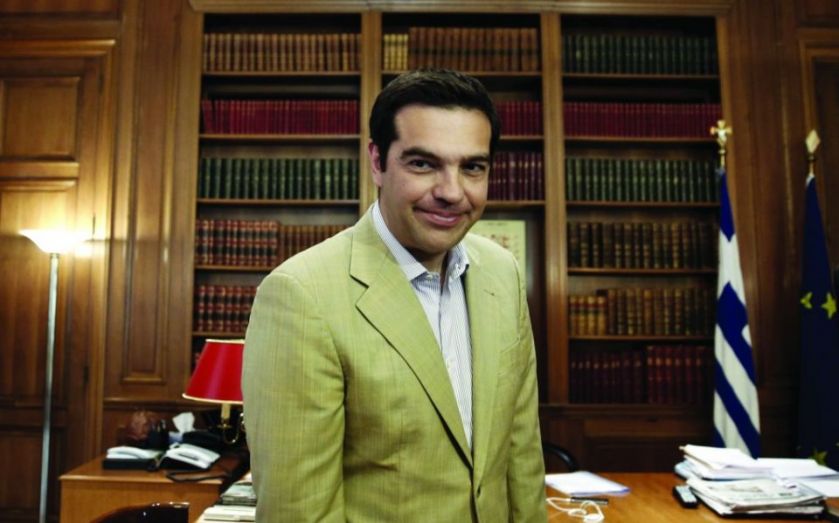

Alexis Tsipras faces backlash as bankers insist euro would not be harmed by Grexit

World leaders piled pressure on Greece yesterday by calling for the indebted country to accept unpopular reforms, with Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras striking an increasingly isolated figure.

From the picturesque alpine resort that played host to this week’s G7 meeting, US President Barack Obama and German Chancellor Angela Merkel insisted that Greece must accept tough reforms proposed by its creditors.

Meanwhile other politicians and central bankers turned the heat on Greece by saying that the rest of the Eurozone will be unharmed if it crashes out of the bloc.

Yet Greece’s government remains defiant, with one official lashing out at the state’s critics. “From Obama, to Merkel, to [Jean-Claude] Juncker, to [Wolfgang] Schaeuble, they all say ‘Greece needs to do more reforms’ and ‘to put in more effort’. They’re so obnoxious. If only they knew how distasteful they look to a Greek audience,” the official told City A.M.

“They’re all embarrassed. They all expected Tsipras to have folded, but he hasn’t and this makes them very angry. And they know Greece’s liquidity crisis is not the fault of the government, but those bastards who want to build the new holy German empire.”

Earlier in the day, Merkel had warned that “solidarity between European countries and with Greece means Greece will have to implement measures”.

Obama, also speaking at the G7, added: “The Greeks are going to have to follow through and make some tough political choices that will be good for them long-term.”

French finance minister Michel Sapin, who had been perceived as an ally of Greece, shrugged off the consequences of a so-called Grexit. “It would be no drama for us to see Greece leaving the euro,” Sapin said yesterday. “It would not be serious from a financial or economic point of view.”

His comments were echoed by European Central Bank officials Christian Noyer and Ewald Nowotny, who both played down the prospect of contagion, should Greece crash out of the Eurozone. The Greeks only have “a matter of days” to come to an agreement with lenders, Noyer said.

The widespread warnings came just a day after EU boss Jean-Claude Juncker, who had appeared to be sympathetic towards the Greek government’s arguments, lashed out at its Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras for failing to submit a new plan for a bailout deal.

“Tsipras, my friend, had promised that by Thursday evening, he would present a second alternative proposal. Then he said he would present it on Friday. Then he said he would call on Saturday. But I have never received this alternative proposal,” Juncker said on Sunday.

Meanwhile Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis tried to tackle the reasons behind the deadlock with a defiant speech delivered in Germany yesterday.

Varoufakis argued that he has attempted to overhaul the current bailout programme, and said he had received “private” backing from other Eurozone officials, but that it was “politically” difficult.

In a relatively conciliatory speech, Varoufakis accepted that Greece needs reform, but said that creditors are focusing on the wrong kind of reforms. The budget surplus demanded of Greece is too high, he said, arguing that it would harm the private sector. He also hit out at calls to cut pensions and deregulate the labour market.

“If you continue to squeeze our population into misery, we will not be reformable ever,” he told an event in Berlin organised by the Hans Boeckler Foundation. Varoufakis called on Merkel to deliver a speech of hope in Greece that would jump-start the search for a new deal.

“A speech of hope for growth does not have to be technical, it simply has to mark a break from five years of adding new loans on already unsustainable debt on condition of more doses of punitive austerity that diminishes our incomes,” the finance minister said.

“Who should deliver this speech of hope? Well I think it should be the German Chancellor.”

Opinion polls suggest the Greek public are willing to accept some compromises in order to secure a deal. A poll by the University of Macedonia indicated that just 16 per cent wanted to leave the euro, while 51.5 per cent feared it could happen.