‘Hideous, extreme greed’: Why disasters keep happening at Boeing

“The eyes of the world are on us,” Boeing’s chief executive Dave Calhoun said on Monday, as the embattled planemaker announced that he, along with many of the firm’s C-suite executives, would be stepping down as part of its largest management reshuffle in years.

The move comes as Boeing grapples with one of the biggest crises in its history, which was sparked in January after an emergency exit door fell off an Alaska Airlines flight midair.

Hundreds of Boeing planes have since been grounded, and the firm is now under scrutiny from regulators, the US Department of Justice and the FBI.

Its customers are unhappy too. In an uncommon show of frustration, some of Boeing’s biggest airline buyers demanded a meeting with the company’s board of directors, days before the top brass shake-up.

Shares are down almost 25 per cent since the turn of the year, while shares in rival Airbus are up over 22 per cent.

Onlookers would be forgiven for thinking this was the lowest point in the company’s history, but it has been here before.

Calhoun replaced Dennis Muilenburg as CEO after two fatal 737 Max crashes – one in Ethiopia in 2018 and one in Indonesia in 2019 – which resulted in a combined total of 346 passengers being killed. While they were different models than the 737 Max-9 used by Alaska Airlines, this will offer little comfort to investors or the public.

Another major accident could prove disastrous for the firm’s reputation, which has already been suffering as a result of delivery delays caused by production problems in its supply chains.

But analysts and industry experts are clear that Boeing won’t be able to recover until it sorts out its core problem – its culture.

Corporate culture

A string of whistleblowers have emerged to claim the high pressure placed on its employees has led to sub-standard parts being fitted to its aircraft.

“There is this broader cultural problem, where the management have had to put people under pressure… where the goal is keeping to the schedule and not producing things that are as good as they could be, or as good as they should be,” Dai Whittingham, chief executive of the UK Flight Safety Committee, told City A.M.

John Barnett, a former quality manager at the company who became a whistleblower, has claimed workers had removed parts from scrap bins and fitted them to planes to prevent delays on the production line – allegations Boeing strongly denies.

His recent death has only added to the drama engulfing the company.

Some trace the cultural problems back to Boeing’s 1997 acquisition of McDonnell Douglas, whose leaders took over the company and prioritised cost control over quality.

But veteran aerospace analyst Richard Aboulafia believes it began in the mid 2000s, when a “Jack Welch” culture took over – a reference to the former boss of General Electric, who was considered a master in squeezing as much money from any business as possible.

“I don’t think it’s complacency. I think it’s hideous, extreme greed,” he said.

“I don’t think it’s complacency. I think it’s hideous, extreme greed.”

Richard Aboulafia, managing director of Aerodynamic Advisory

“There is no way to accurately and quickly relay technical and manufacturing needs to senior management, that ability to speak up and say, ‘hey, we don’t have enough time or resources to do this’… and to see management engage in operations, rather than just presenting financial abstractions,” he told City A.M.

Boeing pointed City A.M. to a recent interview with Calhoun, where he vowed to improve the company’s culture going forward.

Prior to Monday’s board reshuffle, Aboulafia argued most of the senior management and the board needed to exit to kick start any turnaround.

His view is that Calhoun’s replacement should be a technical expert, an opinion backed by the head of Emirates Sir Tim Clark, who on Tuesday argued any new boss must have a strong engineering background.

Steve Mollenkopf, the ex-Qualcomm chief taking over as chair, will lead the search for the next chief executive. General Electric boss Larry Culp, Spirit AeroSystem’s Pat Shanahan and Carrier chairman David Gitlin, who sits on Boeing’s board, have all been named as possible contenders.

Analysts are divided, however, on whether the Boeing shake-up will work. The company is effectively in limbo until Calhoun leaves at the end of 2024 and changes in the past have solved little.

“It’s not surprising there appears to be some scepticism, given previous executive merry go-rounds appear to have made no difference and the company has slid into further chaos,” Susannah Streeter, head of money and markets at Hargreaves Lansdown, told City A.M.

And there are other issues the new management will need to resolve. Both Boeing and Airbus have been grappling with production problems at major suppliers, namely Belfast-based Spirit AeroSystems, which built the door that blew out during the Alaska Airlines flight.

Regulations place the onus on the planemaker’s to audit any problems at subcontractors and Boeing, unlike its rival, has been criticised for sub-par checks.

While the high-profile incidents with Boeing planes have been serious and attracted much media attention, it is worth noting that both Boeing and Airbus planes have faced a similar number of problems.

There were 545 significant safety incidents involving Boeing in 2023/24 and 515 involving Airbus, per analysis from Airline Ratings, findings which level out given there are more Boeing planes in the air.

Could Boeing collapse?

The short answer is no, analysts say. Boeing is simply too big and too tied-up with the US government to totally fail any time in the near future.

On top of its commercial airplanes division, Boeing is the fourth largest defence contractor in the world and is also deeply involved in space technology.

But there is a possibility the Virginia-headquartered firm could lose its place as Airbus’s closest planemaking competitor, breaking a duopoly that has existed for decades.

“I think a lot of eyes are turning to Embraer because they’re highly competent. They just need to find a way to scale up,” Aboulafia said.

Embraer has its headquarters in Brazil’s São José dos Campos and is currently the third largest producer of civil aircraft in the world. It would relish the opportunity to pile pressure on Boeing.

“Given all the current trends, Boeing’s mismanagement and market needs, Embraer can get there with the right strategy and the right leadership…. The first step is to challenge part or all of the 737,” Aboulafia added, noting that “would take a decade.”

The battle will be heavily influenced by the performance of Boeing’s narrowbody (single-aisle) 737 Max (Airbus’s equivalent is the bestselling A320).

And it has certainly been losing ground over the last decade.

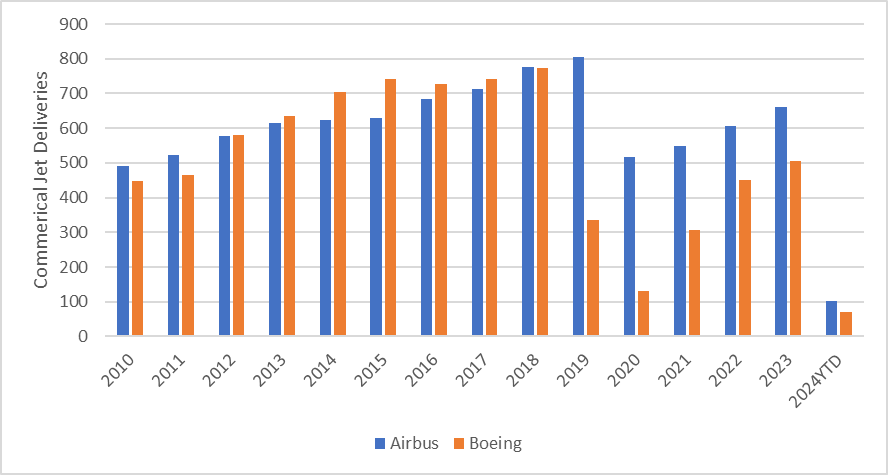

Data shared with City A.M. by consultancy Cirium Ascend shows Airbus consistently trending ahead of Boeing in deliveries, market share, and commercial jet orders.

“Deliveries show Boeing with marginally greater than 50 per cent market share in the middle of the last decade, as they matched Airbus single-aisle output but led in the twin-aisle space,” Rob Morris, Cirium’s global head, told City A.M.

“That share dislocated in 2019 when Boeing was forced to suspend 737 Max deliveries on early March after the type certificate was suspended by FAA and all other authorities globally.

“Overall volumes fell during the pandemic but Airbus was able to maintain all production lines, whilst Boeing has suffered ongoing production quality issues on both 737 and 787 lines, which has resulted in Airbus’s more than 60 per cent market share annually since then.”

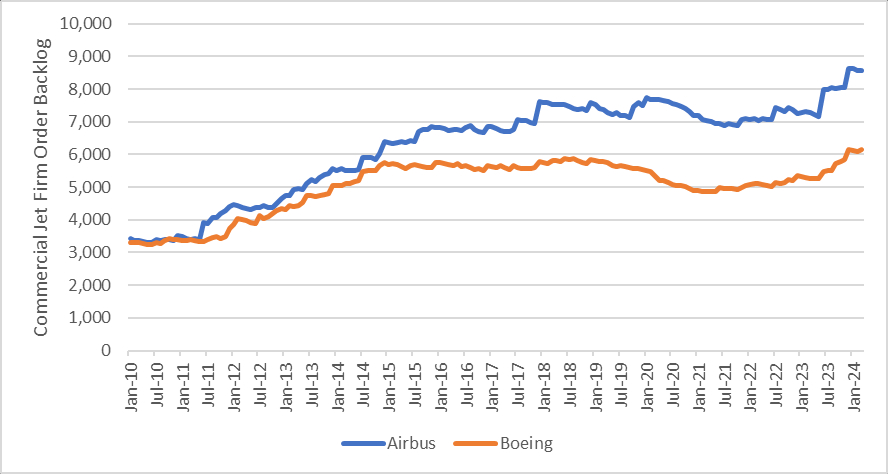

The order backlog of both company’s paints a similar picture.

“Airbus and Boeing held a roughly 50/50 backlog split through 2015, [but] Airbus started to move ahead to the point where today the backlog is 60 per cent in their favour, driven largely by the high volume single-aisle, A320 family,” Morris said.

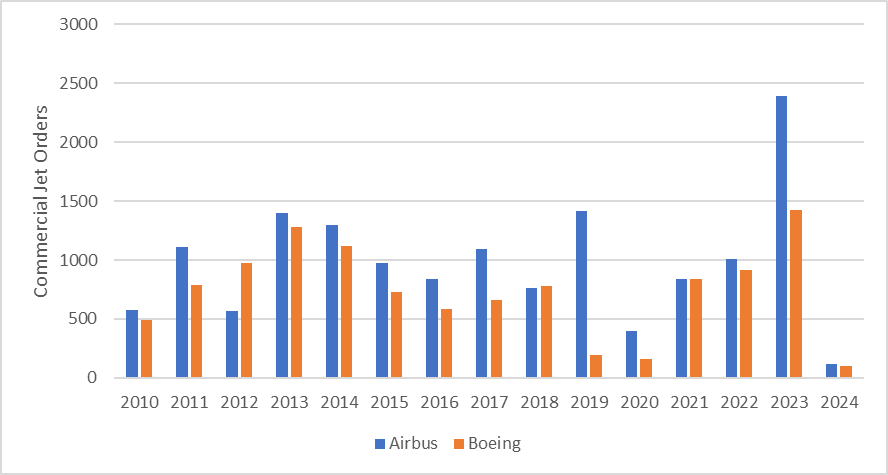

And Boeing has also fallen further behind its long running rival on commercial jet orders over the last decade. The gaps in 2019 and 2023, the two years following the fatal crashes that weren’t affected by Covid-19, were particularly steep.

The figures aren’t pretty.

The latest incidents have undoubtedly hit Boeing’s reputation hard and it has a huge mountain to climb to ensure it doesn’t slip further behind Airbus.

A criminal investigation into the Alaska Airlines incident has yet to conclude, and airlines are steadily losing faith. It was revealed in February that a gap in deliveries caused by 737 Max delays had led Boeing’s biggest customer, United Airlines, to start talks with Airbus for more jets.

More turbulence is on the horizon.