Food prices set to rise ‘across the board’ as inflation fears build

Food prices surged at their fastest pace in nine months in January and will “rise across the board” this year, a new survey has suggested, raising concerns about the potential resurgence of inflation this year.

The British Retail Consortium’s (BRC) shop price index showed that food prices rose 0.5 per cent month-on-month, up from 0.1 per cent in December.

“This month’s figures showed early signs of what is to come,” said Helen Dickinson, chief executive of the BRC, noting that ‘ambient’ food prices rose one per cent on the back of a spike in sugary products, chocolate and alcohol.

Recent forecasts from the lobby group suggest that food prices will rise by an average of 4.2 per cent in the second half of this year as firms deal with £7bn in extra costs announced in the Budget.

“Higher employer NICs, increased National Living Wage, and a new packaging levy mean that prices are expected to rise across the board,” Dickinson said.

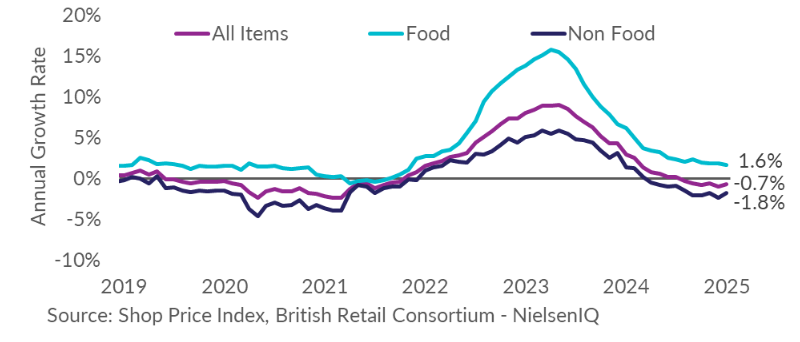

Nevertheless, annual food inflation still eased to 1.6 per cent in January, down from 1.8 per cent previously and at the lowest level since November 2021.

Non-food prices also remained in deflation thanks to the January sales, meaning shop prices generally fell by 0.7 per cent in the year-to-January.

Mike Watkins, head of retailer and business insight at NielsenIQ, said that consumers were still being careful with their money, so firms may find it difficult to pass on higher costs.

“Shoppers continue to be unsure about spending and many are seeing a continued squeeze on their household incomes. So we expect non-food retailers to still promote and food retailers to still offer price cuts over the next few weeks,” he said.

The survey indicates the competing dynamics in the economy which will determine the direction of inflation in the months ahead.

There are a range of cost pressures facing the economy, beyond the measures announced in the Budget. These include higher energy prices, a weaker pound and resilient wage growth.

Last week’s PMI showed that input prices facing businesses were rising at the fastest pace in over one-and-a-half years. Many economists anticipate that inflation could rise to over three per cent by the spring on the basis of these pressures.

But it is less clear whether these costs pressures will transfer into persistent inflation, or whether they end up being temporary.

A number of economists have argued that demand in the economy is too weak for firms to pass on higher costs without putting off customers from buying their products. This could keep a lid on inflation in the medium term.

Alex Kerr, UK economist at Capital Economics, suggested that the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, which sets interest rates, would put more weight on the weakness in demand rather than rising costs pressures.

“The MPC are increasingly likely to conclude that the weakness of economic demand will eventually weigh on inflation,” he said.