Has the euro’s time come to shine?

Our fixed income team thinks that after more than a decade of financial uncertainty, Europe’s fortunes – and that of the euro – could be set to change. Here’s why.

Years of instability

The past couple of years have brought yet more turmoil and uncertainty to the European Union. What its proponents see as a beacon of political and economic progress and stability, has often seemed anything but.

The years following the 2007-08 financial crisis, saw a series of crises around the, in some cases, dire public finances among southern European countries, notably Greece. The ramifications have continued to be felt and in recent years the spotlight fell on Italy, which elected a “populist”, anti-EU coalition whose spending proposals would have breached EU limits.

The UK’s 2016 referendum vote to leave the EU was a further blow to confidence. The multitude of questions over the terms and nature of the UK’s departure has been a running sore point for the bloc over the subsequent years.

Then came Covid-19. Parts of Europe were especially badly affected, Italy in particular, heightening fears about the country’s finances. The EU’s initial response saw disagreement over how much support to provide to the worst hit countries, exacerbating concerns.

Why is there a disagreement over fiscal policy in the EU?

This disagreement hits at one of the central questions facing the EU: whether or not to pursue a closer fiscal union. That would mean having a centralised fiscal “capacity”, a fund or account, to which all members would contribute and have access to if needed. Capital could be raised by the issuance of euro area bonds and financial transfers could be made to countries if necessary.

A group of “frugal” members, namely Austria, Denmark, Finland, Netherlands and Sweden, have been reluctant. They tend to stress the need for financial discipline and worry they would end up bailing out more profligate members. It was these countries who were initially opposed to more generous support measures for countries like Italy in the Covid crisis.

But, July saw a significant break through: the announcement of Next Generation EU, a programme of economic stimulus initiatives, including a €750 billion Pandemic Recovery Fund.

Discover more from Schroders:

– Learn: Why the 21st century belongs to Asia

– Read: Is the vaccine the shot in the arm the market needs?

– Watch: How climate change could affect your investment returns?

Will the Pandemic Recovery Fund change the game?

The recovery fund, and the wider programme, marks a significant step. It will be financed by new issues of EU bonds and will provide direct, non-repayable transfers. The EU has issued bonds collectively before, but not on such a scale. Perhaps more importantly it will allow for direct transfers or grants to member states, which do not have to be repaid, as well as loans.

Some €390 billion is earmarked for grants to countries, to be allocated according to the severity of the Covid-19 impact, with €360 billion to be issued as loans.

This is a very positive political development. It affirms a unified, collective will to strengthen the EU, which has often been called into question, and should boost confidence in the region.

It is every bit as encouraging from an economic viewpoint. Its focus on investment to effect a transition to a green and more digitally-based economy has the potential to create millions of jobs. This too represents a decidedly forward-thinking move from the EU’s leaders with the aim of rebalancing the economy away from its reliance on manufacturing and exports.

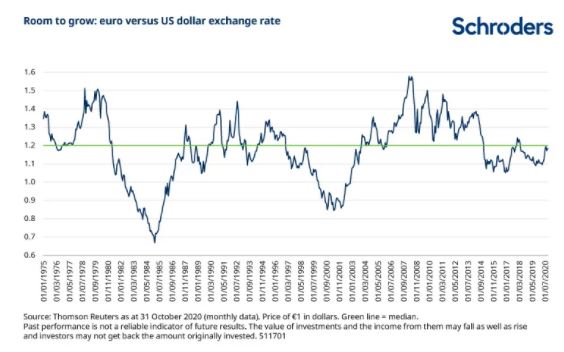

Why is this good for the euro?

Among other things, we see this as having longer-term implications for the global foreign exchange market, with the euro set to gain in strength and prominence, as the US dollar weakens. The dollar’s pre-eminent, “reserve” currency status could start to fade, for various reasons. With Europe’s policymakers’ pro-active approach to stimulating economic activity, the euro could, in turn, benefit, particularly if the US continued to struggle to implement economic stimulus.

If the increased confidence in the EU were to continue, it would strengthen the status of euro-denominated assets as low risk or safe haven. The dollar’s historical dominance has partly been due to its safe haven status.

When non-US investors turn to the safe haven of US government bonds or, as many have done in recent years, pour money into US tech stocks like Amazon, they need to obtain US dollars to do so. This boosts the currency. Higher growth in Europe, coupled with a more stable political situation, ought to have similarly positive effects for the euro over time.

Leading the way

Ultimately, the recent developments are positive. The recovery package is well-designed with a longer-term view, rather than looking for a short-term cyclical boost, and could be a template for other authorities to follow.

It may also be indicative of a deeper change, whereby the importance of monetary policy diminishes, and fiscal policy becomes more important as policymakers look to kick start growth.

Michael Lake, Fixed Income Investment Director at Schroders, said: “We remain constructive on the outlook for Europe, driven by the European Recovery Fund (ERF) and believe the market remains sceptical on the long run potential for structural improvements to growth.”

“We believe it to be a well-designed programme that will specifically target areas with high growth multipliers. Implementation will be a key variable, but we believe Europe is moving in the right direction in terms of boosting longer term growth. This should help reduce the dependence on extraordinary monetary policy.”

– For more visit Schroders insights and follow Schroders on twitter.

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.