If we don’t embrace a more flexible approach to carbon removal, the UK will lose out to the rest of the world

Carbon removal technologies will be key to start reversing the climate crisis. But the UK needs the right frameworks and the right kind of investment to become a leader in this space, writes Brennan Spellacy

It’s now almost inevitable we’ll cross the 1.5°C threshold, according to the latest reports. It will happen in the 2030s – even under very ambitious climate policies.

The problem with these findings is they tend to lead to something akin to public despair. People feel there’s nothing left to do if the fate of our planet is already written. Instead, it should motivate us to push even harder, as every fraction of a degree of warming we avoid will help to mitigate harm to the most vulnerable populations.

Using technology to remove carbon from the atmosphere can help us achieve that. If we can scale both nature-based and engineered approaches to about 10 billion tonnes of removal by 2050, we can make significant progress to rebalance the planet in the long term. But we’re currently only durably removing and storing about 2 million tonnes each year. We need to accelerate 5,000 times over in less than 30 years.

To unlock significant capital to scale these climate solutions, we need both public and private sectors working together.

There has already been a tremendous influx of investment from the private sector. Ninety-six percent of Britain’s FTSE 350 companies have increased their expenditure on carbon credits over the past 24 months. Nearly half intend to dramatically increase spending again over the next two years.

There is a global race to the top underway on climate innovation, and the UK risks falling behind as other countries are making bolder investments.

In the US, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) along with the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the CHIPS and Science Act have committed over £410bn to climate solutions over the next 10 years. These investments will spur unprecedented growth – not just in the climate sector, but throughout the American economy. Similarly, the EU has tabled a Green Deal Industrial Plan aimed at enhancing the competitiveness of Europe’s net-zero industry.

Many observers were disappointed with the last UK’s budget, with critics claiming it was a missed opportunity to create a green economy. Similarly, the UK’s Net Zero Review fell short on any specifics to support this new infrastructure.

The Green Finance Strategy, released months ago, asserted the UK will become the world’s first “net-zero financial centre.” As one of the world’s foremost financial hubs, the UK has the potential to open the spigot of climate investment, with British companies poised to convert that capital into the jobs of the future. The upcoming consultation on methods to mobilise finance through high-integrity voluntary markets will be paramount in achieving this goal.

But the scale of investment isn’t the only hurdle in the way of the UK. Regulations are already directing climate tech companies toward more agile countries.

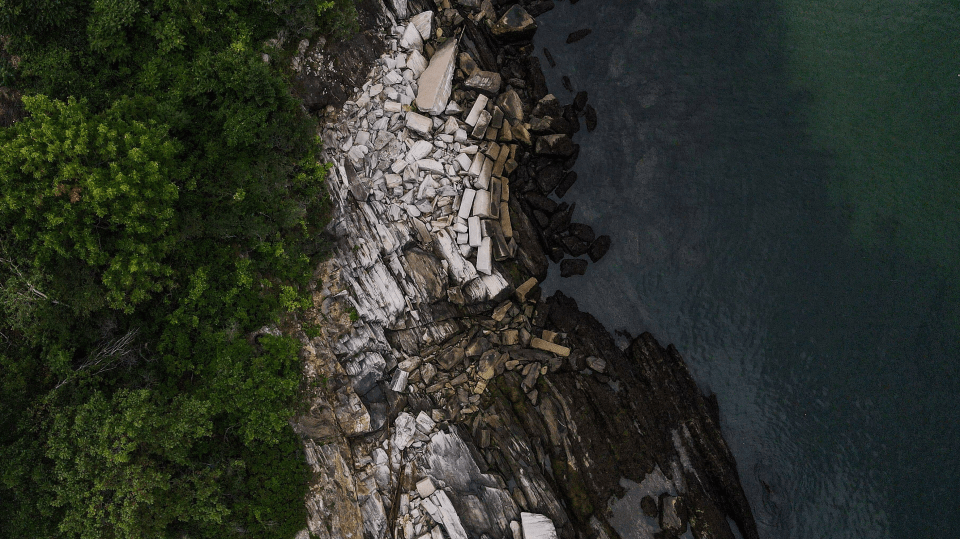

I’ll give you an example. Our partner, Running Tide, is piloting its multi-pathway carbon removal system in Iceland rather than the US or UK, partly because of restrictive interpretation of international laws like the London Protocol, which was written to prevent the disposal of waste at sea, before climate change or carbon dioxide pollution was an acknowledged problem. This restrictive interpretation is being used to hinder research and development of positive interventions in the ocean. Effectively, there is a framework for cruise ships to dump human waste into the ocean, but novel ocean-based carbon removal technologies like Running Tide’s are restricted.

Iceland, a country of less than 400,000 people and just over £20bn in GDP, can attract the most cutting-edge projects thanks to a flexible and innovative approach to permitting.

Imagine the strides the UK could take with an all-in approach to a net zero economy.

Private companies have a chance to blaze a trail ahead of government spending by proving the effectiveness of innovative carbon removal methods and reducing the risk to public funds. The government must then follow with the capital investments necessary to fuel these approaches to the scale required for ensuring a liveable future.