‘Greedflation’ not to blame for UK price surge, former rate setter claims

“Greedflation” is not to blame for prices surging in the UK and instead businesses are pushing up prices in response to soaring costs, a former Bank of England rate-setter claimed today.

Michael Saunders, an ex-member of the monetary policy committee – the nine strong group that sets interest rates in Britain – and now senior economic adviser at consultancy Oxford Economics, has said isolated incidents of rising profits “do not reflect the overall picture” of the UK economy.

Speculation that companies have been exploiting the inflation crisis by unfairly lifting prices to beef-up profits, a process known as “greedflation,” has gathered momentum in recent weeks.

Supermarkets have been criticised for not passing on the reduction in commodity and transport costs as quickly as they raised prices after those costs soared.

Britain’s pricing watchdog the Competition and Markets Authority today announced it is probing food retailers and supermarket petrol forecourts to establish whether a “failure in competition is contributing to grocery prices being higher than they would be in a well-functioning market”.

The Liberal Democrats had called on regulators to examine supermarkets to establish whether they are unfairly heaping pain on shoppers to protect their margins.

However, Saunders rejected assertions supermarkets are participating in greedflaiton.

“The bulk of UK food price inflation reflects cost increases from the international surge in prices for agricultural commodities and energy,” he said in a note to clients today.

The cost of materials used by food manufacturers have jumped 29 per cent over the last two years, while consumer prices have leapt 29 per cent over the same period, he explained.

Similarly, oil and gas giants BP and Shell have come under intense scrutiny for pocketing huge windfalls from the increase in global energy prices after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In their latest accounts, the pair reported profits of £4bn and £7.6bn respectively, prompting calls from Labour and Lib Dems MPs for the government to amplify the windfall tax on the sector’s profits.

Profits at big energy companies have soared 170 per cent annually, according to data up to the third quarter of last year.

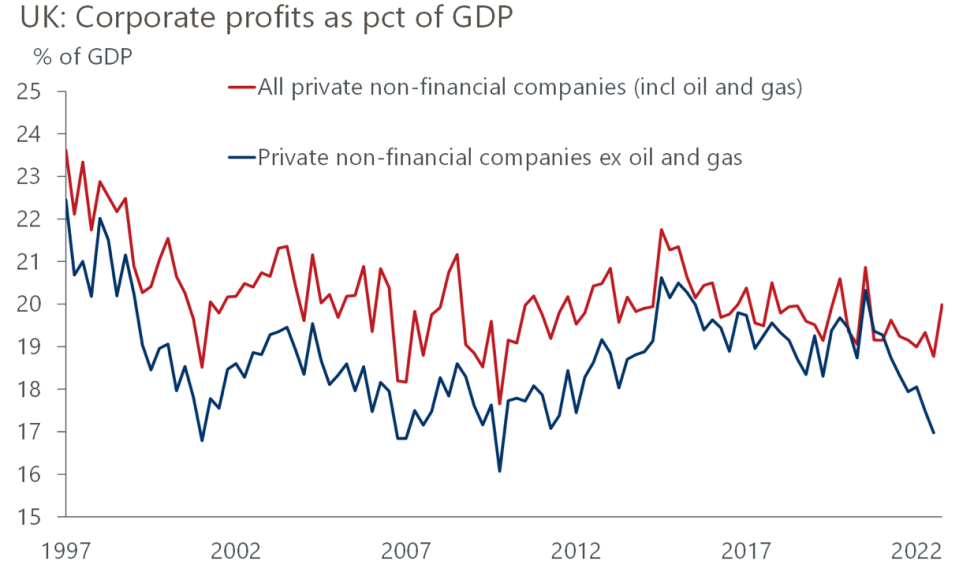

But Saunders said if their financials are excluded from the UK’s corporate margin estimates, it shows firms aren’t pumping up inflation to hoist profits.

“Take out oil and gas, where profits have risen sharply, and the share of company profits in GDP has fallen markedly” to their lowest level since 2009, Saunders said.

Saunders pointed out that if profiteering was widespread, then companies would “support [economic] activity, through increased spending on investment and employment, or through higher dividend payments and rising equity prices”.

“In turn, this would sustain job growth and eventually feed through to a recovery in real wages,” he added.

Instead, because both profits and families’ real incomes are being squeezed by inflation – a scenario that Saunders said more closely reflected the present dynamics in the UK economy – then firms’ margins would be trimmed as a result of a reduction in demand.

This would create “disinflationary pressures that will help bring inflation substantially lower,” he added.

Current MPC external member Catherine Mann said earlier this year she is concerned firms’ “strong pricing power” risks keeping inflation high. The European Central Bank has also signalled it is on the look out for companies launching excessive price rises.

It raised interest rates last Thursday for the twelfth straight time to 4.5 per cent, the highest level since October 2008.

The central bank in its new set of economic forecasts also said it has found little evidence of corporate profiteering, but that some firms whose input costs have dropped had not “automatically passed [those declines] through to consumer prices in an attempt to rebuild margins”.

Andrew Opie, director of food and sustainability at the British Retail Consortium, said: “When cost pressures facing retailers do eventually ease, retail prices will follow fast as they fiercely compete for market share.”

City A.M. has contacted BP and Shell.