UK economy: Headache for Bank of England as wage growth accelerates

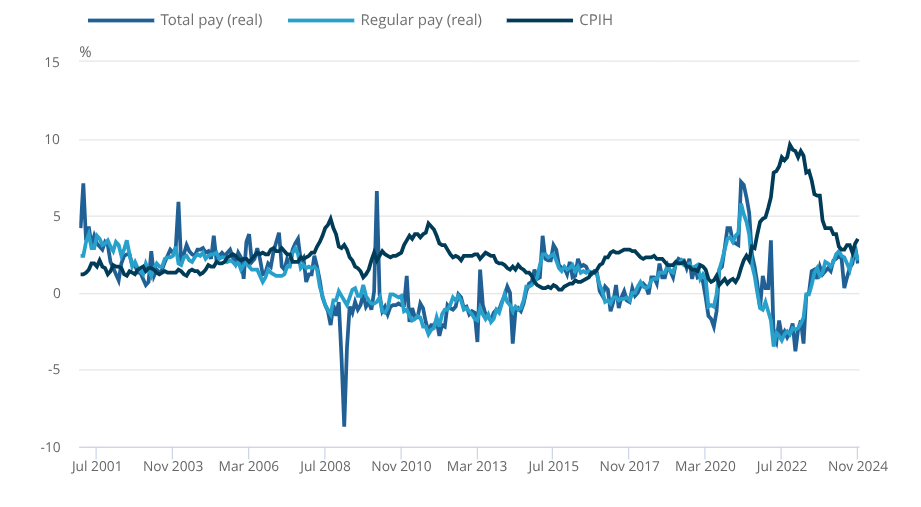

Wage growth picked up towards the end of last year, new figures show, revealing the continued persistence of price pressures in the UK economy.

According to figures released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), annual regular pay growth averaged 5.6 per cent in the three months to November, up from 5.2 per cent previously.

Total pay growth – which includes bonuses – hit 5.6 per cent in the same period, also up from 5.2 per cent.

“Pay growth picked up for a second consecutive period, again driven by strong increases in the private sector,” Liz McKeown, director of economic statistics at the ONS said.

Looking specifically at the private sector, pay growth hit 6.0 per cent, its highest level since February last year.

While the figures were roughly in line with City forecasts, the acceleration in pay growth suggests that inflationary pressures remain elevated and may restrain the pace of interest rate cuts.

“Earnings growth remains at a clip that is, clearly, incompatible with a sustainable return to the Bank of England’s two per cent inflation target over the medium-term,” Michael Brown, senior research strategist at Pepperstone said.

Still, most analysts expect the Bank to cut rates again in February, even if the pace of cuts may be slow thereafter.

“The Bank is unlikely to deviate from its gradualist approach while wage growth remains high,” Jack Kennedy, senior economist at Indeed said.

Unemployment, meanwhile, rose to 4.4 per cent from 4.3 per cent previously, in line with expectations.

Liz Kendall, Work and Pensions Secretary, said the figures were “more evidence that we must Get Britain Working”.

“This Government is relentlessly focused on driving up opportunity and driving down barriers to success in every part of the country,” she added.

The Bank of England is expected to cut interest rates just twice this year, in part due to the continued tightness of the labour market.

Policymakers only reduced borrowing costs twice last year, ensuring the benchmark Bank Rate – which stands at 4.75 per cent – remains in restrictive territory.

This means monetary policy is weighing on economic activity, which should contribute to a looser labour market and weaker pay growth in the months to come.

But some economists are concerned that the measures announced in the Budget might contribute to a more severe downturn in the jobs market.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves announced a £25bn increase in employers’ national insurance, lifting the rate to 15 per cent while also cutting the wage threshold at which firms start paying the levy.

Reeves also increased the minimum wage by 6.7 per cent, piling further costs on to employers’ balance sheets.

The latest labour market report showed that the number of employees on payroll fell by 11,000 in the three months to November.

An early estimate for December also suggested that the number of employees fell by 47,000 month-on-month. Although subject to revision, this brought the annual growth rate in employment down to 0 per cent, its weakest since April 2021.

In addition, there was another fall in vacancies, which fell for the 30th consecutive quarter.

McKeown said short-term movements in the figures should be treated with “caution” due to the ONS’s well-publicised data difficulties.

Jane Gratton, deputy director of public policy at the British Chambers of Commerce, said the impact of the tax changes will not be “fully seen” until later in the year.

“However, the warning lights on recruitment, employment and training are already flashing,” she said.