Germany: EU’s largest economy faces ‘big deterioration’ – and risks slipping back into recession

The German economy is facing a “big deterioration” in the second half of the year, with the European Commission downgrading its forecasts for the bloc’s largest economy.

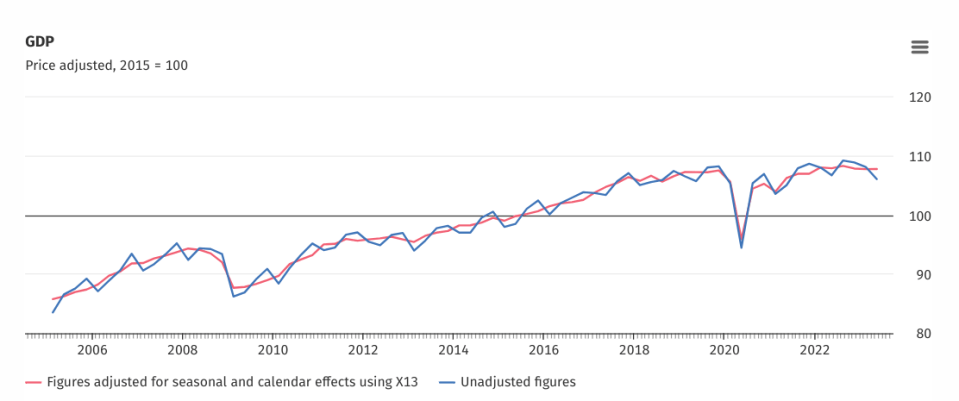

The German economy remained stagnant in the second quarter having sunk into a recession over the winter.

Whilst it’s not currently in recession, the Commission now expects the German economy to shrink 0.4 per cent in 2023, making it the only major European nation to do so – and it risks slipping back into it.

It was not long ago that Germany was driving growth in the bloc. Now it is being labelled the ‘sick man of Europe’. Where did it all go wrong?

Geopolitical challenges

Germany’s economic model has left it more vulnerable than many peers to changes in the geopolitical order. In particular, it has suffered from its reliance on Russian energy.

Before the Ukraine war, Germany around half of its gas from Russia and more than a third of its oil. Rising energy prices means its energy import bill is expected to grow over €124bn across this year and next, up from a combined €7bn for 2020 and 2021.

In notes accompanying its forecast, the commission said that in manufacturing, “the energy price shock following Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine hit particularly hard.”

It has since put in lots of work to diversifying its energy supplies but experts at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) said “it will take time for badly affected industries, such as the energy-intensive chemicals sector, to recover”.

Ties to China also pose challenges for Germany. The German economy is almost uniquely dependent on exports for a country of its size – with exports making up nearly 50 per cent of GDP – and China has been Germany’s largest trading partner for the last seven years in a row.

Attempts to decouple – or reduce critical dependencies, as Chancellor Olaf Sholz put it – will therefore hit Germany hard. Nevertheless, the government is determined to adapt its relationship with the world’s second largest economy.

Recently, the government laid out a strategy for its approach to China, saying “China has changed. As a result…we need to change our approach to China.”

In particular it highlighted pharmaceuticals and technology needed for semiconductors as areas where it needed to reduce its dependence on China.

Manufacturing malaise

Germany’s struggles to adapt to the changing geopolitical landscape reflect its unusual dependence on manufacturing.

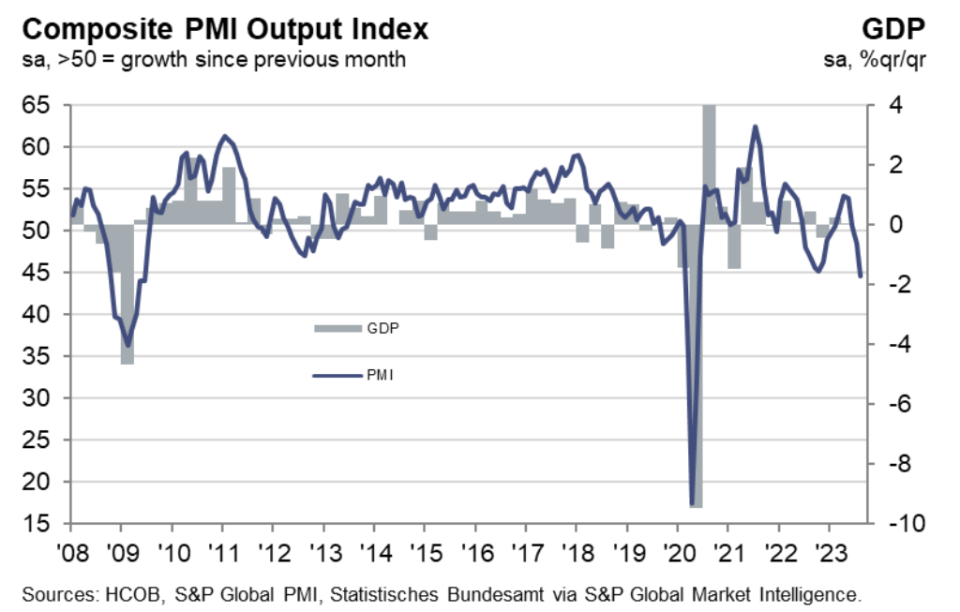

Over the past few years manufacturing – such as chemicals and car manufacturers – has been one of the principal engines of its growth. But in the most recent industrial production reading from July, production fell 0.8 per cent compared to the previous month.

This was the third consecutive fall and more than economists had predicted.

Franziska Palmas, senior Europe economist at Capital Economics, said there seems to be “no sign of a recovery in energy-intensive industry, with output still very close to its post-Ukraine war low.”

Many of Germany’s industries are struggling to adjust to the new reality, but the trend is most evident in the flagship car industry.

Experts at the EIU noted that the automotive sector is currently undergoing a “structural transition” as producers shift towards EVs. But Germany entered the market “comparatively late”, having predominantly focused on diesel vehicles.

This has enabled global competitors, such as China, to catch up while also taking a big lead on EV manufacturing. BYD, a Chinese company, has become China’s most popular car brand – the first time in 15 years a German car manufacturer was not China’s favourite.

What’s the government doing

The coalition government recently approved €32bn in corporate tax cuts in an attempt to boost flagging growth. The cuts are meant to incentivise climate-friendly investments and boost investment in R&D.

Chancellor Sholz meanwhile pledged to banish the “mildew of bureaucracy” as he called for a ‘Germany pact’ between the central government, federal states and local municipalities to energise the economy.

However, economists have not been impressed by the size of the intervention given the scale of the challenges.

Carsten Brzeski, global head of macro at ING, said the reforms will not be “a big game-changer for the German economy.” But Brzeski said it demonstrated the government was becoming increasingly aware of the challenges.

“It shows that the government has finally become aware of the economy’s problems. That being said, it will probably require more concrete steps in the same direction to get the economy up to speed again,” he continued.