Ignore the chancellor, we don’t need Chequers to end austerity

I generally presume cynicism in politicians’ arguments.

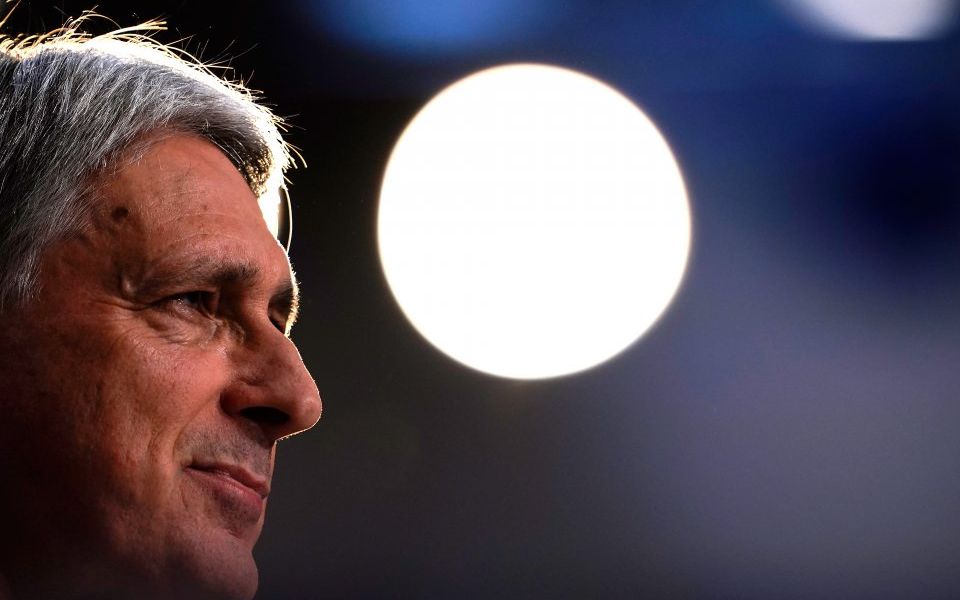

But Philip Hammond implying a Chequers-style relationship with the EU is needed to “end austerity” was shocking in its brazenness.

Ahead of the October Budget, the chancellor has echoed Theresa May in suggesting that looser government spending is just around the corner. Their calculation seems to be that voters truly desire ending fiscal constraint.

Read more: Hammond predicts economy boost from 'Brexit dividend'

Conveniently from a political perspective, Hammond has said that the close EU relationship the government desires is crucial to delivering this higher spending.

A successful negotiated Brexit deal, he said, would lead to stronger growth forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), allowing the government to achieve its fiscal targets while spending more in the coming five years.

Avoiding the spectre of a no-deal Brexit would furthermore allow the chancellor to release the “fiscal buffer” he had built up for a no-deal scenario. With a stronger growth outlook and no need to budget for contingencies, Hammond says that there would be a supposed double spending dividend from a Chequers-style deal.

First off, any decision to “end austerity” – meaning consolidation of the public finances – would be arbitrary in its timing.

Net borrowing adjusted for the economic cycle has fallen substantially since 2010, but it still stands at around two per cent of GDP – a level which would probably keep the debt-to-GDP ratio constant given economic growth, but would certainly not see debt fall back towards its historic norms.

UK government debt is still extraordinarily high. In the event of another major recession, it would jump to truly unprecedented levels for peacetime.

Worse, the longer-term public finance challenge associated with an ageing population looms just around the corner. On unchanged policies, the OBR forecasts that public sector net debt will rocket from around 85 per cent of GDP today to 380 per cent over the next 50 years.

This is unsustainable, and so won’t happen. Instead, the demands on healthcare and pension spending associated with changing demographics will require some combination of higher taxes or cuts to the spending baseline.

Any claim by politicians today that austerity is over is therefore either dishonest or misinformed.

What then of Hammond’s two “dividends”?

Once a deal is agreed, the UK should indeed see some bounce-back growth, as uncertainty is lifted and businesses begin making new investments in the knowledge of the new arrangements. But this rebound growth from more certainty would be temporary.

Though it might improve near-term growth forecasts, it would not represent a structural improvement in the public finances, and so cannot be used to justify new permanent spending.

The only mechanism through which a Brexit deal could theoretically improve the UK public finances permanently is if raises the long-term GDP potential of the economy. So we return to the classic debate about the long-term effects of Brexit, and the assumptions underpinning different models.

The Treasury view has long been that a no-deal scenario will be meaningfully worse than an ordinary free trade agreement. The leaked Cross Whitehall Briefing suggested a 7.7 per cent long-term hit to GDP with no deal (under WTO rules), and a 4.8 per cent contraction under a Canada-plus deal relative to EU membership.

The government has failed to release the detailed analysis and assumptions of this work, despite over 60 MPs demanding that it does so just last weekend.

Crucially, though, few believe that the UK will have no trade deal with the EU in the long term. Most Brexiteers want a Canada-style free trade agreement – something EU negotiators have stated is on the table, provided that solutions to the Irish border question can be agreed.

It is incredible to suggest that Chequers will deliver some fiscal bonanza through higher growth above and beyond what an extensive free trade agreement would deliver.

For this particular chancellor to hang so much on small changes to growth forecasts is especially galling.

Hammond has suggested in the past that Britain’s main economic problems are homegrown, and little to do with EU policy.

Yet faced with sustained low potential growth rates, he has done virtually nothing to try to improve prospects through tax reform, land-use planning reform, or other serious deregulatory measures.

Appealing to MPs to support Chequers to “end austerity” therefore rings hollow.

Britain’s long-term fiscal challenge remains daunting. Minor changes to long-term growth brought about by differences between Chequers and a Canada-plus agreement do little to change that. And using a temporary growth bounceback to justify permanent spending is irresponsible.

The government might have decided that it wants to open the spending taps. It should not pretend that this is conditional on May’s desired form of Brexit.

Read more: End of austerity not 'compatible' with eliminating deficit says IFS