Film review: Selma depicts a pivotal moment in Martin Luther King’s life

Cert 15 | ★★★★☆

Selma does what Lincoln did so successfully and what Long Walk to Freedom made the mistake of not doing – instead of compressing a great life into two small hours, Ava DuVernay’s Martin Luther King biopic depicts a pivotal fragment of that life, one in which the greatness of the whole is distilled.

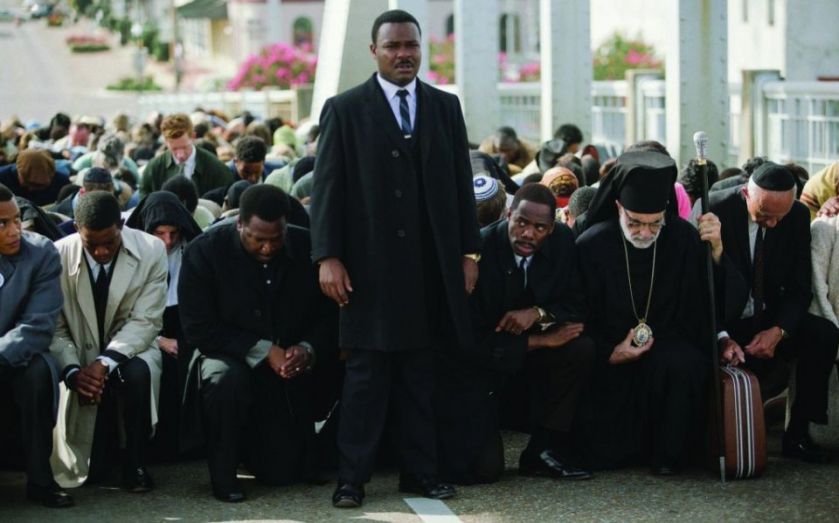

That fragment is the six months or so leading up to the peace march from Selma to Montgomery. King (played by David Oyelowo) had won the Nobel Prize. To a large extent the moral argument had been won, and it was now a question of dismantling the racist bureaucratic obstacles put in place to prevent black people from exercising the civil rights they fought so hard to obtain.

To do so required inspiring leadership, but it also required political guile. In another parallel with Lincoln, DuVernay and Oyelowo show us the twinkly-eyed pragmatism of a man held up as a saint. We get a sense of the canniness that whittled King’s moral velocity to a sharp, efficacious point – for non-violence wasn’t just a moral principle, but a supremely effective tactic, and one that King arrived at through political intuition as much as religious faith.

The scenes in which he wrangles with a preoccupied Lyndon B Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) do a better job of humanising King than the rushed family scenes with Coretta King (Carmen Ejogo). Another problem is the orangey-gold sheen. There’s a leather-bound, sanitised feel that obsequiously courts recognition from the Academy, recognition that, in the end, was not forthcoming.

Astonishingly, Oyelowo didn’t receive a nomination for Best Actor. He doesn’t only achieve a likeness, he achieves a spiritual union with Dr King that allows him to simultaneously encompass his goodness, his flaws and his towering charisma. That the Academy and Bafta both failed to recognise him is a disgrace, and perhaps another reminder – in a year full of them – that while the black community has come a long way, it has far from overcome.