Gen Z may love reading, but that won’t save the UK’s struggling libraries

Gen Z are making reading cool, but that won’t help the widespread crisis facing UK public libraries, writes Anna Moloney

Gen Z gets a lot of bad press, but there is one noble factor that is giving their reputation some reprieve – they love to read. Viral online phenomenon Booktok is one aspect of this, but, ironically, it’s the analogue aspect of reading that is most beguiling to the digitally native generation.

Indeed, while ebooks are certainly still a significant part of the publishing landscape, it’s print that’s in vogue. This has translated into the sales figures of publishing houses, many of whom have credited the growing Gen Z audience for a boost, while bookshop tycoon James Daunt, who stands at the helm of Waterstones, Barnes & Noble and Daunt Books, has cited the “hugely positive” influence of Booktok, which he said was reinforcing the reading of “real books”.

But filling the pockets of industry tycoons is not quite the idyll imagined by these romantically-minded literarians, which helps explain why many of them are instead flashing around a new dernier cri: the library card.

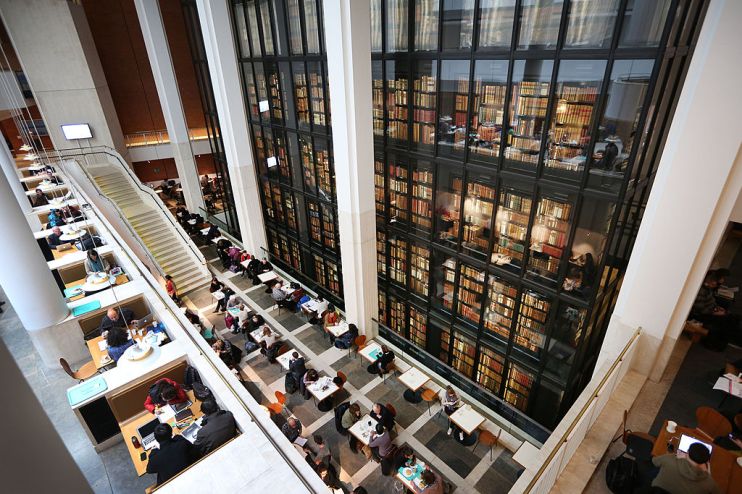

Take Henry Earls, a Booktokker whose videos have racked up over 19m views, who posts clips of himself languishing around the New York Public Library, complete with musings on the plight of the hopeless romantic and clad in knitwear that whispers I was born in the wrong generation. Concurrently, the rise in popularity of the ‘dark academia’ aesthetic (think brown leather satchels and grand, moody interiors) betrays a yearning for a romanticised pre-digital age. It’s not just reading, but the aesthetics of reading, that have captured this generation.

That may be all very well for the Beaux-Arts-loving bibliophiles of New York, but what about closer to home? Truth be told, the image most of us have of our local council-funded public library, perhaps overrun with children or severely underfunded, is not quite as alluring.

Nick Poole, CEO of industry body the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP), said the last decade has seen the UK’s public library network “hollowed out”, with local councils often left with little choice but to cut library services in a near-impossible task of balancing the books. Independent libraries seem to be struggling too, with the Bishopsgate Institute recently forced to close its beloved reading room on Liverpool Street, previously open for free to the public, due to financial pressures.

As a result of such pressures, many of the things that make libraries so valued have to be sacrificed: opening hours are reduced, the professional expertise of librarians is replaced with volunteers and, perhaps most devastating for our Gen Z aesthetes, beautiful buildings must be sold. In Norfolk, for example, recent news over the relocation of the King’s Lynn central library from its Gothic-style red-brick home to a former Argos in the city centre – where surely no self-respecting Gen Z intellectual would be caught dead – has caused public outcry.

Voices from the library sector are unified in their demands: they want long-term funding agreements so they can stop making short-sighted decisions. Selling property may be a quick fix, but the consequences of such decisions will ultimately catch up with them.

Despite this, there is evidence that younger audiences are indeed increasingly engaging with the library. Data from 2017 found that 15-24 year-olds were the top users of libraries across all age demographics, while Libraries Connected representative James Gray said its members had noticed growing demand for its young adult novels. The rise in remote working has also seen an increased use of libraries as workspaces.

Libraries have also been exemplary in tailoring their services to changes in demand; as Poole put it, they function as “rooms of requirement on the high street”. Many now host pharmacies, warm hubs, social groups, yoga courses and business centres, the value of which is hard to quantify. Analysis from the University of East Anglia put the value generated by libraries, accounting for things like their impact on health and education, at £3.4bn a year. Meanwhile, 12,288 businesses have been launched through the help of library business centres, 96 per cent of which were still trading after four years (outlasting the UK startup failure rate of 60 per cent).

The online perks attached to having a library card are also plentiful – and incredibly undermarketed. By signing up for an online membership to your local library, for example, you will immediately gain access to thousands of ebooks and audiobooks, as well as newspapers and magazines that you might otherwise be forking out hundreds of pounds for, in what feels like an almost illicit secret of the trade. And this is part of the problem – many of us are simply unaware of all the services public libraries offer. Incredibly, there are more libraries than McDonalds in the UK (in fact more than double), but most of us are probably more familiar with the quickest route to a McFlurry than how to check a book out.

But there is only so far innovation can go. Poole told me the impact of a long-time mantra of the sector “use it or lose it” was fading, with evidence showing libraries are being lost regardless of demand. Gen Z’s reading buzz and yearning for that elusive ‘third space’ may therefore boost membership, but public libraries need urgent action, and proper recognition of the public service they offer, to save them.