House prices are poised to slide in 2023 but straight into the hands of the lucky few

There’s a pretty wild variety of house price predictions doing the rounds.

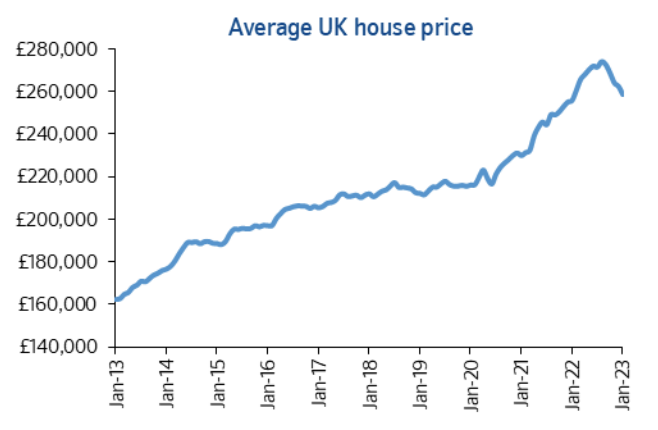

Capital Economics have forecast they could fall 12 per cent, while experts at property search site Zoopla are a bit more optimistic. The consensus seems to be somewhere around a six per cent fall in 2023.

One thing is certain: house prices are going to fall, but by how much probably depends on whether the UK economy outperforms all the gloomy predictions dominating the headlines.

The drop is a natural response to a huge change in the underlying factors determining how the market sets prices.

Interest rates have been jolted upwards after resting at rock bottom levels for more than decade.

The Bank of England has been forced to kick them higher ten times in a row to four per cent from 0.1 per cent to tame the worst inflation crunch in 40 years.

That has raised rates on international financial markets for UK debt, which mortgage providers use to price their products. Those lenders have passed these on to protect their margins.

There’s still a big hangover from Liz Truss’s ill-fated mini budget in September, mind. Damn those lefty bond markets.

While yields on UK gilts are back around 3.5 per cent, rates on the average 2-year and 5-year mortgage are still far above five per cent.

All this means potential buyers are pausing on purchases because they’re worried about being saddled with debt at the current market interest rate.

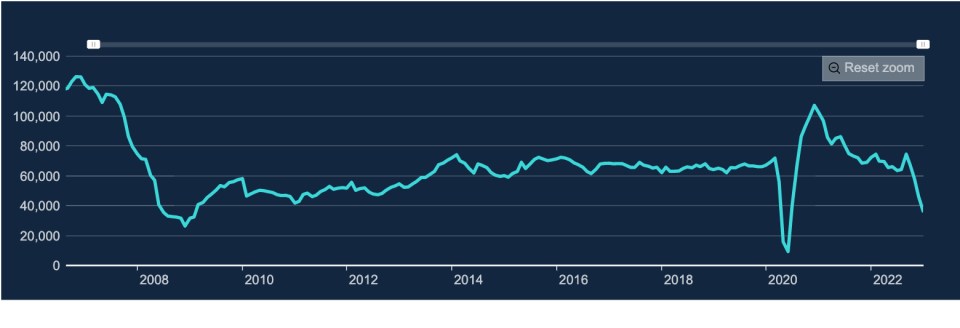

Mortgage approvals have tumbled to financial crisis lows (excluding the pandemic)

UK house prices have already started tumbling

Demand is being sapped from the housing market. Sellers will have to drop prices to find buyers. Average house prices will fall.

Rate cuts aren’t likely to land until Christmas at the very earliest, so buyer caution is probably going to be a feature for the rest of the year.

The UK economy is highly sensitive to changes in the housing market, and the effects of those changes are amplified via a few channels.

One of which is something called “wealth effects” in economics. When house prices fall, all else equal, homeowners experience a drop in the value of their total stock assets, or wealth. The opposite happens when prices rise.

As a result, they often respond by reducing spending. They feel like they’re getting worse off – and they are – so they respond with greater financial caution.

This response impacts high street shops, pubs, bars, restaurants, the so-called “real economy”.

Retail sales figures from the Office for National Statistics, Barclays and the British Retail Consortium are all softening, possibly caused in part by the negative wealth effect filtering down to consumers.

On the business side, if house prices are expected to fall, “housebuilders will curb the commencement of new projects, while fewer homeowners will renovate or extend their properties,” according to Pantheon Macroeconoimcs’s Samuel Tombs, both of which would hit GDP.

On top of the biggest real income squeeze on record, the drop in house prices is poised to magnify a concoction of negative shocks that will push the UK economy into recession.

But there’s an opportunity on the horizon.

Last week, Threadneedle Street’s economists said inflation will more than halve by the end of the year. With the economy possibly still in recession, there is a chance the Bank cuts borrowing costs. That’s also what investors think will happen.

At that point, house prices could be at the trough of their slump.

Coincided with a rate cut, affordability will improve, luring buyers back to the market. Some lenders are already trying to seize on that future demand. Virgin money will lend you money at 3.99 per cent if you’ve a 25 per cent deposit.

For the patient among us – and those lucky enough to still be endowed with a mass of savings built up during the pandemic – homeownership may not be such a distant pipe dream.

WHAT I’M READING

The Bank of England’s reaction function over the coming year is not going to be marked out in definable thresholds like its former chief Mark Carney did several years ago, according to Capital Economics. The former Canadian banker said in 2013/14 UK rates would rise when the unemployment rate dropped below a threshold of seven per cent. They stayed at historic lows until 2021.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

The percentage point gremlin will be after this offender in full force very soon after it sees this passage:

“The day before the mini-Budget, the Bank of England raised interest rates by 0.5 per cent, whereas the US Federal Reserve had just announced a third successive rate rise of 0.75 per cent. In addition, the Bank simultaneously confirmed plans for a bond-selling programme. Bond prices fell sharply, putting pension funds under pressure.”

Can you guess the offender? Email: jack.barnett@cityam.com.