Labour should increase pension contributions to get the UK economy going again

In the first few weeks in office Labour has announced a number of different policies that Rachel Reeves hopes will get the British economy firing on all cylinders again.

One policy that has received less attention – a review into pension adequacy – suggests that important changes might be on the way, changes which would support the Chancellor’s ambition to create a high investment economy.

The big question for this review will be whether auto-enrolment pension contributions should be increased. Currently, the minimum contribution for these pensions is split, with employers paying at least three per cent and the employee the remaining five per cent.

Increasing pension contributions would, in effect, be an attempt by the government to encourage a higher savings rate. This would make an important contribution in fixing one of the UK’s most persistent problems: low levels of private sector investment.

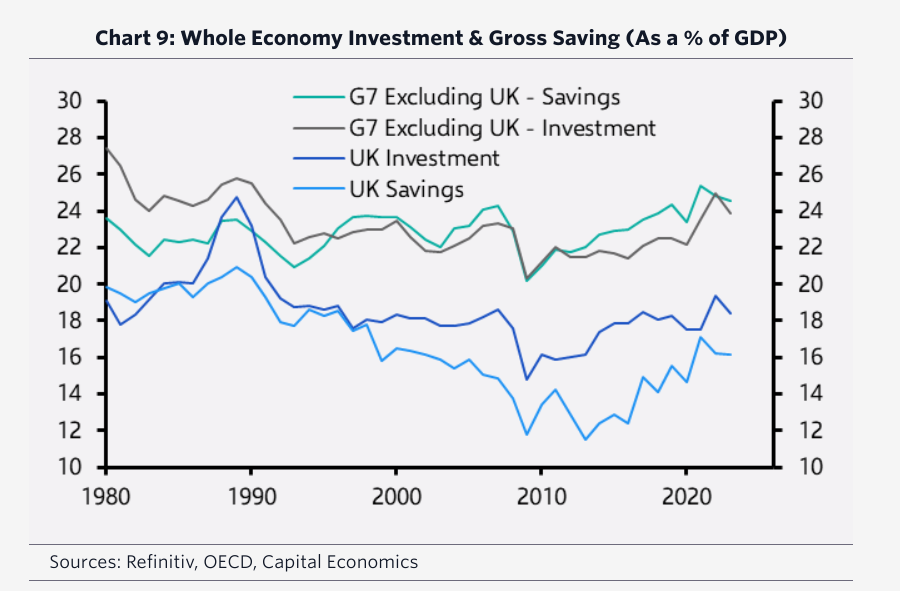

In 2022, private investment in the UK was the lowest among G7 economies, according to IPPR. This was the third successive year in which the UK ranked bottom among the world’s richest economies in terms of investment.

Governments of all stripes have talked up their ambition to lift levels of private sector investment, which is a sensible ambition. But investments must be paid for, so any government looking to increase investment must ask how it will be funded.

This is where pension contributions come in. Investments can either be funded through domestic savings or by increasing borrowing from abroad, which would mean running a larger current account deficit.

The current account records the net value of an economy’s exports and imports as well as international transfers of capital. The UK has a large current account deficit, which averaged about four per cent of GDP over the past decade.

There are endless debates about the potential risks of a persistent current account deficit and there is clearly a danger that, eventually, investors lose faith in the ability of borrowers to repay their debts.

This is very unlikely in the short term, particularly if those investments help to fuel sustainable economic growth. Indeed, the government should actively try and attract foreign investment.

But if Labour is serious about pulling “every available lever” to increase investment – as it claimed in its manifesto – then lifting the domestic savings rate is a sensible option for a number of different reasons.

For a start, domestic savings is relatively low compared to other advanced economies, despite having spiked recently. According to Capital Economics, the average savings rate in the rest of the G7 was about 8.3 percentage points higher than in the UK between 2000 and 2022.

Countries with high levels of domestic savings tend to have higher rates of investment because global capital is not perfectly mobile. In other words, domestic capital is more likely to invest in domestic opportunities, even if there are better options elsewhere in the world.

Having a larger pool of domestic capital also aligns with Reeves’ ‘securonomics’ agenda, which seeks to reduce – where possible – unnecessary reliance on the vagaries of the global economy.

Again, this is not necessarily an either/or. The economy can be a more attractive place for international investors while also having higher levels of domestic investment. Both should be encouraged.

Looking more narrowly at pensions themselves, there’s good reason to think households are simply not saving enough to support themselves into retirement.

The Resolution Foundation estimates that over 80 per cent of families are not saving enough for an acceptable standard of living in retirement.

It therefore makes sense to encourage people to save more, although there’s clearly a lot of scope for debate about what the appropriate level should be.

The implication of financing investment through domestic savings is that household consumption will have to fall. This is because resources which could have been spent on other things will, in effect, be redirected into the government’s investment priorities. Less money for nice dinners and more for wind farms, for example.

This might be painful in the short term, but it will almost certainly help to put the UK economy on stronger foundations.