Is Brexit the real reason for London’s stock market malaise?

The City has been plunged into something of an existential panic in recent months. Fears of international decline have crystallised in the form of a listings drought and a crack squad of City grandees are scrambling to try and steady the ship.

But the causes of that decline, the levers that can be pulled, and whether indeed there is a decline at all, are complex issues.

A sharp drop-off in pension funds flowing into the stock market and a risk averse culture among the Square Mile’s money managers have been pointed to as reasons for the fall in the UK’s standing, as has restrictive regulation and burdensome reporting requirements.

There is also the valid point that the UK’s listings slump, while sharper than most countries, is part of a much wider global trend in which the IPO market has been shuttered amid the tumult of war in Ukraine and soaring inflation.

But one possible explanation divides opinion among City watchers more than others: Brexit.

Discount store

The battle to win listings in London is often a fight against a brutal and simple logic: a New York listing is likely to fetch a higher valuation – so why wouldn’t you?

The attention of policymakers is therefore trained on the underlying cause of the UK’s valuation discount and why firms on our shores have proved such laggards.

The reason du jour touted in the City is that the lack of pension fund cash flowing into the stock market has fuelled the decline in valuations, which is in turn blamed on accounting tweaks brought in around the turn of the millennium.

Pension funds’ holding of equities has indeed plummeted since 2000. Just four per cent of the UK stock market is now held by pension funds – down from 39 per cent in 2000, according to a report from think tank New Financial.

However, valuations did not correlate with that decline. As Fidelity fund manager Alex Wright pointed out earlier this month, much of that de-equitisation was done by 2015, and the valuation of the UK market “held up roughly the same”.

He says the elephant in the room came after that – in June 2016.

“Unfortunately, and again politicians don’t want to say this, but it’s very clear what’s caused the undervaluation: it’s Brexit,” he told Citywire in an interview.

“You can see it to the day that international investors have disinvested from the UK market after the Brexit vote and the uncertainty that that has created. That is the key reason.”

Analysts at Capital Economics similarly point out the emergence of a gap in equity valuations doesn’t tally with the timing of the pension accounting changes and it was only from 2016 that a substantial gap emerged.

Smoking gun?

Given the timing, it’s tempting to attribute that gap solely to the UK’s vote to leave the EU, analyst Adam Hoyes of Capital Economics tells City A.M.

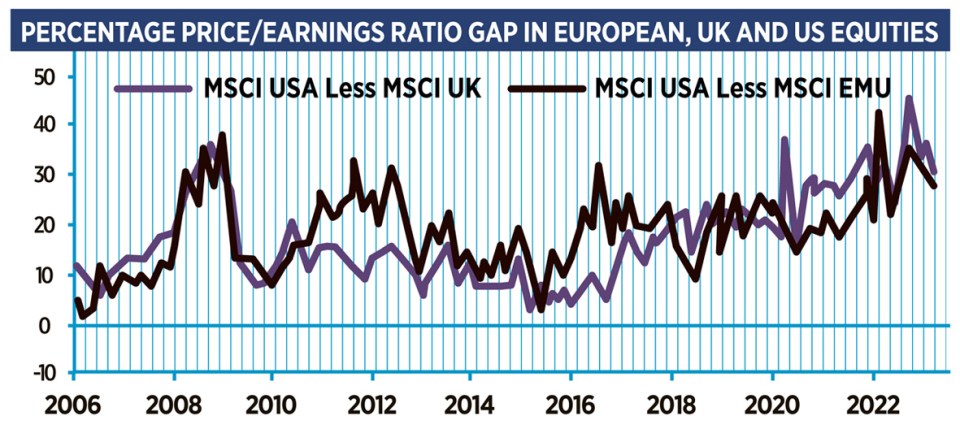

The price/earnings ratio of UK firms, which compares a company’s share price to its annual net profits, was broadly comparable to the US up until 2016. It was only at that point that they began to diverge.

“It looks like a bit of a smoking gun” Hoyes tells City A.M.. But, he cautions, the reason may in fact be more muddy.

“You also got a real divergence in valuations between the US and the Eurozone around that time,” he adds. “That is the real pushback I give against it being solely a Brexit effect.”

The EU similarly began to deviate from the US in terms of valuation just prior to Brexit. Much of the valuation discount may in fact, he says, be a simple assessment of the UK and EU’s long term economic prospects against the US in that time.

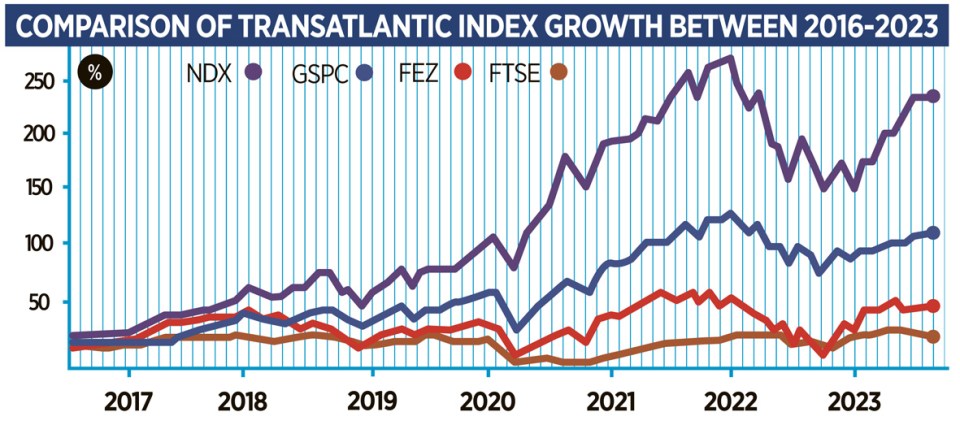

Investors’ cash is not restricted by borders, and money managers may have just chosen to follow the more rosy economic outlook on the other side of the Atlantic.

Global IPO Market

It is also important to note the global picture of a major listings slowdown. The IPO market globally has been largely shuttered for the past year and the UK is not alone in that regard.

Global IPO activity was down by eight per cent in terms of deal numbers and 61 per cent in terms of proceeds compared to the same period last year, according to data from EY.

The amount of cash raised via UK IPOs did fall more sharply, however, with cash raised falling some 80 per cent on the same period in 2022, and 99 per cent on the blockbuster 2021 levels.

But for William Wright, the director of think tank New Financial, even taking into account that UK slump, the wider global picture shows that it is not Brexit that has dampened the UK’s appeal.

“I wouldn’t personally put Brexit towards the top of the list or even on on the list,” he tells City A.M.

“If Brexit were a significant factor in the recent slowdown in IPOs in the UK, then surely the markets in the rest of the European Union, which were very active in 2021, would have continued to be very active in 2022 and into 2023 – and they just haven’t been.

“This is not a UK specific problem,” he adds.

The fact the UK’s IPO market was going gangbusters in 2021 may also point to that argument. Britain had left the EU by then and it did not then prove to be too much of a deterrent for scores of firms to debut in London.

For Wright, the reason for the current slump is the more macro assessment of the current state UK economy.

“The only way that Brexit could be a factor is the extent – and one can argue this till the cows come home – to which Brexit has had a drag effect on the UK economy,” he said.

Drag effect

It’s there that Brexit may loom more definitively into view. As both Wright and Capital Economic point out, the reason for the decline may be firms voting with their feet on Britain’s economic prospects.

The UK economy is estimated to be 5.5 per cent poorer now than it would have been had it stayed in the EU, according to a study by the Centre for European Reform.

Britain has also lost out on business investment worth £29bn since the referendum, according to a study by a senior Bank of England rate-setter earlier this year.

Imports and exports of goods have also felt a “significant adverse impact” as a result of Brexit, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility.

While Brexit may not be solely responsible for dragging down London’s capital markets, its looming spectre over the UK economy may have caused them to lose their shine.