How will the Bank of England change its approach on interest rates after wage growth falls again?

The Bank of England’s most recent economic forecasts, which justified its higher-for-longer narrative on the interest rate, look increasingly out of date after new figures were published on the state of the labour market.

The forecasts, made in November, suggested that pay growth would end the year around 7.2 per cent. This morning, however, official figures showed that total pay growth came in comfortably below those forecasts at 6.5 per cent.

Annual wage growth of 6.5 per cent may still sound like a lot, but a look underneath the hood suggests that wage growth is slowing fast.

Although the start of the year saw rapid wage growth, Hannah Slaughter, senior economist at the Resolution Foundation, said there has been “barely any” growth in pay since the summer.

Looking specifically over the last three months, private sector regular pay growth fell to 2.6 per cent on an annualised basis, more or less consistent with the Bank’s target. In other words, the headline rate of 6.5 per cent was distorted by very strong wage growth earlier in 2023.

“This means that annual pay growth will continue to fall in early 2024 – and is no longer fuelling inflation,” Slaughter commented.

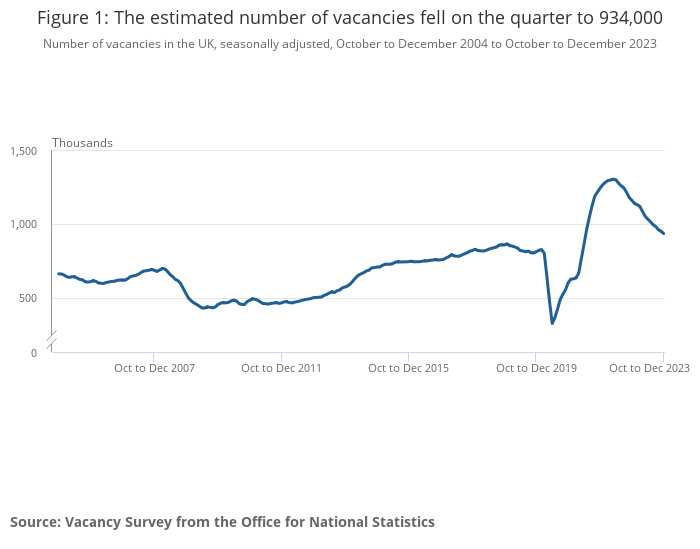

The figures also showed that the number of vacancies fell for the 18th consecutive quarter, the longest consecutive fall on record, while the number of payrolled employees also dipped. Neither fell by much, but the picture is fairly clear: slowly but surely the labour market is loosening.

It’s worth remembering why we are paying so much attention to developments in the labour market.

In its November forecast, the Bank predicted inflation would only fall below two per cent by the end of next year. The main reason for the persistence in inflation, the forecast said, was the continuing tightness of the labour market, which would fuel strong wage growth.

As a result, domestic inflationary pressures would remain frustratingly persistent across this year and next.

But if those forecasts need adjusting to reflect a loosening in the labour market, the obvious question is how the Bank of England should change its policy.

Martin Beck, chief economic adviser to EY Item Club said: “The latest pay numbers make it even more likely that the MPC will move away from ‘high for longer’ rhetoric when it meets next month”.

That’s not to say that it will lower interest rates in February, but it may prepare the ground for such a move. So far, rate-setters have insisted at every turn that it is “too early” to discuss cutting rates.

The change will be nuanced, however.

Despite the developments seen over the past few months, the labour market remains tight in historical terms.

Experimental estimates suggest that the unemployment rate remains at 4.2 per cent, which is actually below the Bank’s November forecast. And even after the longest consecutive fall in vacancies on record, there are still more vacancies than pre-COVID.

“The tightness of the labour market will probably mean that the Bank of England maintains its hawkish bias at its policy meeting in February,” Ashley Webb, UK economist at Capital Economics said.