Financing growth? How the City’s frailties have hamstrung productivity

The single biggest economic question facing this government is how to improve the UK’s sluggish rate of productivity growth.

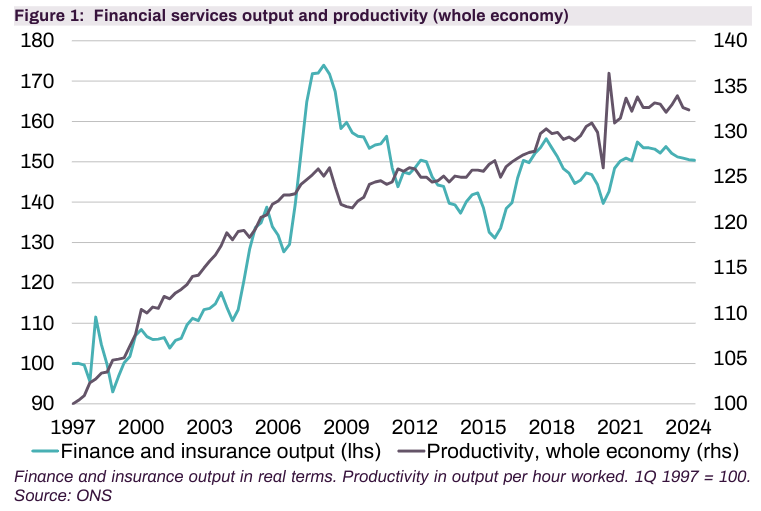

Since the financial crisis, productivity growth in the UK has slowed significantly from its pre-2008 trend. Sluggish productivity growth has translated into much slower economic growth and stagnant living standards, not a happy combination.

Nobody is quite sure why productivity growth has ground to a standstill. Entire libraries have been written trying to uncover the reasons for the slowdown, a question that has become known as the ‘productivity puzzle’.

In a note last week, Kallum Pickering, chief economist at investment bank Peel Hunt, suggested that one area that has not received enough attention is the contribution of the financial sector.

In brief, a large and liquid financial system should ensure high-growth industries get the capital they need, helping to fund investment and facilitate the expansion of the most dynamic and innovative firms.

As Pickering said: “The financial sector serves as a nervous system, helping to efficiently coordinate the whole economic body. When the financial system stops growing, it acts like a straitjacket on the broader economy”.

Pickering pointed out that there is a visible correlation between the slowdown in productivity growth and the stagnation in financial services output post-2008.

Still, despite the post-crisis slowdown, London remains one of the world’s premier financial centres, so surely this should be an area where the UK outperforms? Well not exactly.

There’s no doubting that the UK’s financial system is extremely good in a number of areas – asset management and derivatives trading stand out as two particular highlights – but that does not necessarily make it all that effective in those areas which do most to drive productivity growth.

Pickering identified London’s struggling equity markets as a prime example. He argued an “overly precautionary” approach to regulation has forced pension funds out of the equity market, making it more difficult for domestic companies to grow.

Over the past 25 years the proportion of assets that UK pension funds allocate to UK equities has fallen to 4.4 per cent from over half.

“This neglected part of the domestic market deserves serious policy attention, especially as it may play a critical role in solving productivity weakness,” Pickering argued.

Another noticeable weakness is the depth of capital markets outside of London and the south east.

Striking research from the Productivity Institute suggests that the gap in risk premia between London and the UK’s economically weaker regional economies is around 250–300 basis points.

That’s roughly equivalent to the spread on sovereign bonds between the UK and Romania.

Credit spreads reflect the perceived riskiness of lending so the Productivity Institute’s research effectively suggests that lenders perceive the rest of the UK as being part of a different country to London and the south east.

No doubt many business leaders outside the south east will have experienced the challenges of accessing finance. It does not reflect well on the breadth of the UK’s financial system or the long-term prospects of the economy.

Lending to small businesses is another area where the UK’s financial system has traditionally struggled, likely at least in part because of the regional concentration of the financial sector.

This problem seems to have been getting worse. According to the Impact Investing Institute, the success rate for SME applications for bank loans fell from 80 per cent in 2018 to only 50 per cent in 2023.

SMEs have increasingly looked elsewhere for finance. According to the British Business Bank, 59 per cent of small business lending came from outside the big banks last year, but the sector is still relatively underdeveloped.

Championing the UK’s financial system should not obscure the fact that there is plenty of room for improvement.