Is it over now? Where next for the banking crisis in Europe

Is that it? After a few weeks of exhilarating volatility, European banking stocks have settled into a more reliable pattern.

It seems dramatic regulatory interventions have stemmed the possibility of immediate financial difficulties.

The question now is whether the events of the past few weeks are symptoms of wider financial problems which will be brought to light as interest rates rise.

This was the warning issued by Larry Fink. In his annual letter Fink warned that we may see a “slow rolling crisis” as the steadily increasing cost of borrowing makes its way through the global financial system.

JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon agreed that we’re not out of the woods just yet. He said the crisis is “not yet over”.

So what are the most important pressure points that European banks are most likely to face over the next few weeks and months?

Funding costs

Banks were already going to face higher funding costs over the short term as they are likely to have to pay higher interest rates on deposits.

Although higher interest rates have widened lenders’ net interest margin – the difference between what banks pay out and receive in interest – many European banks are facing both regulatory and market pressure to give more money back to customers.

Higher rates incentivises investors to search for higher-yielding products outside banks.

Analysts at Barclays have forecast that $1.5trn (£1.2trn) will be invested in low risk money market funds over the next year. According to data from the Investment Company Institute, assets at money market funds jumped by $304bn in the three weeks to 29 March.

This will encourage banks to offer higher rates to maintain their deposit base.

Banks are also facing regulatory pressure to increase interest rates. In the UK, MPs have repeatedly queried why banks have not passed on higher interest rates to savers while demanding more money from mortgages.

On top of this, recent banking volatility and the wipeout of Credit Suisse’s AT1 bondholders in particular has put even more pressure on European banks.

An AT1 bond is converted into equity if a bank falls below a certain, pre-decided strength or capital limit. They’re a creation of post-financial crisis reforms and help a bank to meet capital requirements.

Since the Credit Suisse deal, however, investors have demanded a ‘risk premium’ to hold an asset that some fear could be completely wiped out when push comes to shove.

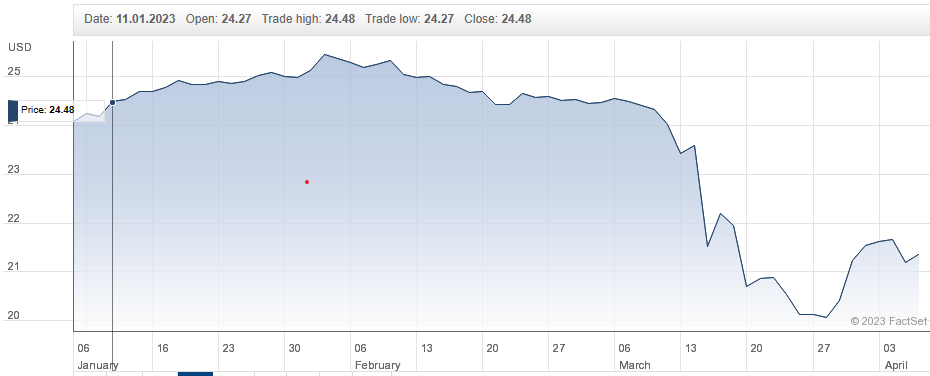

While the Invesco index of AT1 bonds has nearly recovered to its level immediately before the Credit Suisse takeover, it remains well off the levels seen before SVB’s collapse meaning banks are still paying more for an important source of funding.

“It remains unclear whether the higher yields are a short term issue or a new state of play,” Saxo’s head of equity Peter Garnry said.

Regulators in the UK and EU have both tried to reassure markets that they wouldn’t follow the Swiss example in promoting shareholders above bondholders.

Aviva Investors’ Sunil Krishnan said “given the regulatory assurances given in the euro area and the UK on the seniority of AT1 debt, it seems likely that these markets will slowly heal and become viable again”.

While funding costs are an issue for European banks, experts were confident unrealised losses – which proved so damaging for Silicon Valley Bank – would not pose such a risk.

“No (European) bank seems as exposed to deposit runs forcing Hold to Maturity sales as was the case at SVB or even Credit Suisse,” Krishnan said.

Commercial real estate

Another area of concern for European banks is their relationship with the commercial real estate (CRE) market.

JP Morgan estimates the value of European banks’ exposure to real estate at around €1.6-1.9trn, or 8 per cent of European banks’ total loan book. CRE makes up twenty per cent of total corporate loans in Europe.

CRE has been an area of concern in Europe for the last few years with the pandemic and the rise of flexible working denting office valuations.

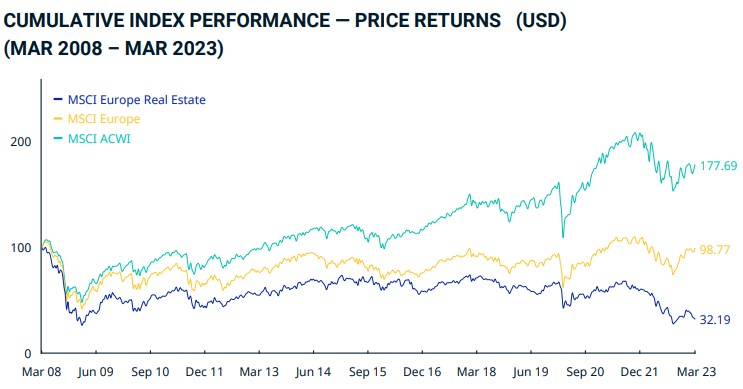

The MSCI Europe Real Estate Index, which tracks the share prices of European property companies, recently hit its lowest level since 2009.

The ECB flagged it as a “key vulnerability” for European banks last year, while in its recent Financial Stability Report the Bank of England said it was a “potentially vulnerable sector globally, as higher interest rates reduce property values along with borrowers’ ability to service debt”.

As Garnry notes, “dynamics around real estate assets are important because they are big driver of collateral values on banks’ balance sheets and thus a key driver of credit extension in the economy.”

There is therefore a risk of a doomloop as falling real estate prices from tighter credit conditions depresses lending, further depressing real estate value.

Real estate is hardly a liquid asset either. If banks need to free up funds fast then they may be forced to sell real estate assets at a loss.

Garnry suggests that Sweden will provide a testing ground of what to expect in other European countries.

“Sweden will provide a testing ground of what to expect in other countries, because households apply more adjusted mortgages in the financing of real estate than any other country and thus the downside sensitivity to higher interest rates is just higher in Sweden,” he said.

Banking crisis to credit tightening

Higher funding costs and declining values in commercial real estate both point to more conservative lending strategies.

CME Group’s Erik Norland described recent events as a “harbinger of what’s to come…we may soon see much tighter credit conditions.”

Indeed, there’s already evidence that credit conditions are tightening, irrespective of the banking crisis.

The latest figures from the eurozone showed that there was a credit contraction before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. Growth of M3 money supply, a broad measure of the money supply, slowed to 2.9 per cent year-over-year in February, from 3.5 per cent in January.

Analysts at Pantheon Macroeconomics said that data from the Eurozone adds to “the picture that liquidity conditions in the banking sector tightened further at the start of the year.”

“These data do not capture any hit to either deposits or lending from the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature, and the restructuring of Credit Suisse,” they added, implying that worse is to come.

The potential coming credit crunch will put pressure on central banks to ease off their battle to tame inflation, but so far they have stayed the course. Announcing the ECB’s most recent decision, President Christine Lagarde said “there’s no trade-off between financial stability and price stability”. Further interest rate hikes will restrict credit creation further.

If credit conditions are already tightening then the events of recent weeks will only encourage that trend. While European banks are well-capitalised enough to avoid a 2008-style banking meltdown, the broader economy is unlikely to escape the impact of March’s mini-crisis entirely.