Inflation drops for second month in a row but experts warn rate has yet to pass its peak

UK inflation has fallen for the second month in a row, but soaring food prices have led some experts to warn it may not have passed its peak yet.

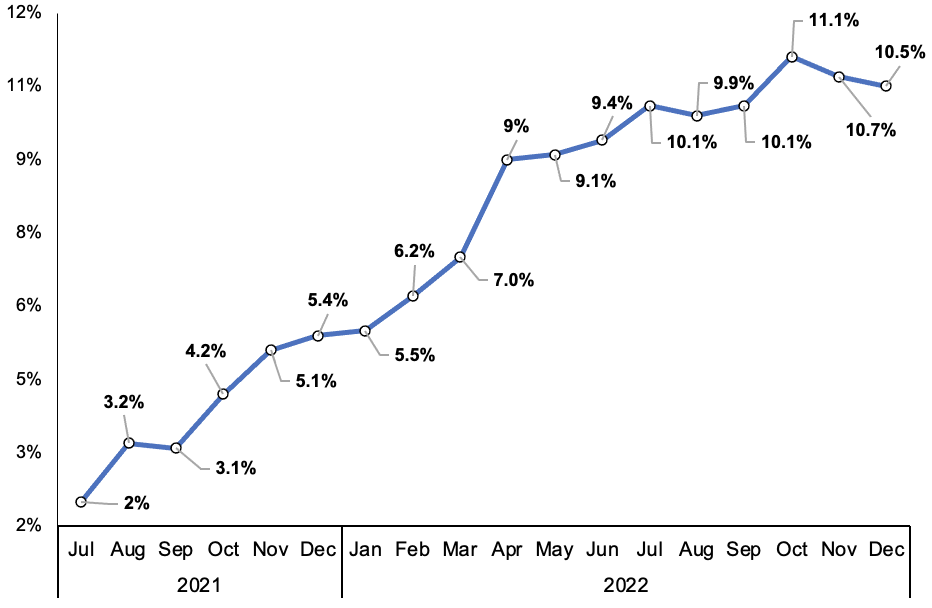

The rate of price increases dropped to 10.5 per cent in December, down from 10.7 per cent in the previous month, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said today.

The figures were in line with market expectations. It is the first time the rate has fallen in back-to-back months since the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis.

Tumbling petrol prices forced the headline rate lower, however supermarket prices are still rising at the fastest pace in recent memory.

Food inflation actually climbed to nearly 17 per cent, its hottest level since 1977, piling pressure on households who are also being squeezed by rising interest rates and elevated energy bills.

UK inflation has fallen again

Despite the top line inflation rate falling, there were signs in the ONS’s data that underlying price pressures are strong and may stick around for some time.

Services inflation jumped to 6.8 per cent from 6.3 per cent, a 30-year high, indicating pubs, bars and restaurants are passing on higher wage and input costs to consumers by lifting prices.

Core inflation – seen as a more accurate measure of underlying price pressures – was unchanged at more than six per cent, leading Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at Capital Economics, to warn that “the inflation battle is not yet won”.

January’s rate could actually jump higher due to swelling energy bills, “meaning inflation may not yet have peaked,” Paula Bejarano Carbo, associate economist at one of the UK’s oldest think tanks the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, said.

The energy price cap, which will rise to £3,000 from £2,500 in April, will keep inflation lower than it would have been had the government not intervened in the market.

Numbers from the ONS yesterday revealed private sector pay is rising more than seven per cent, among the fastest increases ever.

There is concern among economists that high inflation could set into the UK economy if wage growth fails to trim, forcing companies to keep lifting prices to protect profits.

Although nominal pay is racing ahead, inflation is wiping out pay gains. Real incomes dropped 3.4 per cent in November, the eighth successive month spending power has fallen.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt described inflation as “a nightmare for family budgets”. He and prime minister Rishi Sunak earlier this month promised to halve it by the end of the year, but economist had forecast that last November.

Experts are united in their bets on the rate of price growth gradually falling in 2023, mainly due to international energy prices plummeting from their record highs hit after Russia invaded Ukraine. Gas prices are cheaper than they were before Putin launched his assault.

However, inflation is still more than five times the Bank of England’s two per cent target, raising the risk governor Andrew Bailey and co will lift interest rates for the tenth meeting in a row on 2 February.

Analysts are divided over whether the Bank will opt for another 50 basis point increase – their choice at the November meeting – which would take borrowing costs to four per cent, a post-financial crisis high.

But, some said rate cuts could come as soon as early next year due to core inflation falling rapidly in 2023.

“Core CPI inflation will be within touching distance of two per cent by the end of this year. If so, the MPC’s fears about ingrained high inflation should fade as 2023 progresses, bringing rate cuts into play in early 2024,” Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said.

Bailey and co climbed down from their 75 basis point increase in October at their last meeting.