Frank Stephenson on the rights and wrongs of car design

Frank Stephenson makes even an introductory Zoom chat feel like a long-awaited reunion. Lucid and professional, yet brimming with endless anecdotes (many of which I can’t print here), the 61-year-old car designer is an ideal interviewee. As viewers of his YouTube channel will know, he also doesn’t shy from strong opinion.

Starting with the spoiler on the Ford Escort RS Cosworth, Frank’s design CV includes the BMW X5, modern Mini and Fiat 500, McLaren P1 and many more.

Here, he talks about his career so far, what inspires him and some of his favourite cars. And he explains where BMW design has gone “wrong, wrong, wrong…”

Tell us about your childhood. You were very well-travelled…

I grew up in Casablanca, Morocco, with my American father and Spanish mother. That sounds exotic to some people, but it was just normal for me. Horses and donkeys were far more important than cars. I attended an English-speaking school from the age of six, then we moved to Istanbul, Turkey, when I was 11.

We relocated again to Madrid, Spain, for my last year of high school, when I started racing motorcycles. I won the Spanish motocross championship twice, then joined a factory team. It was lots of fun, but I wasn’t making enough money to leave home. So, at the age of 22, I applied to university in California to study car design.

The course took four gruelling years, working seven days a week with no social life. It was like a marathon; the moment you stopped, you lost momentum. But when I graduated, I was ready to hit the ground running.

What made you decide to become a car designer?

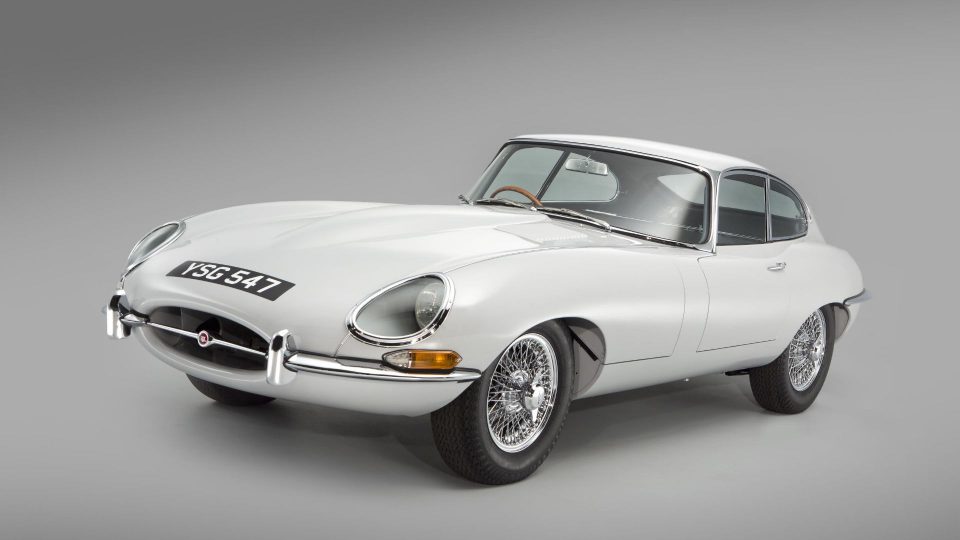

One single moment that changed my life forever. On the 19th of March 1969, I was walking hand-in-hand with my father through Casablanca when we saw a Jaguar E-Type. It was an early Fixed Head Coupe, and I was transfixed. My father had to drag me away.

That car still has an emotional impact for me today. Some people are transported by smells or listening to music; for me it’s all visual. I see an E-Type and I’m back in Morocco in a flash.

You began your career at Ford, designing the spoiler for the Escort RS Cosworth. Quite the calling card…

That was the first project I got my teeth into. Ford had approached me during my university course, so I already had a job lined up. I moved to Cologne, which was in West Germany at the time, and started work in the wind tunnel.

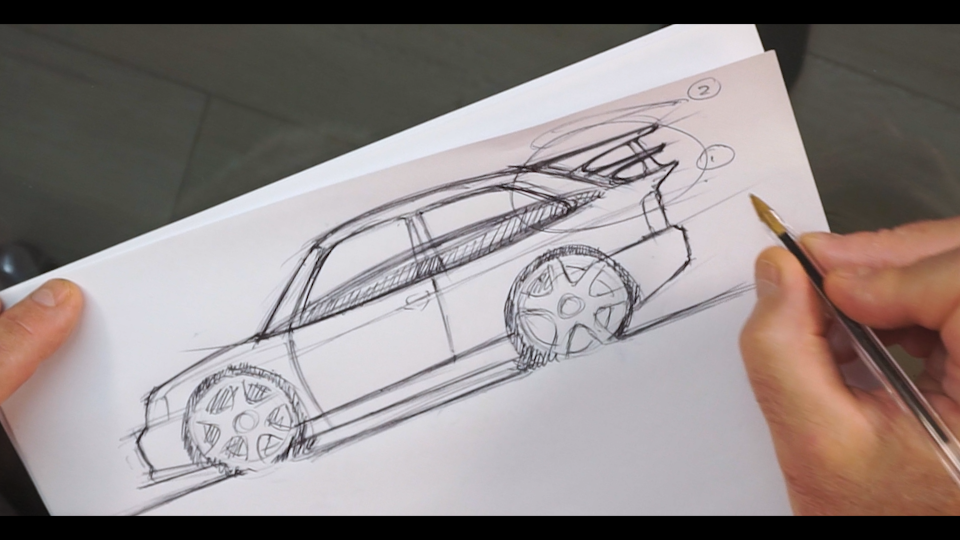

The Cosworth was unusual because it used an Escort body on the platform of another car [the Sierra RS Cosworth 4×4]. It needed lots of rear downforce for racing, and this was before the age of diffusers on production cars. But I had the freedom to think outside the box.

Inspired by the Red Baron and his Fokker DR.1 tri-wing plane, I designed a triple-layer spoiler. It looked crazy and worked brilliantly in terms of aerodynamics. You couldn’t see much out of the back window, but that wasn’t the point. The three-tier wing could have become iconic, but it fell victim to Ford cost-cutting.

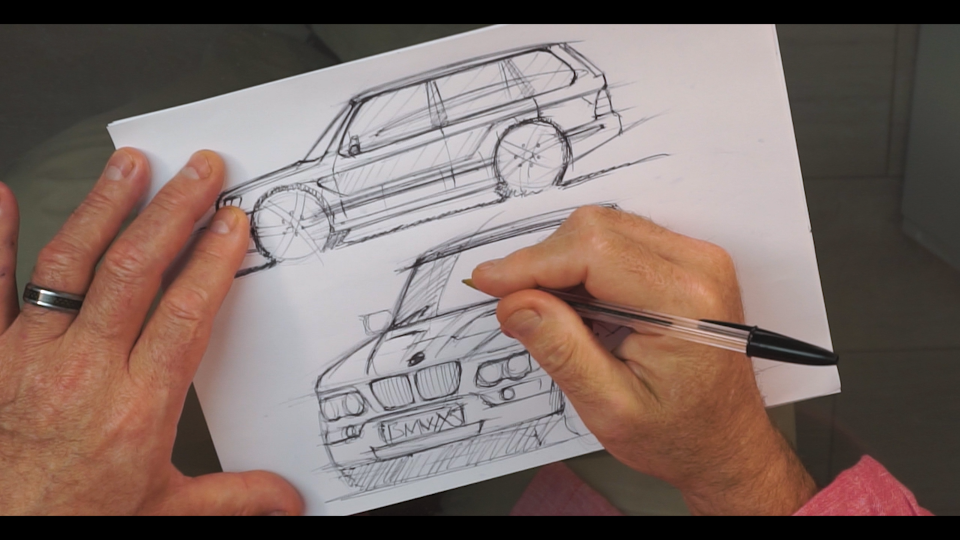

You then moved to BMW and designed the original X5. Did you foresee how SUVs would transform the car market?

I don’t think anyone knew what effect the X5 would have. BMW called it an SAV – a ‘Sports Activity Vehicle’ – because it reinvented the SUV as we knew it.

The brief was to design a BMW based on the Land Rover [Range Rover L322] platform that could be used for anything, from the school run to visiting the opera. It combined the sportiness BMW was known for with the comfort of a 7 Series, plus off-road ability that wasn’t far off a Land Rover.

Female drivers in particular loved the ‘command driving position’, which was up high for great visibility. What started as a niche quickly became mainstream. The X5 really opened up the market.

Was it hard seeing Chris Bangle rip up the rulebook after you at BMW?

I remember Chris Bangle walking into the design studio in 1993, dressed in a neon blue suit and cowboy boots. He just yelled: “Hey guys, how y’all doing? I’m your new boss!”. We asked him if he’d ever designed anything and he mentioned a car coming soon called the Fiat Coupe. Nobody knew who he was at the time.

Chris wanted to take BMW design in a different direction, although his ideas kept being shot down at first. It was only when Dr Pischetsrieder took over as chairman that the ‘flame surfacing’ revolution began. I was actually more focused on the Mini project at that point.

Domagoj Dukec, BMW’s current head of design, says shock-value is more important than beauty. What’s your take?

That sounds like a good excuse for a bad design. The new 4 Series has shocked alright, but this is shock for its own sake. BMWs are about understated elegance.

You have to consider what a car is meant to do. In a ‘haute couture’ hypercar, shock is a valid reaction, but not for a 4 Series. I’ve heard it was designed that way for the Chinese market. So why do the rest of us have to suffer?

Just slapping a licence plate across the front like a band-aid… how much less refined can a BMW be? It completely turns me off. I find it hard to believe that somebody stood back and said: “Yep, let’s build it”. Were they in a beer garden at the time?

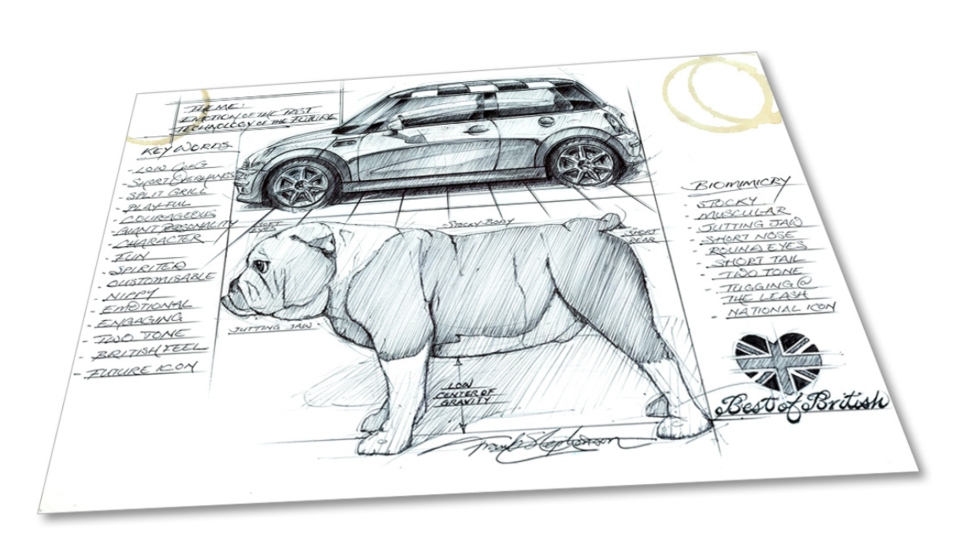

Two of your most celebrated designs are the Mini of 2000 and Fiat 500 of 2007. How do you reimagine an icon?

The Mini took a long time, but was one of the most interesting projects I’ve worked on. BMW was determined to get it right. The key objective was to handle it like a British brand, not a German one. It needed to be classless and almost timeless, like the 1959 original.

We had less than a year to design and launch the 500 – its mission was to turn around the company. Fortunately, Fiat had this loveable icon in its past, and it still existed in Italian minds as part of their heritage. We capitalised on the evolutionary approach taken with the Mini, then offered plenty of customisation on top. It still looks as fresh today.

You joined McLaren in 2008 and helped shape the brand from scratch. Was that challenging – or liberating?

It was both. I could do anything, but what I did had to be right. A Ferrari has to look like a Ferrari, right? The MP4-12C didn’t need to look like a McLaren.

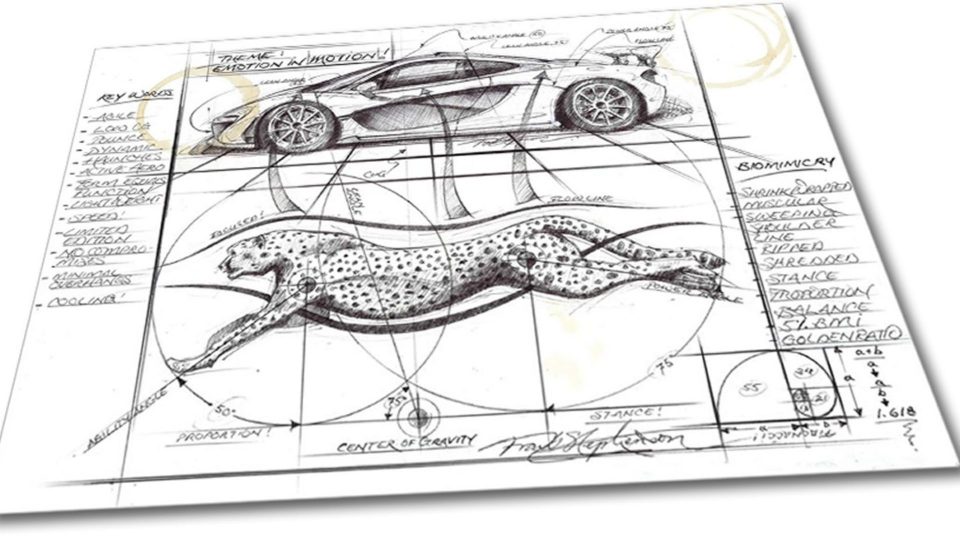

Having been a Formula One constructor, McLaren wasn’t known for making beautiful cars. I took a ‘fit for purpose’ approach to the design, shrink-wrapping the skin around the components like an F1 car, for minimum visual mass. It created a design language for the brand.

What’s easier to design, a supermini or a supercar?

It’s doesn’t matter what kind of car you’re designing, the challenge is to make it emotionally and immediately desirable. Nobody has to buy your product, after all: there are enough choices on the market. So if you want your car to be ‘The One’, it needs to be love at first sight.

You need to be conscious of cost, of course. But ultimately you want to make each detail as good as possible – let somebody else put a price on it. That’s not the designer’s job.

What are your three favourite car designs ever?

I’ll go for three cars from three different eras. From the Art Deco period, the Talbot-Lago T150-C SS Teardrop Coupe. It’s one of the most beautiful cars in history – just gorgeous. Then from the 1960s, when car designers were true artists and sculptors, I’ll choose the Alfa Romeo 33 Stradale. It has a lot of innovation in the glass area. And it’s tight, tiny and perfectly proportioned.

Finally, from the modern age, one of my own: the McLaren P1. We weren’t sure about the design at first, but it still looks good in the wild.

What is your daily-driver, and do you own any of the cars you designed?

My wife owns a Fiat 500 cabriolet, but I have a Land Rover Freelander [which Frank didn’t design]. It’s like an old pair of blue jeans – I just throw the dogs in the back and don’t worry about getting it dirty.

For fun, I’ve got a Ducati – a highly modified 1198S with a carbon rear spring, aero wings and everything replaced. Much as I love cars, I feel more awake and alive on a motorcycle.