Inside Africa’s megacity: God, oil, and traffic chaos in Lagos

From the Nollywood film industry to shanty-dwellers with a line in tech imports, Nigeria’s biggest city reveals its secrets to Alex Dymoke

NO ONE knows quite how many people live in Lagos. Nigeria’s 2006 census put the official figure at just under 8m. The UN estimated the number for 2011 at 11.2m. Others say it’s now somewhere nearer to 21m – a fittingly large margin of error for a city so chaotic.

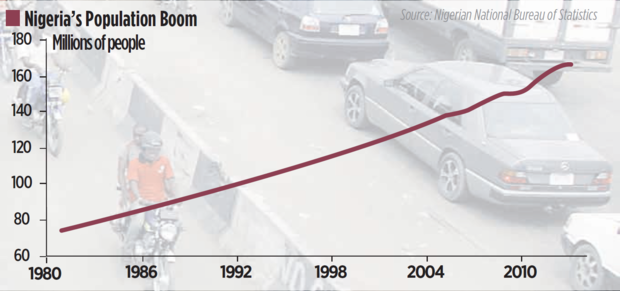

Whatever the exact figure, one thing is certain: it’s growing. Nigeria is Africa’s most populous nation, and Lagos – the commercial capital – is the country’s biggest city. Economic growth will bring the arrival of yet more people. Lagos’s governor is planning for a city of 40m. At its current rate of growth, Nigeria will have a population of 300m in 25 years.

The change is happening at such a rate that Nigeria’s image in the eyes of the world hasn’t kept up. Since gaining independence in 1960, a steady line of military dictatorships and a devastating civil war left it with a reputation for corruption, kidnappings and the longest traffic jams on earth. A few days before I arrived, I bought the only up-to-date visitors’ guide to Nigeria on sale in the UK. “This brave guidebook does not seek to oversell its destination”, said the press quote on the back – not exactly a ringing endorsement.

ACHIEVING THE UNTHINKABLE

But things have changed. Nigeria has been a democracy since 1999 and, in Lagos State at least, recent years have seen the first tangible improvements in living memory. In 2007 and 2011, Lagos elected and re-elected Babatunde Fashola, a pragmatic lawyer who managed to jump-start the mechanisms of government and achieved the unthinkable by achieving something. Underpasses have been cleared, a bus system was launched in 2008, and petty crime has fallen.

Once a city to be avoided, luxury brands have moved in. On my first night, I’m invited to the opening of an international photography festival called LagosPhoto. It’s a swanky event held at Eko, the hotel of choice for the city’s many traveling oil company employees. In the corner, a bar serves Moet champagne cocktails. Outside the exhibition, Porsche – one of its sponsors – has parked a gleaming new Carerra.

Where there is money in Nigeria, there is lots of money. This is evidenced by the recent trend for young Nigerians to come to London. Selfridges has put up signs in the indigenous Nigerian language Yoruba. According to Global Blue, of all nationalities, Nigerians are the fourth highest-spending buyers of duty-free shopping in Britain. And Nigeria’s newspapers were recently up in arms about a proposal to introduce a £3,000 bond for Nigerian visitors wanting a UK visa. The idea has since been shelved, amid fears that Nigeria’s rich would depart for Paris.

But at the LagosPhoto opening, it doesn’t take long for the illusion to be shattered. Two hours in, there’s a power cut and the lights go off. Suddenly, all the beautifully dressed people are standing in the dark. This is the Nigerian brand of prosperity: designer clothes, sports cars, but no 24-hour electricity or clean water supply.

WEALTH WITHOUT FREEDOM

If the mansions of Ikoyi and Victoria Island tell one side of the story, the security guards and barbed wire that surround them tell the other. Wealth doesn’t entail freedom like in the West. The rich buy a plot of serenity away from the hubbub, and build high walls around it. The private security industry thrives. Guards dressed in mock-military uniform keep watch outside houses, cash points, shopping centres and fast food restaurants. I ask a Nigerian friend why there is an armed security guard outside Tastee Chicken, the Nigerian equivalent of KFC. “Fast food is expensive here; it’s for rich people. Where there’s rich people, there’s security.”

But money offers scant protection from the most trying aspect of Lagos life: traffic. Aggression is imperative; timidity on the road is seized upon, cut up, over-taken, honked at. All drivers seem to all be afflicted with honk-tourettes. Once I got in a taxi late at night when there wasn’t a single other car on the road, and the driver still tooted his horn at five second intervals for the entire journey. Things are better than they were, but Lagos still gridlocks twice daily, as millions hit the bottleneck that leads from the mainland to the commercial districts on the Islands. I heard one story of a man who dropped his British niece at Lagos airport to catch a flight to London. When he received her text saying that she had landed safely at Heathrow, he was still in traffic on the way back from the airport.

When I was there, the only speedy way to get around was to take one of the city’s 40,000 or so Okadas – little 100cc bikes that zip and buzz in and out of the traffic like mosquitoes. Lagosians have a love-hate relationship with Okadas, and their use has since been restricted. They drive with a kamikaze disregard for passengers and pedestrians, and make good business flouting the rules of the road. But Okadas are a necessity. It is not uncommon to see smartly dressed businessmen skip out of a traffic-jammed Mercedes, hail an Okada, and zip off to an important meeting.

The problem of overburdened roads is exacerbated by constant fuel shortages. When fuel is scarce, cars queue for hours outside petrol stations, or creep along main roads, bartering with hawkers selling petrol out of plastic cartons. “There has been a fuel scarcity for three weeks now,” one driver tells me. He refuses to switch on the air conditioning, despite the humidity. “I am trying not to waste fuel because I am not sure when I can get it again.”

THE RESOURCE CURSE

The bright predictions for Nigeria’s future will only be realised if there are major improvements in the power supply. Only 40m Nigerians currently have reliable access to electricity, the country’s power minister said recently. With a population of 168m, more than 120m live in the dark. And if any business wants to function reliably, they have no choice but to invest in a fuel-guzzling generator. The all-pervasive smell of petrol wafting from these generators serves as a constant reminder of the Nigerian blessing that many say has turned into a curse: oil.

That the largest oil producer in Africa, and the eleventh largest in the world, is unable to provide a steady supply of fuel to its own people is a perpetual source of frustration for Nigerians. Despite the Niger Delta’s plentiful reserves, there are only four poorly-functioning state-owned oil refineries in Nigeria. Earlier this month, the petroleum minister announced plans to begin privatising them after an audit criticised inadequate government funding and “sub-optimal performance”. Despite being Africa’s top crude exporter, Nigeria relies on fuel imports to meet more than 70 per cent of its needs. Corrupt officials with links to past dictatorships have made huge sums exporting and importing oil, and criminals reportedly steal 100,000 barrels of oil a day. “Oil is the fastest way to make money if you are in power,” my taxi driver tells me. Is he angry? “Yes I am angry, but to be honest with you, I would do the same.”

Oil accounts for 95 per cent of Nigeria’s export earnings and 85 per cent of total government revenue. Its discovery should have improved the lives of Nigerians, but the proportion of the population living in poverty has increased over the past 20 years. Over-dependence on crude oil has resulted in the neglect of Nigeria’s agricultural and manufacturing industries, leading to severe unemployment and poverty in rural areas. This is part of the reason why so many people continue to flock to Lagos. In 1957, the year that Shell-BP struck oil in the Niger Delta region, the population of Lagos was around 450,000 – it’s now at least 40 times that number.

THE COMPUTER VILLAGE

In the absence of welfare provision, Nigerians channel a great deal of energy and ingenuity into fending for themselves. Despite breakneck economic growth and an expanding upper-middle class, 70 per cent of the population still live on under $2 a day.

In Lagos, the majority of the city’s poor earn a living flogging their wares from market stalls or as hawkers selling food on the sides of roads. The city often feels like one massive marketplace, as the streets hum with enterprise. Sit in a traffic jam on the Third Mainland Bridge for 30 minutes and you’ll be accosted by dozens of hawkers. In just one journey from the Island to the mainland I was offered: socks, nuts, cotton-wool buds, magazines, a doormat, plantain chips, picture frames, towels, Monopoly, belts, a phone charger, sausage rolls, a digital camera, spring water, a CD rack, a box of glass tumblers, a bag of disposable razors, ring-binders, watches and oven gloves. An old Lagosian joke says that, if you went to work completely naked one morning, you could arrive at your desk equipped and fully-clothed with items bought from street traders.

One of the most striking examples of Lagosian street-trading is the so-called “computer village”. This is a vast slum town, where shanties selling computers and electrical equipment cluster, some with cardboard paneling attempting to replicate the logos of big tech brands. It looks like the future as envisaged by the twentieth century’s pessimists. Think Blade Runner: screens, wires and dirt. Men sit at their stalls peering down into the circuit boards of decade-old electronic equipment, fixing for resale.

The filth and chaos suggest poverty, but when I ask traders where they get most of their stock, many say they have just flown to China or Dubai to find cheap materials to import. It is difficult to tell how much money people are making. The marketplace atmosphere results in a fast and loose attitude to cash. They make it, they spend it – it changes hands quickly.

DIVINE INTERVENTION

In evangelical Christianity, Lagos has found a brand of religion to match the energy of its streets. The preachers that bellow pieties onto cramped minibuses and the songs that emanate from churches conjure a God that is close by. He is here, advantaging you, disadvantaging your enemies, answering prayers, and making things happen in a city where nothing works. It’s no surprise that the relative solemnity of Anglicanism and Catholicism has been drowned out by the noise of Lagos living.

Evangelical Christianity also codifies a widespread belief in the power of the mind to overcome challenging circumstances. Self-help books are ubiquitous. On one market stall I came across Change your Thinking Change your Life, Hemotions – Even strong men struggle, Become a Billionaire, and Better Than Good: creating a life you can’t wait to live.

“If you want something enough, it will happen,” many Lagosians tell me. One man even describes his wife to me, gushing about her sophistication and beauty. She even had a name: Maria. Does she live with you? “No, she is just in my imagination.” I look confused. “If you imagine something and really focus on it, then it will happen,” he assures me.

The religious problems in large parts of Nigeria that have grabbed international headlines have not yet reached Lagos. In the north, jihadist group Boko Haram has terrorised the population with a series of bomb attacks on churches, schools, and police stations. The UK government currently warns against all travel by westerners to some northern regions. The majority in northern Nigeria is Muslim and the majority of people in the south is Christian, but Lagos is a big mix. In crowded marketplaces, Muslim men kneel silently in prayer, while ecstatic singing spills out of a makeshift church a couple of stalls along. The mode is tolerance rather than integration. Flare-ups are rare, but mistrust can be found simmering beneath the surface.

NOLLYWOOD’S STARS

However crowded Lagos gets, there is always space for God. He even makes his presence felt in Nollywood, Nigeria’s thriving film industry. Nollywood movies are cheaply produced moralistic tales, often filmed on handheld cameras. There is a huge appetite for them – around 70 are released every week – and the stars of the industry enjoy a level of fame comparable to the biggest Hollywood names in the West.

I was determined to see one during my time in Lagos. Mostly they’re consumed and distributed as pirate DVDs – the only cinemas are in upmarket malls and tend to screen western films – but the Silverbird cinema was showing Nollywood’s Single and Married. Despite the poor production – dialogue was frequently drowned out by the backing music – the smattering of well off Nigerians in the cinema were immediately caught by the film’s conservative Christian message. Some lurid lines jar against the piety. “My balls are dangling with the weight of unspilled sperm!” implores an undersexed husband to his workaholic wife. Uproarious laughter breaks out. The audience cheers as the promiscuous female character gets her come-uppance and the characters approach their inevitable epiphany: extra-marital sex is bad, God, fidelity and marriage are good.

It is easy to criticise Nollywood. The films are unabashedly misogynistic and reactionary. Often set in plush houses and featuring sports cars, they tantalise the population with a lifestyle that 99.99 per cent of Nigerians will never experience. But in a nation so dominated by foreign interests, this is one industry that is distinctively, proudly Nigerian. From actors, cameramen and directors to market-traders and journalists, Nollywood is a rare thing: a homegrown mass employer.

The taxi driver who takes me back to the airport for my flight home has lived all around Nigeria and has even spent a year in the UK. The place he is happiest? “Lagos, 100 per cent”. I ask him why he likes it so much. “I like living here because life here is like life in New York or in London. If you are very strong you can make money here. This is a fast city. There is so much. Anything you do here, even if you are just selling water. Look at these guys – ” he gestures to some hawkers standing in the middle the Third Mainland Bridge. “Some of them are just selling water and they are paying rent. They are making money. Whatever you sell here you will make it. there is nothing here that you couldn’t sell. There is money here. That is why I like Lagos – there is money here.”