This investment clock says what assets to buy and when

By Tom Bailey from interactive investor.

It’s inevitable that the unremitting global economic cycle will impact stock markets, but when?

The economist Paul Samuelson once joked that the stock market has predicted nine of the past seven recessions. But while the over-reactive nature of equity market investors and their poor predictive powers ring true, there is nonetheless a clear link between economic and market performance, at least in advanced economies.

Indeed, between the 1929 crash and the global financial crisis of 2008, there were 10 bear markets – periods when global equity markets declined by more than 20% from peak to trough. Only two – the flash crash of 1962 and 1987’s Black Monday crash – were not accompanied by a recession.

This correlation makes sense. During a recession, consumers spend less, businesses invest less, loans are defaulted on, vendors go unpaid and companies go bust. This wreaks havoc on the profitability of firms and sometimes threatens their survival, causing their share prices to slide.

Weak global economic growth, then, is a major concern for investors. But how worried should they be? To gauge the health of the global economy, it is worth looking at the health of the world’s two largest economies, the US and China. With global economies and supply chains more connected than ever, what happens in these economies will have profound implications for the rest of the world.

Never-ending cycle

The US economy cycles constantly. At the bottom, consumers stop spending, and firms cut investment and recruitment. Banks limit lending, restricting consumption and investment. Pessimism rules. This was the story with the US economy after the 2008 financial crisis, as it slipped into recession.

At some point, pessimism starts to dissipate; hiring, spending, lending and investment resume, and growth picks up as the economy expands. Optimism takes hold and the economy grows. This is where the US currently is in its cycle.

However, these trends will peak and eventually go into reverse: the economy will enter a recession and return to the bottom of the cycle. The current expansion in the US economy is the longest on record, so fears are mounting that the cycle may be turning.

Economists and investors pore over mountains of data and indicators – from car production figures to birth rates – to try to work out where the US is in its cycle. Thomas Becket, chief investment officer at Psigma Investment Management, notes that some indicators have shown weakness lately. He points out that US haulage industry growth and US existing home sales appear to be falling, suggesting a slowdown in economic activity.

There is an obvious pattern from “strong to not so strong”, he says.

“This is because the Trump-inspired fiscal impulse is starting to wane or the US has been infected by slumping growth rates from other parts of the world, or both factors.”

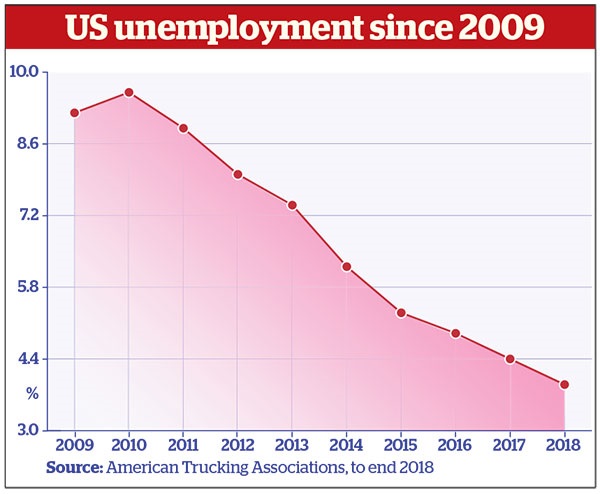

That said, these indicators are always prone to fluctuations and to sending misleading signals. The best indicators for gauging economic strength, according to Peter Elston, chief investment officer at Seneca Investment Managers, are the unemployment rate and the yield curve.

Two telltale signs

First, unemployment. In a recession, the labour supply is greater than demand. As the economy kicks into recovery mode, demand for workers increases and supply decreases, pushing up wages. This is where the US economy currently is. Recent data suggests that wages are starting to pick up.

This is good news for workers. However, wage growth could drive up inflation that the US Federal Reserve would then manage by raising interest rates, which could choke off economic growth.

Such a scenario doesn’t currently look likely, though, as inflationary pressure from wage growth remains minimal. Alex Neilson, investment manager at Investec Wealth Investment, says:

“We expect a pick-up in wage growth, but we just aren’t seeing it currently.”

Eventually, however, wage growth will surge and the Federal Reserve is then likely to step in. Strengthening wage growth in 2018 suggests this point is approaching. Nominal wages were up 4.2 per cent in November 2018 compared with the same month in 2017.

Elston says the yield curve is a better indicator than the unemployment rate.

He adds: “Much research shows that it is by far the best recession indicator if you are looking 12-18 months ahead.

Ed Smith, head of asset allocation research at Rathbones, explains:

“The term ‘yield curve’ is used as shorthand for the difference between the yields on 10-year and two-year US Treasury bonds. A negative reading is called an inversion, and is unusual. It signals that the economy may be overheating in the short run and can trigger rate rises that choke off growth.”

Elston says the yield curve in the US is currently flat. He adds: “That tells me recession is not imminent.” This underlines his belief that the US economy is peaking in its cycle but is some way from recession.

How to generate a £10,000 income: 2019’s investment trust picks

China’s transition

It’s widely argued that China’s past decade of economic growth has been the principal driver of the global economy. Jeremy Lang, portfolio manager at Ardevora, says:

“We believe China has directly contributed almost 50 per cent of global economic growth since 2009, and emerging markets have contributed a further 25 per cent.”

However, with the Chinese economy’s growth rate recently falling to its lowest level in three decades (6.6 per cent), fear is growing that China’s economy is now on a trajectory of lower economic growth. “If the world cannot benefit from growth in China, growth becomes very hard,” says Lang.

At heart of the problem is the country’s reaction to the 2008 financial crisis. The Chinese authorities responded to the global slump by unleashing a wave of credit and fiscal expansion in 2016. This helped support the Chinese economy and thus (as Lang notes) the global economy. But it has created two problems for the Chinese economy.

First, it has resulted in a huge build-up of corporate, consumer and local municipality debt, fuelling fears over bad debts and defaults. Secondly, China’s stimulus may now be harming its economy. George Magnus in his book Red Flags: Why Xi’s China is in Jeopardy argues that the post-2008 stimulus has largely been spent on infrastructure, property construction and the financing of state-owned enterprises. Banks, told to lend by the state, did not generally identify and finance highly productive or innovative firms. The result has been that the Chinese economy is becoming less efficient.

China, aware of these problems, has attempted to address them by reining in credit. But this has led to a slowdown in the Chinese economy that has been felt around the world. Export-oriented manufacturing in Germany, for example, has flagged. This has had a knock-on effect on other countries integrated into German manufacturers’ supply chains such as Italy, which slipped into recession in the second half of 2018. The global economy – having become dependent on Chinese growth in the post-financial crisis years – is likely to take a hit should growth in China fall back further.

That said, many investors are betting on a new wave of stimulus in China. Becket says: “Thus far in 2019 the market has been buoyed by the fact that China is stimulating its economy through both fiscal and monetary measures.” However, he adds: “China has been far less aggressive [with its stimulus] than it was in 2016. Of course, this might change. The Chinese could “push the pedal to the metal’ later in the year if there is no tangible improvement, but as yet their efforts are not having a major impact.”

Position for an inevitable economic downturn

Positioning for a recession is not easy. Many experts advise against it, arguing that it is impossible to know when exactly markets will start pricing in an anticipated turn in the economic cycle and that investors risk acting too late or missing out on what’s left of the growth phase.

Not everyone agrees, though. Elston is reducing his overweight position in equities in anticipation of a recession. But he says it’s important to make gradual adjustments, as you won’t be able to time your move to coincide exactly with market falls.

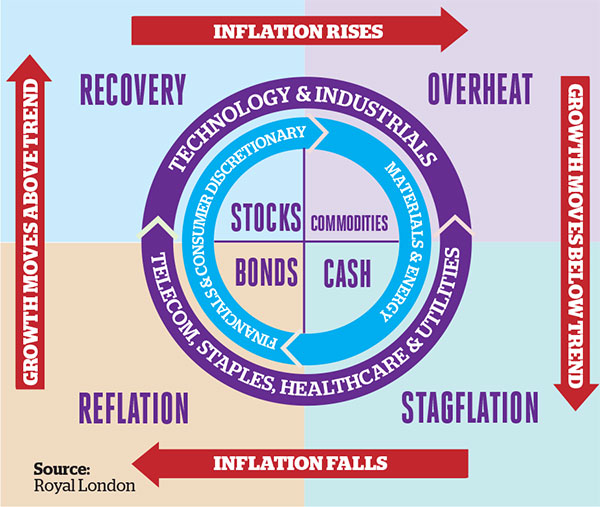

Trevor Greetham, head of multi-asset at Royal London, has developed an ‘investment clock’ (pictured below) that indicates which asset classes investors should consider at different points in the business cycle.

According to Greetham, we are in a reflationary period: “The phase of the business cycle in which central banks tend to cut, not raise, interest rates”.

Fears over economic growth, business confidence and market volatility have pushed central banks into relaxing their monetary policies. Greetham argues that investors should now be looking to invest in government bonds, financials and consumer discretionary stocks.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser