Inside the psychedelics renaissance making waves in mental health care

Harley Street has historically been the home of doctors and dentists in London. Today, it hosts an extensive range of health specialists, accessible at usually prohibitive costs. But walking inside the Clerkenwell Health clinic, just around the corner, feels different. The rooms have high ceilings and the walls are painted in a palette of tamed, light colours. The soft light comes from mushroom-shaped chandeliers. The attention to detail is palpable. And for the right reasons: it is a site for psychedelic clinical trials, where patients need to feel at ease while they are administered doses of psilocybin, one of the compounds of what we know as “magic mushrooms”.

CEO Tom McDonald and CFO Sam Lewis have ridden the recent wave of “psychedelic renaissance”. They’ve built what they call a “psychedelics contract research organisation” where they’ll help companies shape clinical trials and train therapists who will assist during the dosing sessions. They’re part of an industry in the making, and this comes with its own complexities.

Psilocybin and other psychedelic compounds have shown a positive impact on people suffering from treatment-resistant depression, addiction and PTSD. Clinical trials have been run in the UK and the US with different variations of drugs, conditions and number of patients. The first trial at Clerkenwell Health will be with patients in palliative care – people with complex and often terminal illnesses.

The carefully recruited patients are divided into two groups: one will only get a placebo, or a really low dose, while the other will get a higher dose of psilocybin. The day before dosing, they’ll come to the site for a 90-minute session with their therapist. On the next day, the session usually lasts between six and eight hours. The patient lies in bed with an eye mask on, listening to specifically designed music, with therapists at their side to offer guidance. The day after they’ll speak with the therapist to unpack the experience and understand its meaning. Then they’ll have follow-up sessions to follow the progress – or lack thereof. This treatment can sometimes have a short-lived positive impact.

Participants of psychedelics clinical trials have described a sense of reconnection to life and reclaiming of presence, and enhanced emotional responsiveness. Psilocybin hits the brain, reducing connections with some of its areas that are closely linked to depression. It resets the activity of specific brain circuits.

The results coming out of different studies have been promising: Compass Pathways, the leading British company in this space, is now preparing phase 3 of its psilocybin trial. According to Dr Guy Goodwin, chief medical officer at Compass, success will simply look like a “repetition of phase 2”. The latter was conducted in 22 locations, in 10 countries. If phase 3 produces positive results, that would mean marketing authorisation in the US. It could be groundbreaking.

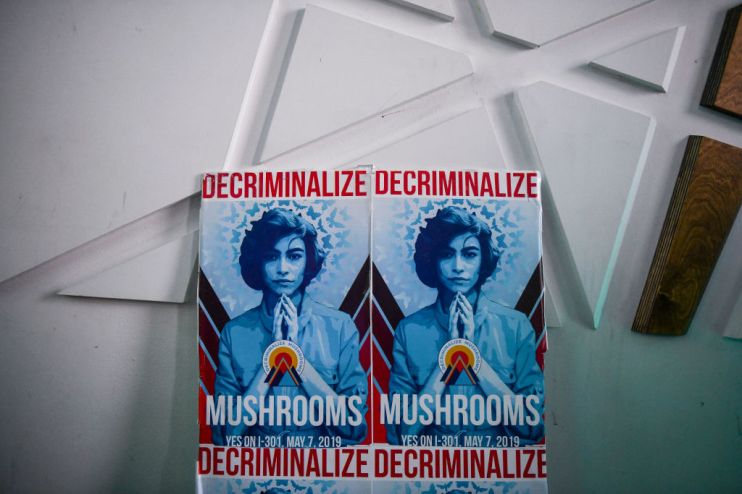

Oregon and Colorado have voted to legalise psilocybin therapy. In Canada, patients with life-threatening mental health issues can be treated with psilocybin and MDMA. In the UK, psychedelics are still Class A, Schedule 1, meaning they’re considered not to have therapeutic value. “It’s an absurdity and it flies in the face of science”, says Amanda Feilding, the founder of the Beckley Foundation. Over decades of lobbying, she was faced with resistance, and sometimes even scorn. Now, the tide might be turning.

“There’s quite a favourable momentum here with the regulators”, says McDonald when asked why he picked the UK for his business. What’s more, fifty-five per cent of the public support relaxing restrictions on psilocybin to make research easier, and 58 per cent support changes to the law to permit terminally ill patients to access psilocybin-assisted therapy.

It’s important to remember that behind the stained glass there is a world of struggle and pain. Those who have tried this treatment so far have serious mental health problems or life-threatening illnesses. They join the trials with the full knowledge that the process might not work for them, and that they could be back at square one. The pressure is immense, and it takes a lot of courage. No matter what pharma companies and drug developers say on their websites, psychedelic therapy won’t be a silver bullet for everyone. Scientific results must be separated from the often unhelpful hype. But, if it works for even one person, then it’s a path very much worth taking.