How Robert Mugabe brought Zimbabwe’s economy to its knees

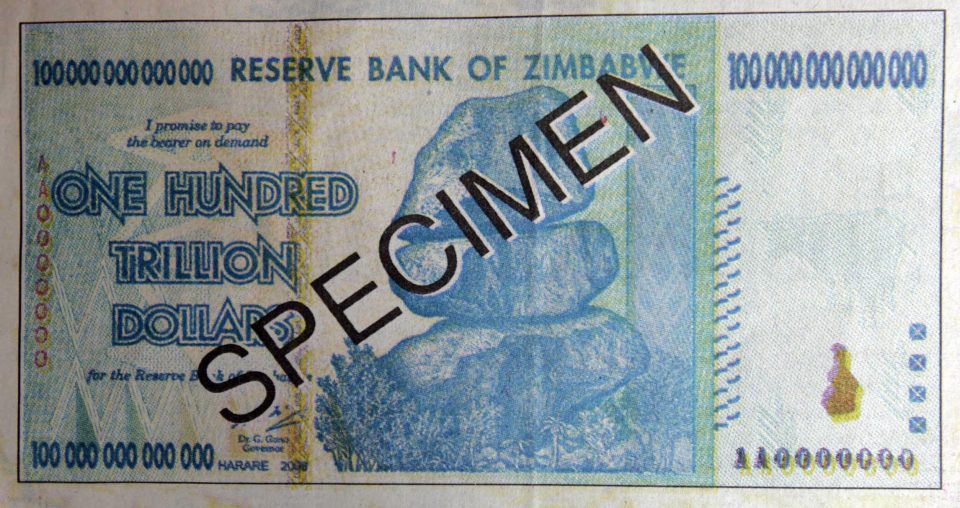

In the United States, a $100 trillion dollar note would be worth more than five-times the country’s GDP. But at one stage in Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe it would barely get you a loaf of bread.

Zimbabwe’s 100 trillion dollar note had the most zeros of any legal tender on the planet. That reads: $100,000,000,000,000.

It became emblematic of the economic crisis which dogged the country for 37 years under Mugabe, whose death was announced this morning.

Read more: Former Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe dies aged 95

How did it get to that stage?

When he was elected in 1980, Mugabe inherited a country brimming with potential.

A healthy supply of rain helped farming outputs, giving Zimbabwe a growth rate higher than the rest of sub-Saharan Africa as a whole.

But a drought early in his rule coupled with a global recession pushed down commodity export prices. In turn, Mugabe in place economic policies that allowed for an open market economy in the 1990s, based around Zimbabwe’s manufacturing industry.

However, the sector could not keep up with foreign competition. Industrial output was around a quarter of GDP in the early 1990s, but has since dropped to less than one-tenth.

Land reforms

At the turn of the century, Mugabe put in place a controversial land reform policy, which was central to his reelection campaigns in 2002 and 2008.

Most of the country’s 4,000 white farmers, a key part of its agricultural economy, were forced from their land – often violently – in favour of around 1m black Zimbabweans.

Critics accused him of bribing voters, but Mugabe billed the measures as an attempt to put right Zimbabwe’s colonial legacy that left vast swathes of land in the hands of a white minority.

The result? Real GDP fell 45 per cent in the ten years to 2009, while farm production collapsed.

The price of war and unrest

During the 1990s, civil unrest broke out across the country as a result of the economic stagnation. In 1992, police curtailed trade union rights to protest against the government.

But after several years of unrest which saw civil servants, nurses, and junior doctors go on strike over pay, the country descended into a full-scale national strike.

Mugabe’s answer was to pay off those he was most threatened by: war veterans of the 1970s and 1980s. He agreed to pay them large gratuities and pensions – something Zimbabwe could not afford to do.

To make matters worse, the country then waded into a bloody war in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1998. That is said to have cost the country nearly six billion Zimbabwean dollars, and helped accelerate a slide into currency collapse over the next decade.

Read more: How the fall of Mugabe allowed Zimbabwe to reclaim the future of its tourism

Hyperinflation

By 2006, Zimbabwe’s annual inflation had risen above 1,000 per cent. While the global economy was still booming before the financial crisis, Zimbabweans were hauling wheelbarrows of cash to stores for basic supplies.

In 2009, the currency had reached breaking point, with the 100 trillion dollar bill entering circulation. Price controls on goods led to a rush on shops to buy the vastly cheaper products. Manufacturers’ products dried up as a result, and many went out of business.

Eventually, Zimbabwe abandoned its own dollar in favour of the US dollar. This initially stabilised the economy, and incomes rebounded 40 per cent – but by the time Mugabe left office, this had flatlined.

Gallery

Mugabe with Tony Blair in 1997 (Getty)

(Getty)

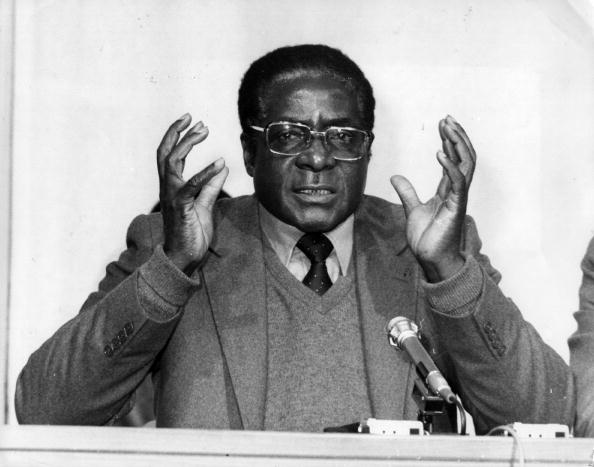

Mugabe speaks at a press conference in March 1980 (Getty)

Mugabe arrives at Lancaster House in London in 1979 to sign a ceasefire on the country’s civil war (Getty)

(Getty)

Zimbabwe’s one hundred trillion dollar note (Getty)