Inflation erodes UK real pay rapidly despite record wage increases as 137,000 Brits return to workforce

UK take home pay is falling at one of the fastest paces since records began over two decades ago despite wage growth racing ahead at the quickest rate outside the pandemic, official figures out today reveal.

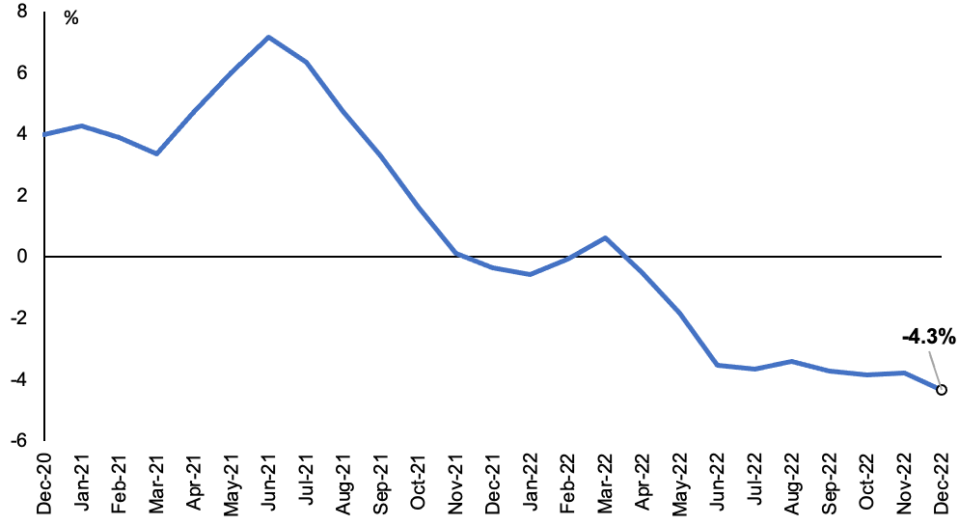

Real pay fell 4.3 per cent over the three months to December last year when using the consumer price index, Britain’s official measure of inflation, according to figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Inflation, running at double digits at the back end of last year, wiped out 6.7 per cent pay growth, which the ONS said was “the strongest growth rate seen outside of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic period”

Growth was also above market expectations and the Bank of England’s.

Household living standards fall when the rate of price growth outstrips the rate of wage growth.

Inflation last year surged to a 41-year high peak of 11.1 per cent in October, but has since fallen for two months in a row to 10.5 per cent and is expected to decline rapidly this year.

However, wages are forecast to continue to lag behind, leading economists at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, Office for Budget Responsibility and Resolution Foundation to warn of the biggest erosion to real pay on record over the next two years.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said: “The best thing we can do to make people’s wages go further is stick to our plan to halve inflation this year.”

Figures out tomorrow from the ONS are expected to show the cost of living stayed in the double-digits last month.

Private sector pay increases jumped to 7.3 per cent, while public sector wage increases climbed to 4.3 per cent, narrowing the gap between the two. The wedge is still historically high.

Real pay growth has been negative for several months in a row

“Although there is still a large gap between earnings growth in the public and private sectors, this narrowed slightly in the latest period. Overall, pay, though, continues to be outstripped by rising prices,” Darren Morgan, director of economic statistics at the ONS, said.

Britain’s unemployment was 3.7 per cent in the three months to December, a multi-decade low. But the jobless rate hit 4.1 per cent in December alone, indicating companies are responding to a weakening economy by laying off staff.

Some 137,000 people across the whole population re-entered the workforce, pushing down the economic inactivity rate, a measure of people who are unemployed and not looking for a job. The inflow was a shallower 113,000 among those aged 16-64.

Britain is forecast by the Bank to suffer a 15-month long recession that will knock around one per cent off of GDP. The country narrowly avoided a recession last year.

Increasing private sector pay raises problems for rate setters at the Bank of England, who are worried businesses will continue to hike prices to offset rising wage costs. Spending is also likely to stay strong due to household incomes rising.

“UK wage growth has come in higher than expected in the latest jobs report, and this will be a concern for the Bank of England’s hawks,” James Smith, developed markets economist at Dutch bank ING, said.

The ONS’s “release suggests that the tight labour market will remain a stubborn source of domestic inflationary pressure for some months yet,” Ashley Webb, UK economist at consultancy Capital Economics, said.

The rate of wage growth is unlikely to be compatible with the Bank achieving its two per cent inflation, raising the risk of the MPC bumping borrowing at least 25 basis points higher at the next meeting on 23 March.

“With the BoE putting greater emphasis on the lagged impact of past tightening, and with inflation likely to show signs of improvement by spring, we suspect a March rate hike will be the last,” Smith added.

Some 843,000 working days were lost to strikes in December, the highest number since November 2011.