.

‘Active management has failed. Just buy the index through an ETF’: that was the initial pitch for the ETF. And it worked — for a handful of ETFs that track the S&P 500 and other major indices.

But Wall Street is a sales machine and accordingly launched thousands of ETF products. Investors were lured away from the ETF’s first and most valuable use case. After all, the optimal portfolio for most investors is a bland one composed of a couple of stock and bond indices.

Today, there are more than 2,000 equity-focused ETFs in the US and only about 3,000 US stocks. These ETFs cover every imaginable strategy and are almost all active bets.

This is definitely not what the ETF’s creators had intended.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

By Nicolas Rabener, managing director of FactorResearch, which provides quantitative solutions for factor investing.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / jorgelum