Floating cities or climate visas: Is this the choice for environmental migrants?

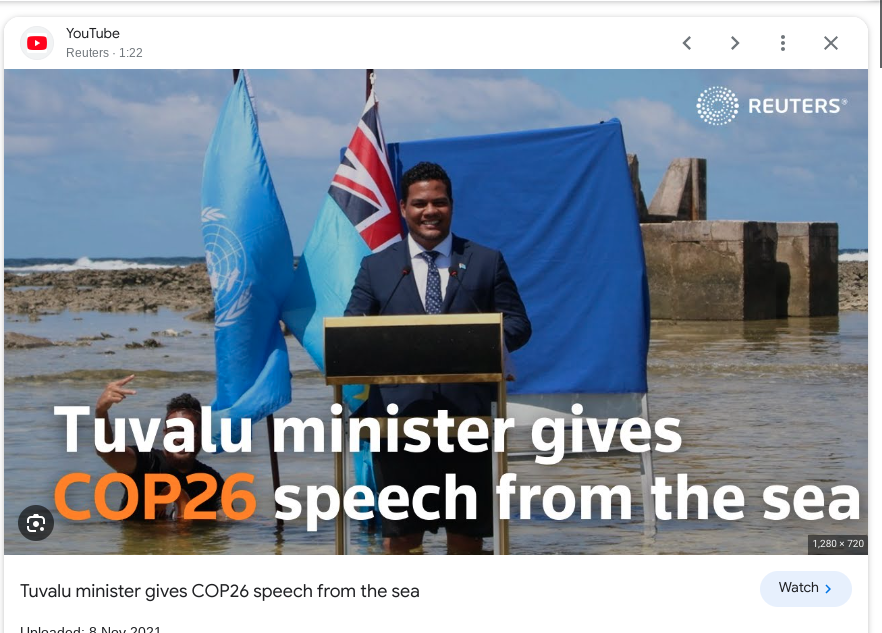

You’ll remember the image: Tovalu’s climate minister Simon Kofe rolling up his trousers to give up a recorded speech for the Glasgow Cop26 climate conference standing knee-deep in seawater symbolising his nation’s vulnerability to the climate crisis in an appeal for help.

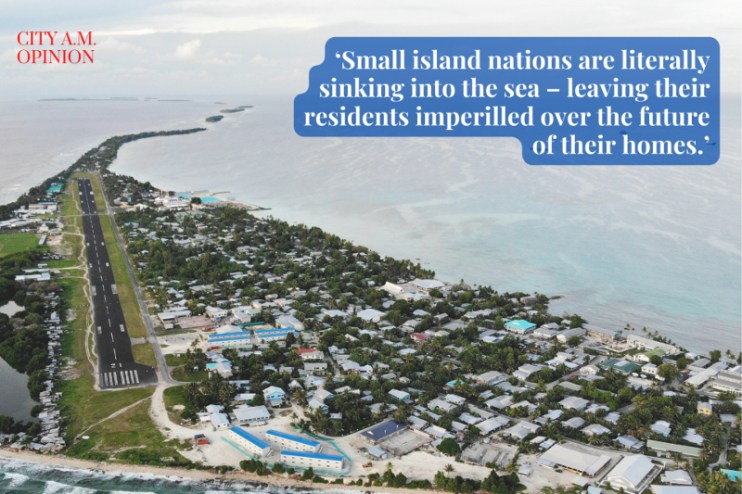

These nations are literally sinking into the sea – leaving their residents imperilled over the future of their homes.

But it’s not just small island states – the climate crisis could force over 1bn people from their homes by 2050. Some 150m p ople are currently living on land that will be below the high-tide line by 2050. The United Nations estimates extreme weather is causing over 20m people to have to move out of their homes to new areas each year – in an unprecedented wave of migration that will only get worse.

In the UK the politics of immigration is fraught to say the least. Whilst Brexit was presented as an opportunity to cut back on immigration from the EU, numbers have actually gone up since the referendum and immigration remains at the top of voters’ list of worries.

This is especially so with the ‘Stop the Boats’ slogan flaunted by the Conservative Party, which though controversial addressed a real issue. There were 46,000 people detected arriving in Britain from across the Channel last year, making journeys that endanger their lives.

The scheme designed to prevent this – offshore processing in Rwanda – is subject to a decision in the Supreme Court due next week.

So the argument goes, if we will wind up with thousands of people fleeing as a result of climate change, better to be proactive and offer specific visas so we can have control over who comes in.

But this isn’t actually what the people of these countries necessarily want from Western nations.

New Zealand was the first country to float the idea of climate refugee visas back in 2017 under Jacinda Ardern. However, after consultation over six months the plans were dropped – as Pacific islanders did not actually want refugee status.

Instead, they preferred an approach of reducing emissions, supporting adaptation efforts and providing legal migration pathways.

In the light of news that Australia is now setting up a special new visa to citizens of Tuvalu offering citizens an escape from rising sea levels in the low-lying Pacific island nation, City A.M. wondered: are these visas a good idea? Or is innovative infrastructure – like floating cities – more appealing?

Climate visas

Australia’s proposal is that every year up to 280 people will be given permanent residency – amounting to 2.5 per cent of the population (11,000).

Leaving aside the politics of Australia’s decision (China is also vying for ties with Pacific island countries and Australia is conscious of rebranding from its poor record on climate).

Models suggest for every degree of temperature rise, 1bn people will be displaced and analysts are warning of a mass migration from affected countries to northern ones, such as the UK.

Preparing legal routes of entry could prevent illegal immigration spikes and prepare the UK, and affected people, for the population change.

Centre right think tank Onward already published a report urging the UK government to input “new controllable visa schemes” earlier this year.

The proposed natural disaster visa scheme would permit people to either earn money and rebuild their lives before returning to their home country or to settle permanently in the UK if they had no home to return to.

Alex Luke, senior researcher and co-author of the report, said: “The two controllable visa schemes would demonstrate firm global leadership, boost resilience abroad, and even help us to meet our own energy security and net zero targets.

“It is entirely in keeping with the recent Illegal Migration Bill and the refreshed Integrated Review.”

The problem with this approach is that it risks the loss of culture and community, history and heritage, that is intertwined with place.

Floating islands et al

The alternative is building climate adaptation infrastructure. For example the African island nation Sao Tome and Principe which was experiencing coastal flooding 10 times a year, the World Bank worked to boost flood resilience through sea walls and rock revetments, while working with communities on voluntary relocation to safer areas.

After the 2004 tsunami, the Maldives built heightened sea defences, elevated buildings and early warning systems. The island nation also explored replacing diesel fuel with solar power and determining how to safeguard precious fresh water supplies.

One more memorable suggestion is the idea of building floating islands on top of or adjacent to small island states as an alternative, indestructible base near the existing community.

In 2018 a startup building floating man-made islands as a climate crisis solution held discussions with French Polynesia to build a prototype in their territory. However after protests and government opposition it got cancelled.

This is probably because the proposed island was set to be a “libertarian utopia”, funded by Silicon Valley contrarian Paypal founder Peter Thiel.

In the Maldives, the floating city idea has proved buoyant. The island nation is developing a floating city to house 20,000 people in a lagoon in the Indian Ocean, near the capital. The city will be built on a series of hexagonal-shaped floating structures and should rise along with sea levels.

The Maldives is currently predicted to become uninhabitable by 2100 due to rising sea levels.

The global conversation will inevitably turn to the fate of small island state dwellers. Whether the answer is climate visas or new floating cities – and most likely it will be a combination of policies that provide citizens options for their future – there is not much time to play with.

In the unique archipelago of Tovalu some 40 per cent of the capital district is underwater at high tide and by the end of the century the country is projected to be fully submerged. Two islands out of the nine atolls are already nearly submerged. The island is mostly just around three metres above sea level. It is also very narrow. Locals say their home is being “swallowed” up.