How ‘twin deficits’ have fuelled turmoil in the gilt market

The gilt market has suffered a tumultuous start to the year, with investors taking fright at UK government debt and yields surging to the highest level in decades.

The sell-off eased slightly on Wednesday following positive inflation figures, but the rate paid on government bonds remains well ahead of where it was just a few weeks ago.

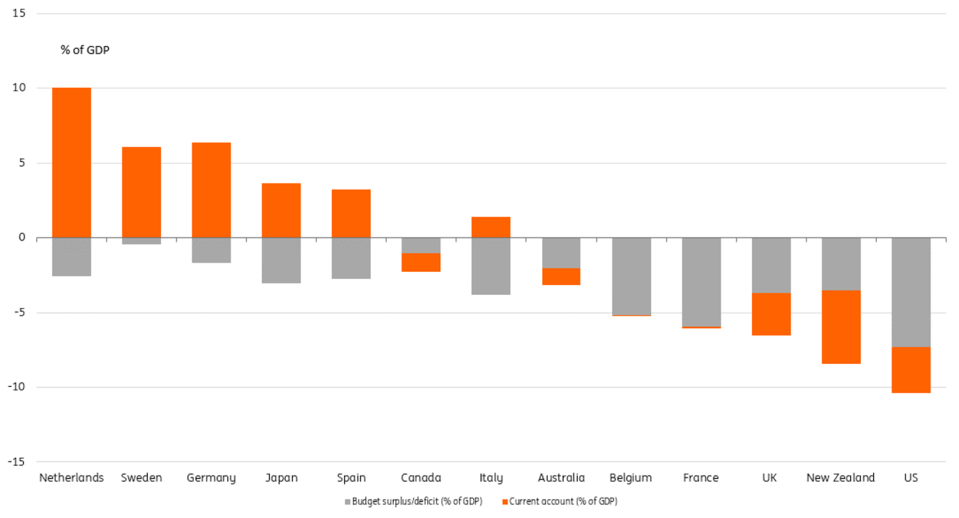

A number of analysts have pointed to the UK’s ‘twin deficits’ as a central driver of the turmoil. In effect, these help explain why the UK has been more exposed to international market movements than other similar economies.

So what are these two deficits, and why are they intensifying pressure in the gilt market?

The first is simply the fiscal deficit, the difference between government expenditure and tax receipts.

A deficit implies the government is pumping more money into the economy than it is taking out, funded through extra borrowing, which increases demand and adds to inflationary pressures.

This has been a concern for investors in the wake of the Budget, primarily because the government has increased public spending by around £70bn every year for the next five years.

Forecasts suggest the Budget will push up inflation by 0.5 percentage points, although early indications suggest the impact might be bigger.

Investors will want a premium to protect against the risk of inflation.

A growing deficit can also make investors nervy because it implies the need for extra borrowing now and – in the absence of economic growth – tax rises or spending cuts in the indeterminate future.

Investors may start to think the government is not as serious about paying back the debt, and so demand a higher interest rate.

Worries about fiscal deficits have climbed up the agenda recently due to mounting levels of debt and anaemic growth (with the exception of the US).

The combination of high debt, high interest rates and slow growth makes a particularly toxic combination and increases the risk of an ever spiralling debt pile.

But many advanced economies have a fiscal deficit. Indeed, at 4.4 per cent of GDP in the 2023/24 fiscal year, the UK is by no means the worst offender on this front.

According to the IMF’s latest projections, the UK’s deficit will be 3.7 per cent of GDP. That’s the same as Italy, better than France at 5.9 per cent of GDP and significantly better than the US at 7.3 per cent.

And this is where the second deficit – a current account deficit – comes into play.

A current account deficit implies that the UK is essentially borrowing more from abroad than it lends. Why does this matter?

“The argument goes that with twin deficits, you’re reliant ‘on the kindness of strangers’ to lend money to you – and in that case you’ve got to look an attractive investment proposition or offer enough compensation in terms of interest rates,” Chris Turner, an FX analyst at ING, says.

Around 30 per cent of gilts are held abroad, according to Deutsche Bank. So, if the investment case is not looking good, interest rates – gilt yields – will have to rise.

It is fair to say there’s some uncertainty about the outlook for the UK. The economy has been stagnant since the middle of last year and business confidence has plummeted thanks to the Budget. The investment case, therefore, is not entirely appealing.

The prospect of Trump’s second presidency has also spooked markets, which leaves the UK exposed if investors just want to hold safer assets.

“When global risk sentiment declines, the UK is more vulnerable to funds flowing to safer shores,” Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics said.

George Saravelos, an analyst at Deutsche Bank, added that the “marginal price setter” of the value of gilts was the yield on US Treasuries, rather than domestic policy considerations.

“The more a country relies on foreign financing for its domestic debt issuance, the more exposed it is to the global environment,” he said.